Leo Tolstoy, author of my favorite novel, War and Peace, said that the purpose of art is to teach us to love life, an observation that has pleased me since I first read it.

But on reflection, I think it fair to say there are other things that art can do in relation to life; it can change the way we see life; it can teach us to endure or perhaps enable us to escape life. For a time, anyway. In a world beset by unprecedented horrors, where the survival of the planet itself seems to hang by a fraying thread, art can sometimes grant us respite—time, as it were, to catch our breath. Art can take us out of ourselves, plunging us, however briefly, into alternative worlds, worlds of beauty and make believe, worlds that allow us a pause from day to day anxiety and panic, a “timeout” in which to… surrender to enchantment, to collect ourselves so as to return refreshed and perhaps inspired to resume the ongoing battle with reality.

The art that can accomplish this may not necessarily or always be great art. It might be. It might be Mozart or Shakespeare, which for me is akin to getting a transfusion. But it could also be the less exalted variety, like, for example, the satisfaction of curling up with a good mystery story at bedtime.

Detective stories, are, as many will allow, a source of great comfort, which is strange if you think about it. After all, detective stories promise death and bloody destruction, serial killers, and mayhem, severed body parts with corpses splayed at unnatural angles, the skulls fractured by blunt instruments wielded a person or persons unknown. How can this stuff be comforting? Because detective literature for all its protestations of thrills, gore and procedural authenticity, frequently delivers the exact opposite of what it promises. Unlike life in which dreadful things happen for no reason, where children are struck by lightning or pedestrians by drunk drivers, in detective stories, as the gumshoe sooner or later observes, “it all adds up.” In detective literature, unlike life, nothing happens without a reason.

So yes, we love detective stories because they help us escape real life. It is a superficial escape, to be sure. It isn’t a total transfusion like Mozart, (who has unfortunately been elevated to a form of castor oil—“listen to your Mozart, it will make you smarter!”) Detective stories by contrast are what some people call guilty pleasures. And let’s admit frankly that some pleasures are all the keener because they’re guilty. We feel we should be spending our time on more “worthwhile” things, but we cannot resist the siren call of, “Come, Watson, the game’s afoot!”

Artists lose all proprietary authority over our creations when they’re finished. We cannot be objective judges of our creations. Like Moses, we don’t get to cross the Jordan and look back to see the trail we’ve blazed. Like messages stuffed in bottles, our work is essentially thrown out into the wide world, hoping for the best. Each person who extracts the message within will make of the contents what they will. So, what follows must be counted idle speculation.

I write Sherlock Holmes stories for the same reason I read them, to divert my attention from the terrifying issues that plague the rest of my waking hours—Ukraine, Gaza, drought, famine, wildfires, limits on voting rights, Fox News and anti-vaxxers.

But for a few hours, when I read or write Sherlock Holmes stories, I am transported to what appears to be a simpler world, where a creature of superhuman intelligence, nobility, compassion and yes, frailty, can make sense of it all. Was the Victorian world in fact simpler than this one? We’ve no way of knowing, but like an audience willing itself to believe that the magic trick is really magic, we are conniving accomplices to our own beguilement.

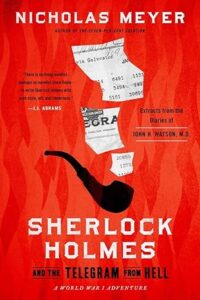

I’ve now written five Sherlock Holmes novels. The sixth, Sherlock Holmes and the Telegram from Hell, will be published August 27 and I am working on a seventh. I didn’t plan on writing more than one and I don’t write them unless I have an idea that seems right for Holmes. Ideas of any kind do not come easily or plentifully to me. As an example, twenty six years passed between the time I wrote The Canary Trainer and when I wrote The Adventure of the Peculiar Protocols. The idea has to be good enough so that it teases my brain and won’t let go. When I should be doing other things, grownup things—like earning a living—instead I am lying awake and riffing on what has begun taking shape in my head. I self-censor easily. If I can poke holes in my idea, it becomes natural if not inevitable that l lose interest and drop it.

