The two-seater biplane had been roaring above Santa Monica for about twenty minutes, executing a series of graceful loops against a cloudless sky. Motorists fleeing the stifling heat of Los Angeles on 1923’s Fourth of July holiday pulled over to watch from the side of the main highway to Venice and Ocean Beach. Thousands of people, it was later estimated, stopped what they were doing and looked up.

Venice residents would have recognized the plane preforming the impromptu airshow. It was The Wasp and at the controls was B.H. DeLay, “one of the best known aviators in Southern California,” as the Venice Evening Vanguard described him. He operated the airfield in the resort town, owned a small fleet of passenger planes, and staged aerial stunts in Hollywood movies. No holiday or special event was complete until DeLay swooped over Venice’s beaches and amusement parks to dazzle the crowds with his daredevil performances.

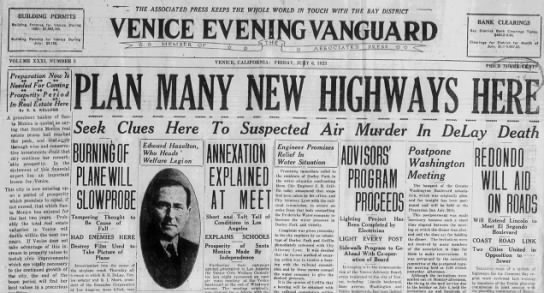

The Venice, California daily paper was the first to publish allegations that aviators B.H. DeLay and R.I. Short were murdered. (Venice Evening Vanguard, July 6, 1923)

The Venice, California daily paper was the first to publish allegations that aviators B.H. DeLay and R.I. Short were murdered. (Venice Evening Vanguard, July 6, 1923)

The Wasp was at an altitude of about two thousand feet when its wings suddenly collapsed. “Both wings of the plane bent back,” by one account, “as though on hinges.” Another report described them as “snapping like reeds.” The plane went into a freefall, dropping “like a wounded bird” and plummeting to the ground at high speed. Other fliers watching from Santa Monica’s Clover Field, about a mile away, jumped into cars and raced to the scene. The plane was a shattered mass of wood and metal. Thirty-one-year-old DeLay, the father of two young daughters, and his passenger, Los Angeles businessman R.I. Short, were dead. Their fellow pilots managed to remove the bodies – both “mutilated almost beyond recognition,” the Los Angeles Times told its readers – before the wreckage burst into flames.

Flying was a risky business. It was just two decades after the pioneering Wright Brothers designed and flew the world’s first manned, self-propelled aircraft. Planes were rickety by today’s standards; wings and fuselages were framed in wood and covered in fabric, and most had open cockpits that exposed pilots to wind and weather. The newspapers of the day were filled with reports of fatal crashes due to mechanical failures, pilot error, and bad weather or poor visibility. Commercial air travel was in its infancy but at least three airliners crashed that year, killing a dozen passengers and crew. Stunt pilots and fliers trying to set new distance records died at an alarming rate. “So long as the dangers of air travel are as great as they now are and the accidents as numerous,” scoffed an editorial in Muncie, Indiana’s Evening Press in 1923, “we must conclude that air navigation still is in the experimental stage.”

___________________________________

This story originally appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

___________________________________

DeLay himself had survived crashes and close calls. He was a skilled and experienced pilot who had been flying for a decade. For all his stunts and daredevil feats, he had a reputation as a careful, safety-conscious airman. “A man of his knowledge of the flying game,” the Venice newspaper noted, “would not be likely to endanger his life with a faulty plane.” Was the crash an accident, or was there a more sinister explanation for the catastrophic structural failure that sent the Wasp into a nose dive? DeLay’s friends suspected someone had tampered with his plane. Not long before, on a night when DeLay was at Clover Field, someone had fired a shot at him. “Had Enemies Here,” the Venice newspaper noted in the wake of the crash.

The rumors of foul play soon caught the attention of the editors of a new weekly magazine that had hit newsstands four months earlier. Time offered a brief account of the crash under the eye-catching headline, “Modern Murder.” DeLay, the magazine mused, may have been the victim of a new form of homicide “more subtle than mediaeval poison … the first airplane murder.”

* * *

Beverly Homer DeLay was the son of a wealthy mine owner and seemed bound to follow in his father’s footsteps. Born near San Francisco in 1891, he studied mine engineering and managed an Arizona gold mine before he discovered his real passion: speed. He graduated from racing cars to flying. By 1919 he was competing in long-distance races, including a multi-leg flight from Los Angeles to Phoenix, and taking thrill-seeking celebrities and tourists on flights over Santa Monica Bay. Soon he was in charge of the Venice airfield and operating five planes, including a six-passenger aircraft that was the largest in service on the West Coast.

