In 1830, the murder of wealthy slaver Joseph White shook all of Salem, Massachusetts.

___________________________________

“What other dungeon is so dark as one’s own heart? What jailor so inexorable as one’s self?” —Nathaniel Hawthorne, The House of the Seven Gables (1851)

One young man who most certainly possessed knowledge of the town’s darker maritime heritage was twenty-six-year-old Salem native Nathaniel Hawthorne. The would-be writer had graduated from Bowdoin College three years before the White murder, in 1827, as part of a class that included Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and future president Franklin Pierce. At the time of the murder, Hawthorne—who’d recently added a w to his ancestral name Hathorne—lived with his mother and sisters in a home that his mother’s brother Robert Manning had built for them at 31 (now 26) Dearborn Street. By 1830 he had already written one novel, Fanshawe, which he self-published anonymously through Boston’s Marsh & Capen publishing house in October 1828. Although it received generally good reviews, the book did not sell well. Eventually Hawthorne gathered together the many unsold copies and burned them. He would later deny being the book’s author, as he eventually came to think of it as amateurish.

At this time, Hawthorne was no stranger to Salem’s lowlife. On a particular 4th of July, which also happened to be his birthday, he happily wandered the waterfront among “customers rather riotous, yet funny, calling loudly and whimsically for what they want,—young sailors & c; a young fellow and a girl coming arm in arm; perhaps two girls approaching the booth, and getting into conversation with the he-folks thereabout, while old knowing codgers wink to one another thereby indicating their opinion that these ladies are of easy virtue.” He also noted “a knock-down between two half-stewed fellows in the crowd—a knock-down without a heavy blow, the receiver being scarcely able to keep his footing at any rate. Shoutings and hallooings, laughter,—oaths— generally a good-natured result.”

Hawthorne likely knew of Salem’s slaving sins not just because of tales told in the waterfront bars that he now frequented but also because the young man already, at this early stage of life, made a morbid habit of dwelling upon Salem’s many hidden shames, doing so with a dark fascination that had already influenced (in fact, come to define) his novice efforts at fiction. As one historian has noted, Hawthorne perceived in the Salem of his time “little more than a melancholy process of decay, and a dusky background for romances of a century more remote.” Still, Hawthorne would write in his preface to The Scarlet Letter that he admired the ancient Salem families who “from father to son, for above a hundred years, . . . followed the sea; a gray-headed shipmaster in each generation retiring from the quarter-deck to the homestead, while a boy of fourteen took the hereditary place before the mast, confronting the salt spray and the gale which had blustered against his sire and grandsire.”

Hawthorne did indeed find in Salem “a dusky background for romances of a century more remote.” In one of his earliest stories, “Alice Doane’s Appeal,” Hawthorne described Salem’s Gallows Hill as the “field where superstition won her darkest triumph; the high place where our fathers set up their shame, to the mournful gaze of generations now remote. The dust of martyrs was beneath our feet.” Although Hawthorne spoke generally here of “our fathers,” he might just as well have said “my fathers.” Hawthorne’s own great-great-grandfather John Hathorne, who died in 1717, had served as a judge—and not just a judge, but a most strident and enthusiastic one—at the Salem witch trials. In the end, Hathorne caused more than twenty people to go to their deaths (nineteen hung, one crushed under heavy stones for failure to testify, and four who died of neglect in their cells while waiting to be hung).

Although ostensibly a judge, Hathorne had acted more like a prosecutor, attacking each defendant in turn and joining accusers in presuming guilt. What is more, it had been Hathorne who adopted the policy of insisting that defendants name their satanic “accomplices” in exchange for the possibility of leniency. In this way, Judge Hathorne drastically increased the number of those accused and the number sent to die. Although at least one of Hathorne’s fellow judges would eventually express regret for his role in the mania of Salem’s witch scare, Hathorne never did. In fact, on the very day of the very last executions, Hathorne was meeting with the bombastic Puritan preacher and pamphleteer Cotton Mather, along with others, to discuss publishing a record of the Salem proceedings that would, he hoped, encourage similar prosecutions elsewhere throughout New England.

Judge Hathorne conducted himself in a manner—and with a ferocity—practiced previously by his own father, William Hathorne, who in 1630 traveled to Massachusetts with John Winthrop aboard the Arabella, settling in Salem some six years later. This Hathorne—although a maker and seller of “strong waters”—was nevertheless a devout Puritan who gladly served as magistrate in his adopted community and became notorious for both the severity and ingenuity of the punishments he meted out for violations of civil and religious order.

