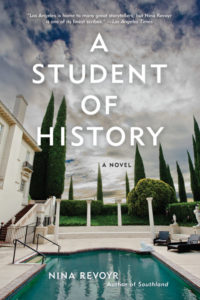

Any Nina Revoyr novel is a cause for celebration, and her latest, A Student of History, is assured and marvelous, an absorbing rags among riches tale about a broke USC grad student who finds himself swept off his feet by Los Angeles’s insular, powerful .01% class. It’s a contemporary novel that feels like an instant classic, with the wry tragedy of The House of Mirth, the sinister glamour of Sunset Boulevard, and a fresh, original point of view. I spoke to Nina over email about her new book and money and power in Los Angeles (yes, I asked her about the college admissions scandal).

Steph Cha: I think because I came to your work through Southland, I find myself approaching and evaluating your books with crime on my mind. A Student of History isn’t really a crime novel, but honestly, it’s not not a crime novel either. Were you thinking about it in these terms as you were writing it?

Nina Revoyr: I was thinking more about the archetypal stories of class, like The Great Gatsby and Great Expectations. I probably also had a bit of Sunset Boulevard on my mind, particularly in how Mrs. W— dresses Rick in expensive clothes. But I do always try to create a sense of momentum, a sense of “what will happen next?”—whether in books that have structural elements of mystery, like Southland or The Age of Dreaming, or books that build up to a climactic event or resolution, like Wingshooters or Lost Canyon. Story matters, entertaining the reader matters, especially if you’re dealing—as I do—with issues of race and class and history, which can feel weighty. Once Rick volunteers to help Fiona Morgan make sense of an incident from the past, he does become a sort of detective. I’d argue, though, that even Gatsby and Great Expectations deal with mystery, as well as crime—crimes that are covered up, or crimes that make the central action possible.

I feel like your book has suddenly become even more topical thanks to the recent college admissions scandal. Your protagonist Rick Nagano is a graduate student at USC who becomes fascinated with the world of ultra-rich old money Los Angeles when he takes a job as a research assistant for Mrs. W—, an oil heiress. Money is one of the primary concerns of the novel, and certainly of Rick, who tells us he’s broke in the first line of the book. Can you talk about money and what it can buy in Los Angeles? And what do you think of the current scandal?

Yes, the timing of the admissions scandal is uncanny! At different points in the book, both Mrs. W—and Fiona offer to intervene with the president of USC, in one case to help with admission into USC’s law or business schools. Rick is taken aback by this, but it underscores—as does the current scandal—that people of great privilege have access and influence that the vast majority of us don’t have and couldn’t imagine. It doesn’t even occur to Mrs. W— or Fiona that their influence with USC and other institutions—which comes from their historic ties and of course their donations—is questionable or unfair; it’s just the way they operate.

Rick, of course, comes from a different world: his father and grandfather were both electricians, and he’s the first in his family to go to college. On the one hand, his own status is different because of his fancy schooling. On the other, he will never enter a certain strata of society—and that would be true even if he pursued a more lucrative career. Part of what he discovers in interacting with Mrs. W— is that class isn’t just about money, but also about lineage and history. People who make fortunes through tech or finance or entertainment might be able to buy their way into USC or onto certain boards, but money can’t buy the kind of status enjoyed by Mrs. W— and her crowd.

As for the real-life admissions scandal, a few things strike me. First, the whole thing underscores how much kids from working class and low-income families have the cards stacked against them. Second, it’s worth noting that wealthy parents not only gamed the system but enlisted their kids in the effort—that they instructed them, shamelessly, in how to gain advantage. Third, I’m surprised that anyone is actually surprised by this. The particulars may be new, but the dynamics are so prevalent—which is why I could create a story in which people behaved similarly.

Of course, money is just money, and the world of Mrs. W–– isn’t open to anyone who hits some minimum level of wealth. Rick, who is half Japanese and half Polish, is often the only non-white person at the party who isn’t wearing a uniform. A Student of History is part of a tradition of novels about working-class people who long for wealth and status, but I can’t think of another book I’ve read in this subgenre that deals effectively with race and class at the same time. Can you talk about how Rick’s ethnicity colors the dynamics of this novel?

I’m glad you brought this up, because the interplay of race and class is something I really wanted to tackle. There are at least a couple of layers for Rick—his own racial background, and also the neighborhoods where he and his family have lived. He grew up in Westchester, a racially mixed, then-lower middle class part of L.A. that’s right next to the airport, which has recently been transformed by new tech money. And his parents grew up in Crenshaw—the largely African American and Japanese American neighborhood featured in Southland. He still lives in a gritty part of South L.A., near the USC campus, next to his old high school friend Kevin, who’s African American, and Kevin’s Dominican girlfriend. So Rick hails from polyglot areas that represent, to me, of the best of Los Angeles. And then he finds himself in this very exclusive, almost archaic world that’s not only wealthy, but entirely white; within a set of people who want for nothing and who have no doubt about their own relevance. In these folks’ presence, he’s self-conscious about his modest beginnings, and he admires and envies their privilege. And all of that longing gets wrapped up together in the form of Fiona Morgan. She and her friends sexualize him—or pretend to—but it’s in a condescending way that also makes clear that he’s “the other.” He becomes a kind of mascot for her, and she uses him—as she would any form of “the help”—to get what she needs. But Rick is not simply an innocent victim, either. In his desire to win Fiona and to achieve some sort of status, he willingly overlooks these dynamics. And ultimately that—and his distancing himself from his background—comes back to bite him.

Rick’s voice feels so natural and consistent throughout the novel that I would almost believe that you wrote this whole thing without even needing to edit. That is…wrong, right? Can you talk about how you nailed Rick’s voice and characterization? He just strikes me as an incredibly real character, someone I can imagine walking around Los Angeles, living a different story.