Reports that DeLay was the victim of the “first aerial murder” appeared in newspapers across America. (Muncie Evening Press, July 17, 1923)

Reports that DeLay was the victim of the “first aerial murder” appeared in newspapers across America. (Muncie Evening Press, July 17, 1923)

Motion picture stunt work for Fox, Warner Brothers, Vitagraph and other studios became a lucrative sideline. DeLay and his planes appeared in dozens of Hollywood movies between 1919 and 1922, sometimes performing feats never before captured on film. He swooped down from the sky to pluck stunt men from buildings, from moving automobiles, motorcycles, boats, and trains, and even from horseback. He earned the distinction of being the first pilot to use his plane to knock down a movie-set building.

DeLay became a fixture in the sky over Venice. Promoters hired him to buzz the beaches and drop advertising leaflets and free theatre passes to the bathers below. He performed dives, barrel-rolls, tail spins, and loop-the-loops for the crowds attending exhibitions and holiday events. For one stunt, he flew overhead with a man dangling below his craft on a rope ladder. He teamed up with other pilots to stage mock dogfights, setting off fireworks and smoke bombs to simulate explosions and gunfire. He installed lights to illuminate his plane so he could entertain spectators during nighttime events.

Some stunts did not go so smoothly. During Christmas celebrations in 1920 he was enlisted as a “modern Santa Claus,” but his attempt to land on Venice Beach to distribute presents went awry when a large wave struck his plane as it taxied and almost dragged the machine into the sea. DeLay and his passenger escaped unhurt, but the plane’s propeller was broken. Another flight almost ended in disaster. A gust of wind buffeted his plane as he was landing and sent it into a nosedive. DeLay, who was badly bruised and suffered a concussion in the crash, was lucky to have survived.

He earned praise in March 1921 when he skimmed over the ocean in a futile attempt to locate a drowning man. Within days he had established a life-saving station at the airfield, equipped with buoys he could drop to aid other swimmers in distress. But not all his deeds were as civic-minded. He wielded enormous power in local aviation circles, and rubbed some people the wrong way. He slashed the price of a plane ride by half, to five dollars, forcing his competitors to follow suit. Venice appointed him its inspector of aircraft, and no plane could be operated in the city until it had passed his inspection. He even scolded homeowners to repair or replace their roofs, to ensure they would “look nice” when viewed from airplanes passing overhead.

In the summer of 1921 DeLay announced bold plans to make Venice “the center of commercial aviation in California.” The B.H. DeLay Aircraft Company issued $100,000 worth of shares to finance a major expansion that included buying more planes and establishing new passenger routes. DeLay had the exclusive rights to fly to Catalina Island and was about to launch regular service to San Diego, San Bernardino, San Francisco and other centers. And he had deals with two hotel chains to take their wealthy guests aloft for aerial tours. DeLay could barely contain his enthusiasm for the future of the industry, as well as his airfield and his company. “The general public does not appreciate the rapid growth of the enterprise,” he told a journalist. “If it did there would be a mad scramble to capture this field.”

There soon was.

* * *

A fight for control of commercial aviation in Venice broke out in September 1921, two months after DeLay bragged about the bright future in store for the local aviation industry. Four fence posts were driven into the turf at his airfield, making it impossible for planes to take off. After DeLay had them uprooted, a man named C.E. Frey showed up with a group of men who began to dig a trench across the runway. Frey claimed he had purchased the property and had the right to evict DeLay and his company. DeLay’s father, a director of the aviation company, filed criminal charges of disturbing the peace against four of Frey’s associates – pilots who were storing their planes at the airfield. Frey responded by charging the DeLays, their lawyer Francis Heney and two of their employees with the same offence.

