Whenever I receive the tried-and-true question—“Where do you get your ideas?”—I answer honestly: “A lot of the time I steal them from myself.”

By this I mean, as a veteran journalist (a decade in newspapers and more than twenty years now with The Associated Press), I have plenty of material at my fingertips. For sure, I often study up on plotlines and scenarios for my mysteries about Andy Hayes, a former Ohio State and Cleveland Browns quarterback turned investigator in Columbus, Ohio. But more often than not, I’ve already done much of the preliminary research through my reporting.

In my first novel, for example, one of the characters works at a shady healthcare financing firm. To create that fictional corporation, I looked no farther than the five weeks I spent covering the 2005 trial of executives with National Century Financial Corporation, a suburban Columbus-based company accused of running an elaborate Ponzi scheme with investors’ money. With $1.9 billion in losses, it’s considered the country’s largest private corporate fraud scheme, on par with cases involving publicly traded firms like Enron and WorldCom. My second novel, Slow Burn, was based loosely on the still unsolved arson that killed five college students—three Ohio University students and two Ohio State students—at an off-campus house in Columbus in 2003. A suspect was arrested briefly but then released in that case. Twisting the narrative, I conjured up a defendant who was easily convicted, but in fact might be innocent.

Over the years, I continued to draw inspiration from my reporting, whether covering politics at the Ohio Statehouse, writing about human trafficking and its victims, or interviewing the armed vigilantes who in 2015 showed up uninvited outside a military recruiting office to “guard” the personnel inside, following a shooting at a recruiting station in Chattanooga (my novel The Third Brother used that latter incident as a jumping off point).

My new book, An Empty Grave, just released by Ohio University Press, uses as a launching point the story of Niki “Nick” Cooper, a Columbus police officer shot in 1972 during an armed confrontation with a burglar, who was also wounded. For reasons that are still unclear, the burglar escaped prosecution and eventually, after committing other crimes out of state, was found in 2016 living a quiet life in Dayton. A judge ultimately ruled that the window for prosecuting him had closed, devastating the family of the officer, who had waited decades for justice. In my retelling of the case, it’s up to my private eye to find the unprosecuted burglar, who may or may not still be alive.

Crime novels based on or inspired by real events are hardly new. The 1922 murder in London of Percy Thompson by Frederick Bywaters, the lover of Thompson’s wife, Edith (both Bywaters and Edith Thompson were convicted and hanged), inspired several novels, including F. Tennyson Jesse’s A Pin to See the Peepshow. Josephine Tey’s 1948 novel, The Franchise Affair, about a mother and daughter’s alleged kidnapping of a teenage girl in post-World War II Britain and considered a classic in the genre, was based on a non-fiction account of a real-life 18th-century case of a maidservant’s abduction. In The Black Dahlia, James Ellroy retold the infamous 1947 Los Angeles slaying of Elizabeth Short, the woman whose mutilated body was found in an abandoned lot. Similarly, Margaret Atwood based her Alias Grace on Grace Marks, a poor Irish-Canadian immigrant convicted in 1843, of the double murder of her employer and his mistress. Novelist Joyce Carol Oates has incorporated real events in several works, including Black Water, a 1993 Pulitzer finalist inspired by the 1969 death of Mary Jo Kopechne on Chappaquiddick Island as she was a passenger in a car driven by Sen. Ted Kennedy.

Critics might argue that this approach is cheating, with writers simply cutting-and-pasting reality onto the page and then covering it in a veneer, thick or thin, of fiction. They might have a point where a paint-by-numbers roman à clef is concerned, in which literally nothing more than names are changed. In that case, it might be better to stick to a true crime approach, which has become an art form itself in recent decades through the lens of narrative nonfiction. Look no farther than Peter Houlahan’s 2019 book, Norco ’80: The True Story of the Most Spectacular Bank Robbery in American History, to see the literary heights that this approach can reach. But when it comes to fictional retellings, though the usual expression is “art imitates life,” the art often elevates reality as well. As we see time and again, the literary realm provides an opportunity to explore the histories, motives, and emotions of characters involved in crime that can fill in gaps—and answer questions—left blank in reports and witness accounts, no matter how detailed, of a violent incident and its victims.

Here are nine books with plots pulled from real life, expanded and turned, like straw into gold, into an altogether new creation.

To Die For, by Joyce Maynard

Maynard’s 1992 novel and a subsequent movie starring Nicole Kidman took their inspiration from the 1990 New Hampshire case of Pamela Smart, who was convicted of coordinating the murder of her husband with her fifteen-year-old high school boyfriend. Smart was accused of telling the boy she would stop having sex with him if he didn’t carry out the murder. Maynard wrote that she used, “in a novelistic way, those facts made known to me through television and newspaper reports. But when those facts contradicted my imaginative and fictional necessities, I chose to pursue my own imagination.” The Pamela Smart case was also the subject of several true crime books.

What The Dead Know, by Laura Lippman

A woman arrested for leaving the scene of an accident confesses to police that she is Heather Bethany, a girl who disappeared with her sister from a local mall in the 1970s, a case that until that moment was never solved. Lippman based the book on the real-life disappearance of sisters Katherine Mary Lyon, 10, and Sheila Mary Lyon, 12, from a mall in Wheaton, Maryland, in 1975. (Though the girls’ remains have never been found, a career criminal finally pleaded guilty to their murders in 2017). “We were raised to believe that we were safe going out in pairs, and the fact that two girls went out and never came home seemed particularly haunting,” Lippman told NPR in 2007.

