I fell in love with reading and mysteries at the same time through Trixie Belden mysteries. While our lives had nothing in common, I identified with Trixie over our curly hair. It would be decades before I felt that moment of identity with a character again.

I learned to avoid mysteries with Native American characters after sampling several written by non-Natives. They depicted Native characters with the same stereotypes as TV Indians, which represented no one I knew.

Tony Hillerman changed that.

I discovered Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee while reading Hillerman’s Thief of Time in 1988. Though written by a non-Native, Hillerman’s Leaphorn and Chee series opened my eyes to what a mystery novel’s story and main character could be. I had not thought of blending my Kiowa culture with a mystery in a novel before.

Hillerman approached the Navajo culture and each character with a depth of knowledge I had not seen in previous stories involving Native characters. His characters were treated with respect, created as three-dimensional people, and were main characters, not just a mystic or amusing sidekick. In each novel, Hillerman revealed unique crimes and injustices faced in daily Native life that other novels had neglected.

I devoured everything Tony Hillerman wrote. Not only for the intricate mysteries he put together in each novel, but also the insights provided about Navajos, and other Native American cultures. Each novel in the Leaphorn and Chee series had real characters in the midst of relatable stories. Hillerman achieved his authentic voice not only through studies and research, but through learning Native oral traditions directly from the source. He forged strong connections within Navajo Nation and often had his manuscripts reviewed by elders in the tribe.

Anne Hillerman breathed new life into the Leaphorn and Chee mysteries by continuing the popular series with an expanded role for Navajo Tribal Police Officer Bernadette “Bernie” Manuelito. Anne’s Bernie evolved into a take-charge police officer comparable to Leaphorn and Chee.

After reading Hillerman’s Leaphorn and Chee mystery series, the story I always wanted to write began taking form. It was as if I needed to read what was possible to find my voice and characters.

I discovered another non-native author writing Native American-centric mysteries, this time with an Arapaho main character. Margaret Coel’s Wind River mysteries partnered Arapaho attorney Vicky Holden with Jesuit priest Father John O’Malley to solve mysteries in and around the Wind River reservation.

While I consumed all twenty of her books in the series, I was always disappointed that Vicky Holden was viewed as an outsider in her tribe. Vicky was criticized for leaving her children with her parents while she sought an education to be able to improve their lives. This aspect was foreign to me. In the Kiowa culture you honor the Creator by being all you can be—fulfilling your potential. Vicky fought to fulfill her potential by becoming an attorney who returned to the reservation to help her people. I yearned for Vicky Holden to be celebrated within the Arapaho tribe for the warrior she was.

While I wasn’t yet writing my novel, I was living with it. Coel’s novels added to my imagination. When I drifted in thought, scenes unfolded, characters stepped forward, and possibilities developed. Yet, I still had not found my voice, my story to tell.

To my delight, I discovered my first Native American author writing a mystery series. Mardi Oakley Medawar of Cherokee descent penned a historical mystery series featuring odd-man out, Tay-bodal, a late 19th century Kiowa healer. Tay-bodal solved murders with logic, science, and thoughtful deduction. Medawar’s four-book series showed Native Americans as fully fleshed-out, real people struggling to survive during a turbulent period. Each novel is historically accurate and true to the culture I know.

From the first page of Medawar’s Death at Rainy Mountain I knew I had found something unique in the genre. Her portrayal of 1860s Kiowa life rang true. Medawar knew Kiowa cultural nuances, our oral traditions, and our side of historical events. While not Kiowa, Medawar gained insights to the culture and history through collaboration with Kiowa elder and Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Oklahoma, Gus Palmer Jr.

Medawar’s Tay-bodal mystery series had a depth of insights and inside information missing from the other novels featuring Native Americans. For the first time, a book mirrored my reflection.

After reading Medawar’s four novels, my Kiowa mixed-race protagonist Mud, took form, I envisioned her Kiowa Naming Ceremony. I found my voice, story, and setting. It would start in Kiowa country and I would blend historical facts, and oral traditions in every mystery. I knew it could be done—the Hillermans, Coel, and Medawar proved it.

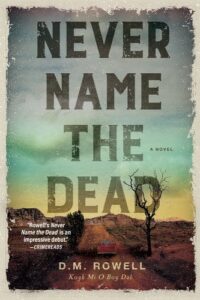

My path to writing my first Native American novel, Never Name the Dead, started with an awakening of possibilities. The Hillermans, Coel, and Medawar made my Mud Sawpole mysteries possible—they made me believe that I had a story to tell that others would want to read.

While I have nothing but appreciation and admiration for the Hillermans and Coel, I am delighted to see the number of Native American mysteries written by Natives coming out in 2022. CrimeRead’s An Unprecedented Era of Native American Noir article, highlights fourteen new and upcoming releases for 2022 and 2023. I’ve added each to my reading list.

I owe a lot to Hillerman and Coel. They both woke me to the possibilities, helped lead me to my story. But it is refreshing to hear the voices of Native Americans telling their own stories, sharing insights and perspectives into our cultures and daily lives that no outsider can truly bring. The mystery genre is advanced when Native writers bring their lived experience with fresh perspectives on solving crimes and murders.

I am proud to be part of the emerging Natives telling our stories, our way.

***