On Christmas Eve, 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the Republic of France, boarded his coach bound for the Paris Opera. His coachman, César, was drunk, and sped recklessly past a cart piled with hay partially blocking the street. Seconds later, the cart exploded.

A hundred yards behind, a second coach carrying Bonaparte’s wife, Josephine—delayed by her decision to change scarves—felt the force of the blast, which shattered her window and sent a shard of glass slicing across the hand of her daughter, a fellow passenger. Josephine’s sister-in-law was hurled against the side of the coach, seriously injuring her unborn child.

The cask was packed tight with gunpowder and jagged stones intended to tear flesh and entrails; the press called it an “Infernal Machine.” It destroyed forty-six houses, injured fifty-six bystanders, and killed twenty-two, including a fourteen-year-old girl who’d been duped into holding the cart horse’s reins. But for César’s bottle of wine and Josephine’s scarf, France would have lost its leader and first lady, changing governments for the fifth time in a dozen years and altering the course of world history.

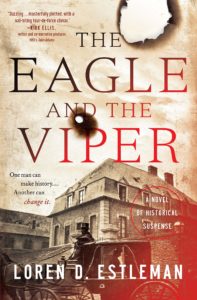

The attempt came within a razor’s-edge of success. Napoleon was still shaken by it sixteen years later, when he was in exile on the island of St. Helena and his sun was set. Recently, archivists have released 33,000 of the former Emperor’s letters, making his personal reflections on such events available to the world. His aggressive counter-measures—and his enemies’ determination to turn a near-miss into a sure thing—propel the action in The Eagle and the Viper.

The “Christmas Eve Plot” was one of thirty attempts to assassinate the French leader; and like most of them it was hatched in England. Despite Great Britain’s persistent claim to have been the courageous nation that withstood a foreign tyrant, its motives from first to last were to destroy the Republic and prevent liberty from reaching its own shores.

As a writer, I was inspired by the sheer size and determination of this exercise in international terrorism. It’s history, not fantasy. I followed a natural train of thought and created The Viper, a lone assassin hired by the British and Royalist conspirators to kill Napoleon and pave the way for the restoration of the French monarchy.

Two hundred years of British propaganda have created most of the false impressions about Napoleon. For one thing, he wasn’t short; and in all his time in power he declared war only once. Apart from the disastrous Russian campaign, all his battles were fought in defense of France. He followed each victory with sweeping reforms in the defeated countries, abolishing slavery, correcting inequities in the justice system, and raising the wages of the working class.

\My decision to wed historical fact with fiction was nothing new. Sir Walter Scott is credited with inventing the historical novel with works like Ivanhoe, Kenilworth, and the Waverley saga. Although he’s the most famous storyteller to stand fictional characters against a real-life backdrop, the tradition had been around for 800 years. We wouldn’t have King Arthur or Robin Hood without it.

Scott shared a passion for the drama of the Napoleonic era with dozens of his successors; he ventured into biography with his nine-volume Life of Napoleon, written from his own point-of-view as a Bonaparte contemporary. A disciple, Alexander Dumas (whose father had commanded the French cavalry during the Egyptian campaign) made Napoleon’s first exile a pivotal point in The Count of Monte Cristo. Leo Tolstoy constructed War and Peace on the foundation of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. Count Tolstoy’s fascination with a man he must have considered his country’s mortal enemy was so great that he fleshed out the epic struggle with extensive research into his personal habits, down to describing the beauty of Napoleon’s hands. Thomas Costain (The Last Love, Ride With Me) and Anthony Burgess (The Napoleon Symphony) brought the subject generations into the 20th century, with fresh infusions of psychoanalysis and modern-day cynicism.

Napoleon himself once said, “My life would make a great novel.” Literature has proven him right.

He was a strong, brilliant, ruthless man who was nonetheless constantly a target for those who would destroy him and everything he represented. Had it not been for that relentless pressure, he wouldn’t have made the fatal decision to declare himself emperor and create a line of succession, in an attempt to secure his own survival by guaranteeing that the revolutionary principles would remain in force no matter what.

In The Eagle and the Viper, I ratcheted up the tension by putting a lone and seemingly invincible professional killer on Napoleon’s scent; a man even more ruthless than his quarry, without the hindrance of anything resembling human conscience; a viper in every sense of the term. And so a world already knocked out of balance by revolution, war, and treachery staggers that much closer to the apocalypse.

Very little more invention was necessary. With a real-life cast that included Joseph Fouché, Bonaparte’s cunning, unscrupulous Minister of Police, Paris Prefect Nicolas Dubois, a detective genius worthy of our own century, the wily spy sisters Saint-Michel, and Georges Cadoudal, a radical Royalist and terrorist leader of the sort all too familiar to us today, the thriller practically wrote itself.

It was a time of improvised explosive devices, terrorist training camps, international assassins, and war on civilians; and it all happened two centuries ago. The world progresses, yet remains the same.

*