Gossips variously had their ears cut off or holes bored into their tongues with red hot pokers. A burglar, after losing a hand, might also have his forehead branded with the letter B. In one particular case, a woman found “guilty” of being a Quaker was stripped naked from the waist up, bound to the tail of a cart, and dragged down Salem’s main thoroughfare while being beaten from behind by a constable with a whip of knotted cords. Most murderers were—appropriately—hung. But unlucky murderers found themselves locked away to starve, all at William Hathorne’s whim.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s more immediate ancestry on his father’s side was maritime. Judge John Hathorne’s own brother, Captain William Hathorne the younger, spent many years at sea before becoming a farmer. The judge’s son Captain Joseph Hathorne (Nathaniel’s great-grandfather) likewise had a long career on the oceans of the world before reverting to farming, as did Joseph’s brother, another Captain William Hathorne. Joseph’s son Daniel (Nathaniel’s grandfather) commanded a battleship named the True American during the Revolutionary War. Upon the occasion of his death in 1796, his body was carried to Charter Street Burying Point in a grand procession. According to the Salem Gazette, “The corpse was preceded by the Marine Society. . . . The flags of the ships in port were half-mast high—and the numerous [parties who] attended on this melancholy occasion fully evinced the regret they felt at the departure of their worthy townsman.”

In turn, Nathaniel’s father, Captain Nathaniel Hathorne Sr.—like others of the family a member of the East India Marine Society—became a ship’s captain but died of yellow fever in Paramaribo, Dutch Suriname, during the year 1808, when the younger Nathaniel was just four years old. (Four years earlier, Captain Nathaniel Hathorne’s brother, Daniel Hathorne Jr., had died at sea.) At the time of his death, Captain Nathaniel was in command of a vessel owned by Salem’s Captain Nathaniel Silsbee: a brig of 154 tons, the Nabby. Perhaps because of his father’s and uncle’s tragedies, young Nathaniel never aspired to a nautical career. In 1825, Hawthorne wrote a poem, “The Ocean,” in which he seemed to commemorate his father’s burial at sea some seventeen years earlier.

The Ocean has its silent caves,

Deep, quiet, and alone;

Though there be fury on the waves,

Beneath them there is none.

The awful spirits of the deep

Hold their communion there;

And there are those for whom we weep,

The young, the bright, the fair.

Calmly the wearied seamen rest

Beneath their own blue sea.

The ocean solitudes are blest,

For there is purity.

The earth has guilt, the earth has care,

Unquiet are its graves;

But peaceful sleep is ever there,

Beneath the dark blue waves.

On Nathaniel’s mother’s side of the family, Nathaniel’s grandfather Richard Manning Jr. founded the Boston and Salem Stagecoach Line, which all of his sons save for one continued to operate after Richard’s death in 1812. Manning left an estate valued in excess of $50,000, some $33,000 of this in real estate holdings. As her share of the inheritance, Elizabeth Hathorne (née Manning) received a relatively paltry sum of $200 (about $5,400 today) annually, this administered by her brother, Robert Manning, who tended to the interests and needs of Elizabeth and her family.

The odious heritage of the witch trials wore heavy with Hawthorne, as did most other aspects of traditional New England Puritanism. He was to spend a lifetime pondering what it all meant both culturally and spiritually. The ghosts of Salem’s past imbued the landscape of Hawthorne’s imagination, carrying with them a stain of self-righteous sin that could never be washed away, no matter how many rains fell. One critic has called this Hawthorne’s “mystical blackness.” In his essay “New England Two Centuries Ago,” James Russell Lowell commented, “I never thought it an abatement of Hawthorne’s genius that he came lineally from one who sat in judgment on the witches in 1692; it was interesting rather to trace something hereditary in the somber character of his imagination, continually vexing itself to account for the origin of evil, and baffled for want of that simple solution in a personal devil.”

Hawthorne’s Salem was a place of masks, ironies, and a multitude of neverending blasphemies—as was the wider world that Salem, to Hawthorne’s mind, represented in microcosm. Mankind by its nature was tainted, albeit beneath the skin: in hidden corners, hidden thoughts, and hidden crimes. Therefore, what happened on Essex Street on the particular moonlit night of April 6, 1830, and the complex web of deceit that was to spin off from it, probably came as no surprise to him, not in the least.

___________________________________

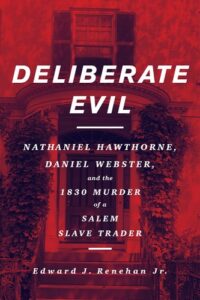

Excerpted from Deliberate Evil: Nathaniel Hawthorne, Daniel Webster, and the 1830 Murder of a Salem Slave Trader, by Edward J. Renehan Jr. Published by Chicago Review Press. Copyright 2021, Edward J. Renehan Jr. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.