My novels fall into the category now pejoratively labeled “pastiche,” which I confess I find irritating. All art is a history of cut and paste. Are James Bond movies with different Bonds also pastiches? Star Treks with different Spocks? As Michael Chabon has observed, all fiction is fan fiction. What are the Odyssey and Aeneid but fanboy spinoffs? There is something to be said for pouring new wine into old bottles. Don’t we sometimes get off listening to covers of The Beatles? Just to see what someone else does with their songs? Isn’t it cool to hear Sinead O’Conner’s riff on “Nothing Compares to You?” To listen to Tiffany’s version of “I Think We’re Alone Now”? The words of the Catholic mass are pretty standardized, but who would argue that Mozart’s “Requiem,” Bach’s “B Minor Mass,” Verdi’s “Requiem” or Haydn’s “Mass in Time of War” are “pastiches”? The music makes them different. Seeing what can be done with Holmes and Watson while adhering to the rough outlines set forth by Doyle, seems to me as legitimate a challenge as setting new music for the text of the “Dies irae.” No one confuses Mozart with Verdi.

Most of my ideas reach me indirectly; they begin as someone else’s; in however incoherent form, I trip over them. Or someone primes my thought pump. “What about Holmes and…?” and I’m off and running. Sherlock Holmes meets Sigmund Freud; Holmes in London’s theatre world; Holmes encounters the Phantom of the Opera; Holmes and the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. Lately, Holmes in Egypt. This last notion was no more than those three words. It was all I needed.

I find that taking Holmes out of his element (England, and specifically London), making him in effect, a fish out of (Thames) water, allows my creative juices to flow. I am not interested in limiting myself to Doyle’s vocabulary or never allowing Holmes an action that he hasn’t performed earlier someplace. Mere variations along those lines strike me as inevitably a species of taxidermy. I know it sounds counterintuitive, but in my opinion in order for Holmes to come to life he must change. But he must always change in character.

It is a fine and arguably abstract line that I am drawing and while I’ve no doubt there are Doyle imitators who successfully adhere more literally—and literarily – to Doyle than I do, I am not certain the results are more lifelike. Of course, I’ve not read many other Holmes novels and stories, for two reasons: firstly because there are now so many that if I attempted to canvas the competition I’d never have time to read anything else. Secondly, I shy away from other Holmes books, not because I suspect they might be dreadful but because I am just insecure enough to fear they might be better—much better—than my own attempts. I’ve read some that are and the result is a kind of brain freeze wherein I become creatively inhibited. Or worse, I start to imitate other Doyle imitators.

Writing Holmes, of necessity, involves an enormous amount of research. Whether it’s a novel or a screenplay, entering a different narrative milieu is like starting medical or law school. You write down everything because you’ve no way of judging at the start what will prove pyrite or gold. You go for long walks, notebook in hand. You think about possibilities as you fall asleep and as you wake. You try things in different combinations. Somehow the result must seem inevitable, one event leading to inexorably to the next. Besides our dynamic duo, who are the characters? What are Holmes and Watson doing in Egypt? In Russia? What is the mystery? (Hint: a body always helps). How much description can the reader (used to moving pictures in all venues) tolerate? How much modern and how much ancient history do you—and the reader—need to know in order to follow the story? How much information is too much? Research is like painting stage scenery. All you need is what you want the audience to see, not what’s hidden in the wings, fascinating though it may be.

It’s like fiddling with a Rubik’s Cube.

But it is more than that. For all the research, the hesitations, the false starts and frustrating stops, it cannot be denied that writing a detective story provides—for this author, at least—many of the same pleasures as reading one. It is, in short, a great escape of its own. And, to mix a metaphor, it can only be hoped that my great escape proves contagious, that what I stuff into my bottle will entertain and divert those who chance upon it.

__________________________________