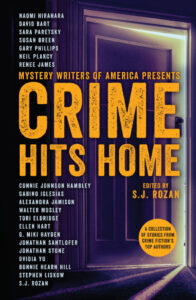

Each year, the Mystery Writers of America (MWA) publishes an anthology of crime stories united by a central theme. This year, the theme was “Crime Hits Home.” Ahead of next week’s Edgar Awards, the contributors to the MWA anthology were asked to reflect on the anthology’s theme. Their answers, below, are as surprising and intriguing as one would expect.

Keep an eye on CrimeReads in the coming days for more MWA content.

Ovidia Yu, “Live Pawns”

The theme of “Home” right now makes me think about refugees and how much is left of your identity when the sanctuary you think of as “home” is taken away from you. I also wanted to write about Chinese people—like me—who’ve only ever been to China as visitors. And how, bizarrely, I feel more instantly ‘at home’ touching down in NYC than in Shanghai simply because the signs are in English.

But I also wanted to write about the home cocoons we create around ourselves for protection and comfort. The protagonist in my story grew up as an outsider in America after her family fled Vietnam—whereas ethnic Chinese they’d lived for generations but never been accepted. My story is about fighting for a space to call home—and also about adapting to the new relationships that come with it.

Steve Liskow, “Jack in a Box”

Over the last two years, “Home” became synonymous with “fortress,” much more than it would have been for me a few years ago. Because of that, I assumed that many submissions would involve a home invasion or a similar idea, so I tried to go in a different direction. Playing around with “home,” I thought of the opposite, “homeless.” My wife, who is better with titles than I am, suggested “Jack in the Box,” and that gave me a lot of the story right away. Jack lived in a box. I decided he was a veteran with PTSD.

I didn’t want to turn the story into a sermon about damaged veterans even though I feel strongly about the issue, and I wanted Jack to be sympathetic without being pathetic, so I tried to make the story funny. Since we see things from Jack’s point of view, I had to SHOW his damage without telling about it, and the stray animals seemed to be a good way to do that.

Jack has some of my traits. He’s kind of a loner and he likes animals. His relationship with Lucy and the others showed me where the story had to go and how it should end long before I got there. That doesn’t always happen, but it felt like a good sign. I’m thrilled to be in a book with such good company.

Neil Plakcy, “Oyster Creek”

When I began writing about George Clay, I knew that he had traveled the world as a Master-At-Arms in the Navy, and that he’d never be able to go back to small-town life after that. But I wanted him to have a sense of home as a place he could return for visits, where everything would always be the same. Disrupting that belief, as well as giving him an opportunity to learn something about his mother and himself, became the framework for “Oyster Creek.”

My vision of home is rooted in the small-town life I grew up in, where the VFW and the Boy Scouts marched down Main Street in the Memorial Day parade, where kids put baseball cards between the spokes of their bicycles and you’d see your elementary school teacher at the grocery and realize she had a life outside the classroom. Because “Oyster Creek” takes place in the 1960s, I could create that kind of hometown for George.

When crime hits a place like that—well, it will never be the same again.

David Bart, “The World’s Oldest Living Detective”

Home can be defined as any dwelling, grand or humble, in which you find yourself. Ethan Brock lives in a communal residence for seniors and is unexpectedly enlisted to solve a contemporary mystery, and in the doing he remembers an unusual case from his past as a private investigator; a case in which he found himself confronted with a moral dilemma. This premise allowed me to explore the idea that, despite diminished abilities, a person can still be productive, motivated by past successes as well as regrets. Life in a retirement home might be considered by some as merely existing in a kind of holding pattern; but for Ethan it offered an opportunity to continue, for as long as it lasts, a life well lived.

Tori Eldridge, “Missing on Kaua‘i”

Like most native Hawaiians, I have felt the pull to revitalize my connection with the Hawaiian language, our sovereign history, and our land. Crime Hits Home gave me an opportunity to dive into issues that many of the kanaka maoli (native Hawaiian) homesteaders are struggling with today while setting an adventurous mystery on the gorgeous island of Kaua‘i. As with my Lily Wong series, which draws from the Chinese Norwegian side of my heritage, “Missing on Kaua‘i” features the complex and multicultural family of Makalani Pahukula, an Oregon ranger home for her grandmother’s birthday lū‘au and finds two of her cousins missing and her loving ‘ohana at each other’s throats. Writing and researching this story enriched my life and inspired the novel that I’m working on today—all because of the inviting theme of Crime Hits Home.

