Many of the clichés from the detective stories of the Golden Age of Mystery Writing and the old black and white films of the 1940s pop up in Murder at Black Oaks, the latest entry in my Robin Lockwood series. But you have to go back in time to my days in elementary school to learn why I put them and many others in a contemporary legal thriller.

I have been a voracious reader, devouring two to three books a week, since elementary school. The books I liked the most were the fair play mysteries of Ellery Queen, with their bizarre murders and clues you could use to figure out whodunnit, and Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason courtroom thrillers.

Perry inspired my twenty-five-year career as a criminal defense attorney, during which I represented thirty clients charged with homicide, including several who faced the death penalty. Ellery inspired me to write novels with surprise endings and the clues I sprinkle in them.

When I got to junior high school, I discovered John Dickson Carr’s locked room mysteries, where people were always getting murdered under impossible conditions, and Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot with his little gray cells.

By the time I was twelve I had decided that I would be a criminal defense attorney like Perry Mason and try murder cases when I grew up. That goal seemed attainable. After all, a lot of people went to law school and became attorneys. But reading the novels from the thirties, forties and fifties – the Golden Age of Mystery Writing –had a negative impact on me. I didn’t know any writers and I didn’t know anyone who knew any writers, and I was in awe of anyone who could imagine a murder in a locked room where the victim is suspended on African spears and his clothes are on backward like Ellery Queen did in The Chinese Orange Mystery. So, the idea of writing my own novel never entered my head.

After college, I spent two years in the Peace Corps in Liberia, West Africa. Then I went to NYU law school. I had been teaching school to pay my tuition and rent, but my wife graduated from college and got a job just before my last semester in law school, a summer session. That meant that I didn’t have to teach school, so I had a lot of free time. I decided to use it to solve one of life’s great mysteries, which was “how do these writers fill up 400 pages with words?”

I spent the next two years writing a novel based on my experiences in Africa between college and law school. The book was terrible, but I loved writing it and writing became a hobby.

In 1978, a series of bizarre events led to the publication of Heartstone, which was nominated for an Edgar. After publishing one more novel in 1981, I stopped writing to concentrate on my law practice. Then, in 1993, through a second series of bizarre events, I published Gone But Not Forgotten, which, to my shock and surprise, became a huge bestseller. In 1996, after twenty-five very exciting years as an attorney, I retired to write full-time.

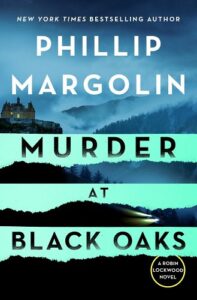

There’s a rule for writing that says that you should write what you know, and all of my twenty plus novels have a lawyer and a murder, but I work hard to make sure that I don’t repeat my plots. When I finished writing The Darkest Place, the fifth entry in my Robin Lockwood series, I started thinking about the plot of my next novel. I had been rereading the Ellery Queen and John Dickson Carr locked room mysteries and I got an idea. I decided to write a novel that contained every cliché from the mysteries of the Golden Age, and that led to the creation of Murder at Black Oaks, which is an homage to Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen, John Dickson Carr, Erle Stanley Gardner and all of the writers who have made reading so enjoyable for me.

In Murder at Black Oaks, Robin Lockwood is hired by Frank Melville to free an innocent man, who has spent thirty years in prison for a murder he did not commit. Like Perry Mason, Robin succeeds and brings Jose Alvarez to Black Oaks to celebrate.

Black Oaks, which sits at the top of Solitude Mountain, is a brick-by-brick recreation of a haunted manor house on the English moors. A curse involving werewolves was laid on the original manor house, which had secret passage ways and a dungeon where horrible acts of torture were performed.

Also staying at the mansion are a horribly scarred butler, a washed-up movie actor who is suspected of murdering his wife ten years before, and a gold-digging assistant. Soon after Robin arrives, a torrential rain causes landslides that isolate the mansion. To make matters worse, a detective arrives and informs everyone that an inmate from the hospital for the criminally insane has escaped. Then someone is murdered in a cage elevator that is trapped between the second and third floors of Black Oaks. The killer had to be in the elevator to commit the murder, but only the victim is in the cage.

The hardest part of writing Murder at Black Oaks was the creation of my impossible crime. I am pretty good at figuring out whodunit when I read a mystery novel, but I don’t have a lot of success figuring out how a victim was killed in a locked room. So, I went on the Internet looking for help.

I found several excellent articles listing writers favorite locked room mysteries. The Great Locked Room Mystery: My Top 10 Impossible Crimes by Tom Mead, which was published in CrimeReads, and The Top 10 Locked Room Mysteries by Adrian McKinty provided excellent lists of challenging mysteries. But the tutorial provided by John Dickson Carr, the undisputed champion of the locked room/impossible crime genre, saved the day.

In 1935, Mr. Carr published The Hollow Man in England. (It was called The Three Coffins when it was published in the United States). In one of the chapters, Dr. Gideon Fell discusses every possible solution to a locked room situation. With the lecture as a guide, I was able to create my impossible crime situation.

I have had a ball writing my homage to the writers who inspired me. I hope Readers have as much fun reading it as I had writing it.

***