Successful authors have a personal brand. This is advice I’ve received a lot: make sure that when someone sees your name, they have a good idea what they’re getting. That’s the way to find and cultivate an audience.

It’s advice I’ve followed very badly. My output in the last few years alone includes science fiction novels, a contemporary rom-com for Audible, preschool cartoons and a spoof true-crime podcast for kids. But to me the interplay between genres is fascinating, and that’s why I love working in different ones. Genres don’t exist in isolation: whatever label we put on something to help it find its audience, there are always blurred boundaries, tropes to be borrowed and subverted.

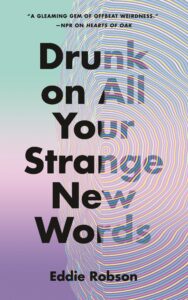

My latest novel, Drunk on All Your Strange New Words, is both SF and crime. This isn’t at all unusual, of course: those two have been combined many, many times, in forms ranging from The City and the City to Judge Dredd. SF texts are very often hybrids anyway, because the big genre markers of SF provide settings and themes but don’t necessarily give you story. If it’s set on a spaceship it’ll be labelled SF, but the story could be romance or political thriller. However, there’s a fundamental connection between SF and crime because they come from the same place: Gothic.

We tend to think of SF as being a future-facing genre, which seems at odds with Gothic, with its sense of decay and anxieties about the past. Yet the root of SF is generally agreed to be one of the great Gothic novels, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—a text that imagines what science might achieve, and the ramifications if that came to pass. It invented SF tropes we’re still using today because they continue to work.

Some have argued Frankenstein is also a crime novel, and it’s a compelling argument: Victor Frankenstein spends a chunk of the novel as detective, tracking his creation. And other key texts in the development of the detective novel as we understand it today—the stories of Edgar Allen Poe, The Woman in White, The Hound of the Baskervilles—are also Gothic. There are even elements of the detective novel in Dracula, as the protagonists piece together Dracula’s background and follow his movements.

Dracula offers up a contrast between the old, dark, superstitious world represented by Dracula and the modernity of our heroes, who use trains and portable cameras and gramophones. They’re people of rationality and technology—both common features of crime and SF as they developed away from Gothic in the 20th century. The police procedural frequently emphasises psychology and forensic science as tools to solve mysteries and restore order, while SF is fuelled by the possibilities of technology, whether celebrating or warning against it. Yet the Gothic always comes back—that’s just what it does—and it has never truly left SF or crime.

I have a long-standing fascination for the noir school of crime fiction, and in fact I wrote a book about film noir where I made the case that noir and Gothic have always been close cousins. You can see this in noir’s fatalism, paranoia and fear of the past, as well as its peculiar claustrophobia: there’s a whole subgenre dubbed “nightmare noir”, springing from the work of authors like Cornell Woolrich. The Gothic element of noir I’ve always particularly enjoyed is the sheer knottiness of many of its plots, where events can seem inexplicable, creating their own disorientating effect on the protagonist—and the audience.

Meanwhile in SF we can look to the work of Philip K Dick, so often marked by ambiguity and uncertainty, calling into question the nature of reality. Technology’s increasing ability to create artificial things not only returns us to the territory of Frankenstein, it also brings back the essential Gothic quality of the uncanny. This became a familiar mode of SF in the wake of works like Neuromancer and Blade Runner—both of which, incidentally, also draw heavily on crime tropes. (Perhaps the most obvious, and successful, combination of all three is The X Files, which itself draws on key Gothic crime texts like The Silence of the Lambs and Twin Peaks.)

These are the strands of SF and crime fiction I was pulling on when I wrote Drunk on All Your Strange New Words. I wanted to write a crime novel where my protagonist—Lydia, a translator for an alien cultural attaché in a future version of Manhattan— struggles to even understand her own situation, and where chaos threatens to overwhelm her efforts to make sense of it. She finds herself assailed by constructed narratives enabled—and in some cases, wholly generated—by technology, which threaten to drown out the truth.

I also looked to noir for the type of detective I wanted to write. I’ve always liked stories where someone who isn’t a detective takes on the detective’s role—like Louise Welsh’s The Cutting Room or Rian Johnson’s film Brick. Someone with no official status to investigate, but who feels a moral obligation to do so, despite lacking the support of the police. I also liked the idea of my character being ill-equipped and lacking the relevant skills, and having to work all this out on the fly—I think there were shades of The Big Lebowski here.

All of this combined well with the book’s setting in a near-ish future. Detective novels are great for examining how a world works, because your protagonist has licence to talk to a range of people and find the connections between them. This means they’re also great for SF, where world-building is one of the main pleasures, but conveying this information to the reader can be difficult to do elegantly: the detective is an ideal character for this. But as I built this world, I quickly realized the challenge of setting a murder mystery in it.

Contemporary crime writers are already grappling with how mysteries work in a world rife with surveillance and data collection. Even a lack of information can now be a source of suspicion—a phone being turned off at a certain time suggests someone has something to hide. I was writing a story set about six decades into the future, and surely the reach of surveillance culture would, if anything, be greater. So how do you write a mystery that isn’t solved in five minutes flat?

Again I looked to noir. The classic nightmare noir scenario is waking up in a room with a dead body and having no idea how this happened, or even if they were responsible. So when the alien Lydia translates for is murdered, I decided to make Lydia the one who can’t account for her whereabouts, and in the absence of evidence finds herself the likeliest suspect. This gap in the data becomes a serious problem for her, making it all the more imperative she find out what happened.

And so Lydia is abruptly shifted from a science-fiction world where things make sense to her, to a Gothic world where she doesn’t know what’s going on and nothing makes sense. While I revel in switching between genres, the experience is a lot less comfortable for my protagonist, who probably wishes she was in one of those novels by writers who are better at staying on brand. I can only apologize.

***