From the moment I heard the title, I knew my protagonist would come home to Hawai‘i and that the story would revolve around family. And since our eldest son was recently married on Kaua‘i, that island—always my favorite—was freshest in my mind.

Jonathan Stone, “The Relentless Flow of the Amazon”

I think for fiction writers confronted with the pandemic, there were basically two experiences: a) write about ANYTHING BUT the pandemic (escape it, let your imagination take you anywhere else)—or, b) you HAVE to write about it, it’s so completely impacting global life, how can you not? I was in the second camp—although I immediately ran into an odd and embarrassing problem—how little it was altering things for me personally. I’m retired, my kids are grown, my wife and I continue to rattle around in the house we’ve lived in for over thirty years—me typing away happily/madly over the garage, her making art in our basement studio—and cripes, NOTHING HAD CHANGED! Well, ok, one thing. We were being super cautious, not going out, letting no one else in, having everything delivered—groceries, other necessities––and therein was the germ (ha-ha) of a story for me.

Naomi Hirahara, “Grand Garden”

Certainly, during the pandemic my thoughts have been more on the past than on the future. But I’m a context person, at least that’s what my CliftonStrengths assessment says. I do think that I grapple with history to make sense of our present trials and tribulations. I wrote about an old-school Japanese-style garden in my hometown of Pasadena, California, because I plan to explore this time period (early 1900s) in a future mystery novel. It’s based on a real garden in which an immigrant couple from Japan raised two American-born children. It’s fascinating to think how a place of beauty—one that we Americans treasure—can also serve as a type of prison for the children. They are forever branded as “the exotic other.” Subconsciously—and that’s where the work usually happens—I probably was drawn to write about a garden because such places have been such a refuge for me during the lockdown. But there’s a darker side to this highly manicured controlled environment. That’s how “Grand Garden” was born.

Miki Hayden, “Forever Unconquered”

Addressing a theme such as Crime Hits Home, I wanted to find an intriguing home to bring to life. I’ve written a few stories and a couple of novels with Native American (and Native Hawaiian) characters and settings, and in this case, I chose a character from the Muskoki, the Seminole, tribe. Billie Sua came with a Florida Everglades setting. A bit of research later—details and research are always needed—I had my story. This is my third story in an MWA anthology. I won an Edgar for a much earlier story set in Haiti.

Jonathan Santlofer, “Private Dancer”

From the outset, I wanted to pervert the concept of home, to tell a story with a somewhat unreliable narrator whose idea of home was based on a lie. (The thought of anything to do with home-sweet-home never passed my mind.) I also liked the idea of writing about someone rich, who had everything, and was going to lose it. Most of my short stories turn the tables on the narrator, and they get what they deserve; I have always liked the idea of revenge (for those who deserve it). I had at least three or four ideas for this theme, one I started, a modern Cain and Abel story, seemed too coy, and was soon abandoned. After that, I wrote one about a psychopath, a young (very attractive) serial killer, who yearns for home so badly he kills for it. I can’t say exactly why I tossed that completed story out (I’d guess because my most recent novel, “The Last Mona Lisa,” had just come out and my head was muddled), but I wanted something else. I went back to a story idea I had started a while ago, mostly jotted down in notes, and it eventually became “Private Dancer.”

I can’t say that the pandemic affected my story, though who knows; everything affects one’s work, doesn’t it? The truth is, as a writer and artist I’ve spent so much of life in solitary it was as if I’d been preparing for this moment.

Connie Johnson Hambley, “Currents”

For most law-abiding citizens, a home is a place of refuge, a place to recharge when the demands of the outside world become too much and we just need to take a beat. But what if home was a hideout, like an isolated, uncharted island? Who lives there? What or who are they hiding from? What if a woman washes up on its shore along with the floating debris of the Pacific Ocean Garbage Patch?

I wanted to breed tension into the sanctity of home and unwanted intrusions are terrific playthings. With the pandemic, we have become more sensitive to threats not just from humans but the natural world as well. We’ve begun to see scientists as the ultimate protectors. In Currents, I found delightful answers to my questions. The trick of a short story is to identify the tension up front and have it resolved in one way or another while playing fair with the reader and breeding in the beloved twist. So, in my ever-scheming, crime-riddled mind, I put the home of a scientist-turned-assassin in jeopardy from an unwanted intruder. Let the games begin.

Renee James, “Stalking Adolf:” For me, and for my story “Stalking Adolf”, home was both a literal place and symbolically, a place of safety and privacy. The story is about a transgender woman whose stalker has brazenly invaded her home as part of a pattern of intimidation. It is the story’s inciting event, because it signals to her she must take action. There is no longer any room for procrastination—her daughter’s life and her own are in mortal danger.

