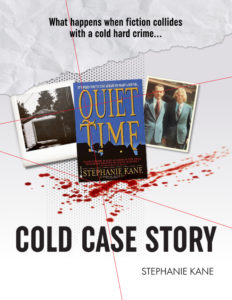

Quiet Time, my first mystery, was a fictionalized version of the brutal murder of a suburban housewife. Not just any housewife, but Betty Frye, on the eve of my marriage to her son. Back in 1973, he and I were college students at CU in Boulder, practicing karate and living together on the Hill. The morning Betty was murdered, I spoke with her; hours later, I saw her killer. Her death made me a crime writer.

Quiet Time was my lab for learning fiction craft. The manuscript underwent twenty-odd drafts, each more heavily fictionalized. I wasn’t imaginative enough to invent brand-new characters, though I did change the killer. And the ending was entirely made up, since in real life he’d walked. Having justice prevail made the story cathartic.

In 2001, when Bantam acquired Quiet Time, I was frank about its origins. I met with Bantam’s legal team and made more changes. The book was published under a pen name to make its connection to Betty’s murder even less recognizable, but the title itself escaped scrutiny: “quiet time” was what her kids called being forbidden to make noise while she lay in the dark.

How much of Quiet Time was true?

Quiet Time’s protagonist was a thinly-veiled version of me, a Jewish girl from Brooklyn who’d gone to CU to put 2000 miles between her and her folks. Only, of course, to fall in love with a boy whose parents were bound to hate everything about her. Also true was the depiction of the day of Betty’s murder: her phone call that morning to our flat, and the unexpected arrival of her husband Duane at the karate studio, in clothes too heavy for the weather and with a nasty bruise on his head. Except Bantam made me change the karate studio to a hockey rink.

But Quiet Time wasn’t based just on memories.

In 1973, Duane Frye had been indicted for his wife’s murder. The charges were inexplicably dropped, and for the nine years I was married to their son, the crime was not discussed. After we divorced, I tunneled into an existence strangely like my protagonist’s: corporate lawyer by day, haunted at night by Betty’s murder and the feeling that our wedding had been the catalyst for the explosion of rage that ended her life. By the early 1990s, it was time to put my ghosts to rest.

I’d remarried, and my new husband knew the DA who’d prosecuted Duane in 1973. He told us the case was blown by an old-timer, a highway-patrol Gunther Toody or Barney Fife. The DA gave me some fragments of microfiche reports which mentioned a cop named Sendle, and a trip to the courthouse for the 1973 file yielded a white-on-grey transcript of Sendle’s grand jury testimony. I couldn’t tell how old Sendle was, but he seemed sharper than I’d expected. Quiet Time’s cop split the difference: paunchy Ray Burt, on the verge of retirement, haunted by his own ghosts, but with a certain savviness. For my catharsis, I needed someone who actually cared.

So, at Bantam’s request, I moved Quiet Time’s timeline up ten years, changed Denver and Boulder to Widmark and Stanley, and purged all references to karate and Colorado (though New Mexico was allowed to remain a neighboring state). When the novel came out, nobody connected it to Betty’s murder. Published the week of 9/11, Quiet Time had a short life and a quick death.

Then in 2005, Duane’s sister saw me interviewed on a late-night rerun of a canceled public TV show. She recognized me, read Quiet Time, and came forward with a confession her brother had made. A cold case was opened, and overnight my novel and I became targets of the defense. The theory was laughable: that I’d conspired with Duane’s 78-year-old sister, whom I hadn’t seen in thirty years, to fabricate his confession in order to sell books. Claiming each Quiet Time draft was a factual statement they could use to impeach me as a witness, Duane’s lawyers subpoenaed all twenty-plus of them, along with my correspondence and notes.

The subpoena placed my writing and thought process under direct attack. An excellent lawyer of my own, and the expert testimony of an English Lit professor, convinced the judge that although all fiction is based on fact, that doesn’t make it fact. My drafts, etc. were eventually protected, but the subpoena made me question what I’d done to real people to exorcise my own ghosts. I’d published three legal thrillers since Quiet Time, but the threat of having my creative processes scrutinized paralyzed me. For the eight years the case was in court, I wrote not a word.

At the same time, in an Orwellian tit-for-tat, the defense’s voluminous pleadings treated me to new versions of myself. Being described as the “former fiancée” of someone to whom you were married for almost a decade is darkly humorous, but not really funny. Nor is a courtroom the ideal place to face real people whom your fiction brought to life and caused to be re-indicted for murder. Witnesses are forbidden to contact each other, but that didn’t stop my former sister-in-law from brushing past me with a look of rage. I notice you’re not coming to the family and saying would you like us to pursue this? she’d told the cold case cops. Nor did it prevent Duane at the defense table screaming “Liar!” at me on the stand.

But Betty’s sisters embraced me. Octogenarians, they drove from as far as Kansas to show up for her month after month in court. The day I testified, two tiny white-haired ladies were in the front row of the gallery, their faces turned trustingly to mine. Afterwards, the eldest whispered to me consolingly, We’re not all like Betty. Because by then everyone knew my wedding to Betty’s son had indeed lit the match.

In 2013. the cold case ended. Suddenly I had access to thousands of pages of interviews and reports, hours of audiotapes and dozens of crime scene photos. Time stopped. I knew each kid on the karate sign-in sheet, heard the pain and hesitation in Betty’s children’s voices when the cold case cops came to their doors, saw the silver-wrapped gift Duane had used as a prop in staging her murder as a burglary-gone-wrong, only to present it to us a month later as their wedding present to us and toast us with the champagne glasses it held. But I still had questions.

So I embarked on interviews of my own. I learned what Betty was like as a girl, and how a marriage that began with such promise ended in such violence. For insight into the written statement Duane made when Betty’s body was found, I consulted an expert in forensic statement analysis. I flew to Arizona to interview Sendle, vigorous and sharp in his seventies, and anything but a bumbler. To my surprise, he’d read Quiet Time. To my relief, he forgave me for portraying him as Ray Burt. The outcome of my investigation is Cold Case Story. It’s what real people actually said and did, not a fiction I wrote to come to terms with my role in a brutal crime.

It’s ironic that Quiet Time, a mystery written to put ghosts to rest, brought them back to life instead. I’d like to say Cold Case Story is an atonement—my chance to do right by the people I fictionalized—or an act of defiance. It is neither. But am I more cautious now about basing my fiction on fact?

Writing Quiet Time and facing its consequences has made me go all-out. To borrow from Frederick Forsythe’s Day of the Jackal, there’s nothing like having your writing thrown back at you on the witness stand in a murder case to focus the mind. For me, there will never be another story like Betty’s, but now I write each book as if it’s my last.

***