The Art Forger, by B.A. Shapiro

The March 18, 1990, theft of thirteen works of art from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston is one of the most infamous art heists of all time, as two men disguised as police officers bound and gagged two security guards and then removed the art. While numerous suspects have been identified over the years, none of the art—including five works by Edgar Degas—have been recovered. Shapiro uses the theft as the jumping off point for a literary thriller about the mysterious appearance of one of the Degas paintings in a young artist’s studio, and the secrets the missing work may contain. Shapiro says after years of thinking about a novel focusing on Gardner and the theft, the inspiration finally came when she considered one question: “What would any of us be willing to do to secure our ambitions?”

Deadly Harvest, by Michael Stanley

The writing team that is Michael Stanley—Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip—chose one of the more horrific crimes in recent African history as a jumping off point for their 2015 book in their series about Botswana Inspector David “Kubu” Bengu. In 1994 a girl named Segametsi Mogomotsi was killed in the Botswanan village of Mochudi in a muti murder, or the witch doctor practice of killing people for body parts to be used in potions. No one was ever charged. In the novel, characters express fear at revealing the identity of a witch doctor involved in such activities. “But you know it happens,” Kubu counters. “And unless we stop it, unless we find the few witch doctors who commit such terrible deeds, it will never stop.”

Quiet Dell, by Jayne Anne Phillips

The real-life tale was chilling: Asta Eicher, a widowed mother of three in Chicago during the Depression, was taken in by letters sent by Harry Powers, a Dutch-born American who specialized in preying on—and ultimately killing—women he lured through “Lonely Hearts” ads. Phillips recreates events leading to the murder of Eicher and her children based on actual characters along with a few, selective inventions, including fictional journalist Emily Thornhill, determined to see justice done. Thornhill is an homage to Phillips’ mother who, she writes, first told her of the murders in Quiet Dell, West Virginia, walking her past the crime scene, “a dirt road in the hot sun, lined with cars on both sides as far as I could see, and people taking the place apart piece by piece for souvenirs.”

An Unsettling Crime For Samuel Craddock, by Terry Shames

In August 1992, a man named Anthony Graves was arrested for the slaying of a family of six in Somerville, Texas. He spent eighteen years behind bars before he was exonerated of a crime he didn’t commit. Shames uses the incident as the basis of this prequel novel to her series about Craddock, chief of police in the fictional town of Jarrett Creek. In the book, Craddock investigates the death of five people and must overcome a racist investigator’s belief that a Black man committed the murders. Shames said the crime “had been in my mind for a long time as the basis for a story.”

Girl Waits With Gun, by Amy Stewart

The true story of Constance Kopp, the first “under sheriff” in the United States (appointed in 1914 by Sheriff Robert Heath of Hackensack, New Jersey) inspired Stewart’s novel and several sequels about Kopp. Although Stewart created some characters and took liberties with real individuals, she also extensively researched Kopp’s history and interviewed descendants of people from the era. “My task as a writer was to take the public record—pieced together from newspaper articles, genealogical records, court documents, and other sources—and invent the rest of the story,” Stewart wrote in her afterword. She plucked the novel’s engaging title from an actual Philadelphia Sun headline that ran over a story about Kopp on November 23, 1914.

Your House Will Pay, by Steph Cha

Multiple painful secrets and personal histories are exposed in this moving novel about the impact of the murder of a Black teenage girl in Los Angeles immediately before the Rodney King beating. Cha, author of the Juniper Song amateur sleuth trilogy, based her book on the March 16, 1991 killing of fifteen-year-old Latasha Harlins by Soon Ja Du, the woman who owned the convenience store where Latasha had gone to buy a bottle of orange juice. Soon Ja Du was convicted of voluntary manslaughter but received no jail time. Cha moves her 2019 novel back and forth in time and tells the story from the perspective of both the girl and the woman’s families, in a powerful reflection on race, violence, family and love.

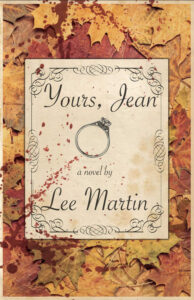

Yours, Jean, by Lee Martin

Martin’s book narrates events leading up to the 1952 murder of Jean De Belle, the new high school librarian in Lawrenceville, Illinois, by her ex-fiancé, and then follows the impact of that event on multiple characters. The story was inspired by the real-life slaying of Georgine Lyon in Lawrenceville in a high school English classroom, and includes several details lifted from the case, such as killer Charles Petrach’s hearing loss from serving on an Army demolition team, and his arrival in Lawrenceville via taxi to confront Lyon about breaking off their engagement. Martin’s book is a classic example of taking such details and then creating exquisitely drawn fictional character studies of the people whose lives were touched by trauma. Martin, who grew up near Lawrenceville, wrote much of the book during visits home. “The crime is true; the rest is pure imagination,” he wrote in the acknowledgments.

***