Does the chaos and corruption of America’s best city create an atmosphere where the twisted and cold souls of literary anti-heroes thrive? Or is it the anonymity the city provides that allows for even those with the highest levels of privilege and wealth to live disconnected and lonely lives?

Is everything we think we want really going to get us anywhere? Some of my favorite literary anti-heroes answer those questions as they expose the reality of how New York City privilege and excess can lead to anything but happiness.

American Psycho, by Brett Easton Ellis (1991)

Patrick Bateman, Vice President at Pierce & Pierce, living in a gorgeous apartment with a coveted address, invited to all the important parties, and able to secure almost every exclusive restaurant reservation. His days are spent daydreaming about the brutal murders he’s just committed or those he is about to commit. He manipulates and uses people, only for his own benefit, never willing or able to connect on any deeper level. Set in the restaurants, offices and homes of New York’s wealthy elite, Bateman slowly loses his mind. Seemingly in possession of exactly what the world tells us we want out of life—good looks, charm, elite education and employment—in the end, it’s loneliness and fear that define Patrick Bateman’s life.

The Catcher in the Rye, by J.D. Salinger (1951)

Holden Caulfield, one of the most controversial characters in literature, at once hated and revered, seems unable to find connection and satisfaction in any of his social encounters. He arrives back in New York after his expulsion from the prestigious and exclusive Pencey Prep in Pennsylvania. Depressed and chronically disappointed, feeling as though everyone except for him is a phony, Caulfield wishes to eventually become what he describes as “the catcher in the rye.” A person whose job it is to ensure that children playing in rye fields do not accidentally fall from the cliff at the edge of the rye fields. He sees it as saving children from losing their innocence, while Holden Caulfield himself is adrift in losing his own.

The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton (1920)

Raised at the peak of New York City high society, Newland Archer finds himself impaled upon the horns of a love dilemma. While he has been joyfully awaiting his marriage to a more than suitable social counterpart, May Welland, he is suddenly thrown into a sea of turmoil when he falls for her striking and glamorous cousin. Tied tightly by the binds of decent society, Archer suffers terribly with his predicament: should we do what society expects from us and remain proper and respectable but miserable? Or do we pursue our true passion, at the expense of our social status? A terrible quandary, indeed.

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

Nick Carraway, beguiled by the mystery and opulence of Jay Gatsby’s famous Long Island parties, finds himself entrenched in a misogynistic world of self-pity and excess. While Gatsby throws the extravagant parties, he does not himself attend, and upon his death, his funeral draws few mourners. Nick and the male characters spend their jealous days vying for the affection and attention of women who invariably disappoint. Debauchery, adultery and domestic abuse, car crashes, mistaken identity and murder/suicide—the life of the excessively wealthy doesn’t seem to produce anything beyond superficial and temporary enjoyments.

The Godfather, Mario Puzzo (1969)

Michael Corleone, born into the most powerful mafia family in New York City, is tasked with running the family business with his brother Sonny when their father Vito “Don” Corleone is shot. Taking it upon himself to murder the man who shot his father, as well as a corrupt cop, Michael’s impulsivity and abuse of power leads to an all-out mob war. Sonny is killed, paving the way for Michael to take over as head of the family, despite his immaturity and aversion to participating in mafia business. He is handed the keys to an empire, complete with unearned respect, influence and control, and the result is a torrential blood bath, culminating in the sale of the family business, and relocation to Vegas. It is, truly, lonely at the top.

Bright Lights, Big City, Jay McInerney (1984)

Already steeped in delusion and self-pity, the narrator drowns his sorrows in the Manhattan party scene and cocaine. He works at a magazine where he wanted to be a writer but was hired as a fact-checker, and he sees the life he wishes for himself on a daily basis. Jilted by his model wife, he is left in shame, covering up the fact that she’s divorcing him, and falling deeper into his disenchantment. A more thinly veiled, if veiled at all, portrayal of the sad realities of the glamorous Manhattan life. In keeping with the second-person narration: your best friends aren’t your friends, you don’t know what you’re doing or where you’re going, and you’re sure, absolutely, that someone else it to blame.

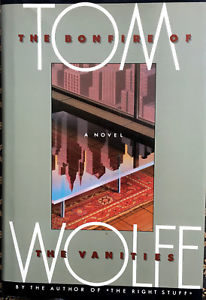

Bonfire of the Vanities, Tom Wolfe (1987)

Sherman McCoy, top-tier Manhattan bond tradesman is living the life of a typical “Master of the Universe”: multi-million dollar Park Avenue apartment, Hampton’s weekend home, both a wife and a mistress dripping with jewels. McCoy and his mistress zigged when they should have zagged and found themselves in the what they would perceive as the wrong part of town. Trying to escape two would-be assailants, they end up killing one of them. Plummeting into a sea of racial injustice, political posturing and corruption, Sherman and a cast of loathsome, albeit amusing characters navigate his journey to ruin.

***

Youth, extravagance, wealth and beauty, our society still heralds these as the most desirable features of life. We don’t often associate the elite with guns, drugs, vehicular manslaughter and a seething sense of discontent. As told in these novels, the male anti-heroes aren’t fulfilled or even comfortable, and are often hiding a heartbreaking or psychotic truth beneath their shiny surfaces.

Themes of loneliness and jealousy are woven through these novels, disappointment and lack of satisfaction with one’s station despite being so high above the masses. Whining, complaining, exceptional levels of self-pity and entitlement, murder, depravity and drugs—the truth underlying the “don’t hate me because I’m beautiful” set. It’s hard to love them, it’s hard to identify with them, but in the end, if we aren’t envious of their riches, their good looks and possessions, if we can see through their self-pity and appalling behaviors, we can find ourselves feeling for them. It’s a sad life—pleasing the unpleasables—it seems impossible to satisfy the semi-grown men born from the soft white underbelly of New York City privilege.