I don’t think the pandemic changed my perception of “home”, though it may have made me somewhat more paranoid than usual. This was only the second short story I had ever written, so I wanted to keep it simple in terms of plot and conflict. I also wanted to write something set in the period of the Trump presidency which was so wildly different from the America I lived in for many decades. The bullying mentality of the MAGA people, especially with regard to visible minorities, was something I’ve always wanted to make sure we writers documented for posterity, though in the end, my story is a morality play about how “moral” people deal with threats posed by enemies, not about the morality of Trump’s political movement.

Gary Phillips, “Flip Top”

Naturally the old adage about how you can’t go home again came to mind. While that’s not an original thought, the saying nonetheless stayed with me, goading me to interpret it in another way for the story I wanted to tell. My main character does indeed come home, for a funeral, and is welcomed, he’s the guy who made good. But a seemingly innocent occurrence, an everyday bit of play between two children reels him back to the past and sets him in motion in the present. For sure the pandemic was on my mind, and I’ve included references to it in a couple of other short stories, but I wanted “Flip Top” my story in the anthology to have a timeless quality so there’s no mention of that—though the Rodney King riots of ’92 are mentioned as my protagonist was a child then—like the two kids he sees goofing around as the story begins.

Susan Breen, “Banana Island”

Some years back, I was on a walking tour of Long Island City and the guide kept talking about how dramatically home prices had risen. He pointed to one little house and said it had just sold for $2 million. Immediately I began wondering how that sort of windfall could affect a family. What if one cousin owned a house and another just rented? What sort of jealousy and bitterness could arise? What if the very place that you considered home became weaponized?

At the same time, I had been sketching out a character, Marly Bingham, who worked for the IRS as a scam baiter. These are the people who are supposed to distract scammers from cheating you out of your money. The idea is that if a scammer is busy talking to an IRS agent, he won’t be going after someone more innocent. The problem is, in my mind, that if you spend a year talking to someone, no matter your motives, some sort of authentic relationship is going to bubble up. So I had Marly, plus a scammer who dreamed of moving to wealthy Banana Island in Africa, and a bunch of Marly’s quarrelling cousins, and I put them all in Long Island City.

A.P. Jamison, “Haunted Home on the Range”

How did you envision home? Home to me is a safe space filled with the people and animals I love. This story was inspired by two family members I lost just before Covid in 2019. My main character, Gus, is an eleven-year old cowgirl private detective who lives on her family’s ranch with her best friend Marshmallow, a Golden Retriever. And this ranch—which has been in the family for generations—is Gus’s favorite place in the whole world and in writing this story the ranch became mine.

Is it different in this stage of the pandemic than how you might have written it four years earlier? Yes.With travel halted and the world upended, I felt that readers might enjoy being able to escape the real world for a moment and hang out on a big ranch solving a murder mystery with a savvy, cowboy-boot wearing, pecan-pie loving girl and her dog.

How did you decide to approach the theme? The theme of home really called out to me especially during a time of both hunkering down without extended family members and missing that connection to “home.” Then, I thought about what would be the worst thing that could happen to Gus on her beloved ranch aside from the accidental death of her parents a few years earlier. What if someone was murdered on the ranch and Gus finds the victim while visiting her parents’ grave. That was a crime that sure hit home.

Were there other avenues you considered pursuing? Yes, there were two earlier other versions set around San Antonio’s Fiesta. But since the theme was Crime Hits Home, the majority of this story, including the murder, is now set on the ranch.

Or certain avenues you wanted to be sure to include? I hope the reader feels the happiness and heart at the ranch as well as the sense of family, friends and fun until the shock and terror you’d feel after a murder at your home. I also wanted the reader to see that despite Gus’s age, she is a smart little detective who together with Marshmallow solves this murder on her ranch. Finally, I found that getting to know Detectives Gus and Marshmallow was such fun that this story inspired my new novel.

S.J. Rozan, “Playing for Keeps”

I saw “home” as place someone who’d been uprooted could start again, and would fight hard to keep.

Is it different in this stage of the pandemic than how you might have written about it a few years earlier?

I don’t think so, not this story. Of course, you never know, because if there hadn’t been a pandemic, my whole thinking about pretty much everything would have been different.

How did you decide to approach the theme?

I wanted to write about a child survivor of war and atrocity, and I wanted to write from her point of view.

Were there other avenues you considered pursuing? Or certain aspects that you wanted to be sure to include?

As usually happens to me with a short story (as opposed to my process with a novel) the idea, once it came, just continued to grow. I didn’t consider anything else.

***