Thank you, and believe me, I had to write, re-write, trash, and edit many times. I wrote this novel over the course of a decade, and had several false starts. Always the original premise was there—the idea of Rick getting a job as a research assistant for a rich lady—but I didn’t know what the story would be, who was in it, or what was at stake. It took growing up a bit to fully understand him, even though he’s younger than me—and to understand the world he was moving in. And it was a challenge to sustain his voice—which is a bit wry, a bit self-deprecating and maybe self-deluding—and to have him make some questionable choices while hopefully remaining sympathetic. I’d keep going back to the first paragraph, the first couple of pages—which stayed pretty much consistent—and try to create that same point of view, that same voice. I’d also say that there’s quite a bit of me in him, although I like to think I’m markedly less clueless. And I have a different relationship, of course, to my own racial and class background—a sense of pride in the things and people that made me.

I saw you speak about A Student of History at Skylight Books, and you mentioned that Mrs. W–– was your favorite character. I love Mrs. W–– and was impressed with your portrait of her. Where did she come from? How did she develop as you were writing the book?

She’s definitely my favorite character! She’s full of contradictions—on the one hand, she’s snobby and misanthropic and can say outrageous things, and she obviously uses her wealth for some questionable ends. On the other, she’s generous and kind in ways she goes out of her way to disguise. I wanted her to seem larger than life to Rick, to be both intriguing and out of reach—and if anything, he ultimately underestimates her complexity. I’ve met a number of really fabulous, wealthy older women over the years, some who’ve taken their privilege very seriously, some who’ve been comfortable poking fun at themselves or who’ve knowingly used their fortunes for good. Several of them influenced the crafting of Mrs. W—. And in terms of how she developed as a character—I grew more and more sympathetic to her through the course of writing the book, not least because of Rick’s ultimate failure to recognize her humanity.

You spent a lot of your career as an executive of Children’s Institute. I’m guessing you’ve been to your fair share of fundraisers around town. Is that where you observed this hidden layer of mega-rich Los Angeles? I grew up going to private schools in L.A., but I feel like this world is opaque even to me. It’s so interesting, it feels so old world and un-Californian.

I definitely met my fair share of the mega-rich during my work at the non-profit—as does anyone who’s dealt with fundraisers for big nonprofits or institutions in town. But my first real contact with old money came when I went to college at Yale. Coming from a modest background, it absolutely blew my mind to see kids who spent money with no care in the world; to meet descendants of families I’d only read about in history books; to hang out with students whose families owned islands. But yes, the kind of world depicted in this book does feel antithetical to L.A.—which again, at its best, is the meeting place of so many people and cultures; is a place of reinvention for immigrants and migrants from other parts of the country alike; is a place where civic activism and organizing, especially in communities of color, has led to so much change and good.

That said, this is a very Californian novel, most of it set in Los Angeles, with a couple important forays to the Central Coast. Where do you see this secretive hyper-wealthy world fitting into the broader ecosystem of L.A. and California?

The Central Coast is definitely an important part of this book, and it was great fun to explore that landscape in writing, as well as the Central Valley. Both of those vast spaces help emphasize the impermanence of humans—even as they bear the marks of our activities. As for how the world in this book fits into the broader ecosystem, I think its important to recognize that this separate world of privilege—both in L.A. and more broadly—is real, and continues to influence the workings of our city and country today. It plays out—just as it has in the last few weeks—in who gets access to what kinds of schools and institutions, not to mention professions. It plays out in laws and policies that favor the privileged over the struggling. That means that those without such access—which of course is the vast majority of people—need to work twice as hard, and that we also have to watch for ways that systems and structures are stacked in certain people’s favor.

It would’ve been easy for you to lampoon everybody in this book, but you really don’t do it at all. If anything, there’s a current of sadness that seems to unite a lot of your characters, even if only thematically. Was this difficult to pull off, or does this level of empathy come easily to you?

As both a writer and a human, I try to understand where people are coming from—and to understand what went into their making. If I had just made fun of these characters, that would have been way too easy. Mrs. W—, for all her wealth, is also dealing with disappointment and sadness—she lost her husband young, and is estranged from two of her kids. It’s this loneliness, of course, that contributes to her attachment to Rick. And Fiona has a story too, which we learn eventually. But even besides that, she’s an intelligent woman who doesn’t have to work, and there is probably some frustration and boredom in that, in not fully using her education and talent. Their wealth removes them from some everyday problems, but it doesn’t spare them from the human condition. For me—in this novel as well as in life–being rich in itself isn’t the problem—although we do need to reflect on a society that allows for such incredible inequality. The problem for many of these characters is that they put their wealth and privilege above all other concerns—that money becomes their master. Even Rick becomes susceptible; he gets too focused on money and status. He doesn’t see that the most admirable rich people he encounters—Mrs. Randall, Mrs. W—’s son Bart, Mrs. W—’s grandfather Langley—either don’t make a big display of their wealth or consciously use it to benefit others.

What are you writing, and reading, now?

I’m in the very early stages of something new, too early to talk about. And in terms of reading, I just finished Susan Choi’s My Education—an unexpected and tortured love story—for the second time, and am starting her new one, Trust Exercise. After that is Nicole Dennis-Benn’s new book, Patsy—about a Jamaican immigrant who leaves her family behind to pursue her secret love in New York. And when I need a break from fiction, I’m dipping into David W. Blight’s glorious biography of Frederick Douglass, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. For lighter fare, I admit that I sometimes seek amusement on social media. My favorite Twitter handle for this purpose is one you should know about, if you don’t already: “Thoughts of Dog,” @dog_feelings. It never ever fails to make me smile.