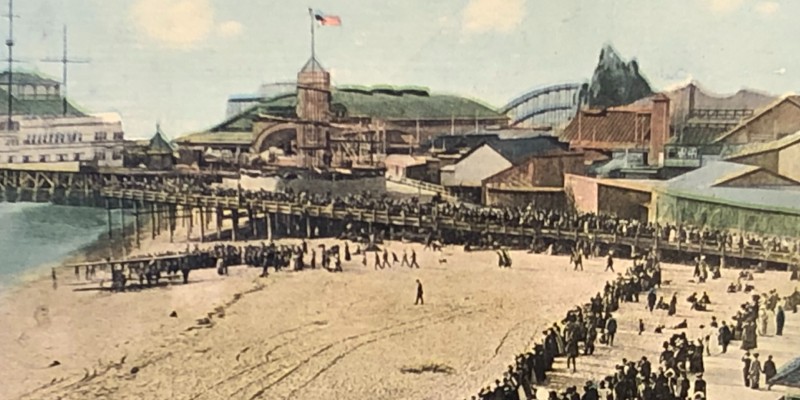

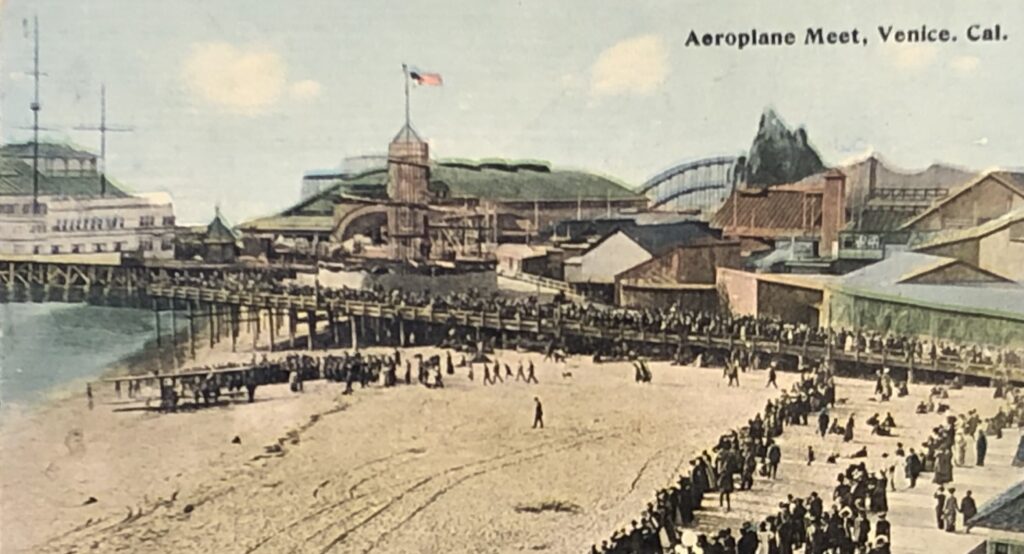

Crowds gathered to see a biplane that landed on the beach at Venice in 1913. (Author Collection)

Crowds gathered to see a biplane that landed on the beach at Venice in 1913. (Author Collection)

“Aviation Field Battle in the Venice Court,” screamed a front-page headline in the city’s Evening Vanguard. Journalists turned up for the hearing expecting legal fireworks. Heney, who had once shot and killed – in self-defence – a man he was suing, was “one of the most famous lawyers living,” one reporter gushed. His “remarkable powers as a court lawyer, his fiery eloquence” and “the novelty of arresting an attorney with his clients” made a big local story even more newsworthy. Perhaps thanks to Heney’s eloquence, criminal charges against all nine men were dismissed. The dispute moved to the civil courts, where DeLay won an injunction banning Frey and his supporters from the airfield and barring them “from interfering with the DeLays in any way in the aviation business.” B.H. DeLay also demanded $10,000 in damages – almost $150,000 in today’s terms – from Frey’s group, but it is not clear whether his claim succeeded.

After the deadly Independence Day crash two years later, the messy legal battle looked like a possible motive for murder. “DeLay has numerous enemies in the bay district,” the Evening Vanguard reminded its readers, “in spite of his pleasing personality.”

One of DeLay’s close friends, a man named Charles Raymond, went public with allegations the Wasp had been tampered with. Bolts attaching the web-like struts to the upper and lower wings were only three-eighths of an inch in diameter, he claimed. More robust, three-quarter-inch bolts should have been used. The smaller bolts had “slipped out of place,” one news report explained, “and forced a loosening of the struts holding the wings.”

Undersized bolts might have accounted for the sudden folding of the plane’s wings. And Raymond said it would have been easy for someone to sabotage DeLay’s plane as it sat in its hangar. The press needed no further convincing. “Aviator Believed Murdered in Air,” Washington, D.C.’s Evening Star reported. A photograph of DeLay appeared in newspapers across the country, under the headline, “Police Are Investigating First Aerial Murder.” One of the few dissenting voices was the Los Angeles Times, which suggested the plane had been built “for straight flying and not for stunts.”

The murder allegation, however, was discounted within days. After “a complete investigation,” the Long Beach Telegram reported five days after the crash, police had “discarded the theory that the plane had been tampered with.” The allegation of sabotage took a further hit when Charles Raymond admitted he had not personally recovered undersized bolts from the burned wreckage. News reports that “he had found a faulty pin in the death machine,” the Telegram revealed, were “not founded on fact.”

Were DeLay and Short the first victims of “airplane murder,” as Time magazine termed it? Ninety-nine years later, what – or who – caused their plane to break apart in mid-air remains a mystery.