Noir, both fiction and film, is built on a foundation of fear, and no fear grips us quite like the specter of our world ending at any second in a white-hot blast of nuclear fire. The Cold War had barely started when noir began using nuclear paranoia as a theme and a plot point—sometimes in subtle ways, sometimes as overtly as a shockwave destroying a town. Here are four movies and one book that exemplify the facets of what we might call “nuke noir.”

Notorious (1946)

Alfred Hitchcock began work on “Notorious” in 1944, more than a year before the first nuclear explosion at New Mexico’s Trinity Site officially kicked off the nuclear age. As pre-production on the film progressed into 1945, the director, who was interested in the theory behind a nuclear weapon, had the foresight to focus the script’s plot on uranium ore hidden in wine bottles by a group of escaped Nazis in Rio de Janeiro.

At the time, Hitchcock had no idea about American scientists’ work on a nuke, but his interest nonetheless earned him some special attention by the government. “When I went out to visit Dr [Robert Andrews] Millikan at Caltech with the writer Ben Hecht, we said, ‘Dr. Millikan, how big would an atom bomb be?’ and then he spent an hour telling us how impossible the whole thing was,” he said later, according to a transcript of a 1969 television interview. “But, I was told afterwards that I was under surveillance by the FBI for three months.”

As Hitchcock also acknowledged during that interview, the uranium ore could have been substituted for virtually anything else (diamonds, perhaps, or gold dust) and it wouldn’t have overly impacted the overall plot. Nonetheless, its presence adds a note of nuclear paranoia to what’s otherwise a well-mannered, often subtle thriller.

Stray Dog (1949)

Arguably Akira Kurosawa’s most notable crime drama, “Stray Dog” is a sweaty, twitchy crawl through Tokyo’s post-war underworld. Toshiro Mifune plays a detective whose pistol is snatched from his pocket on a trolly in the opening moments; as with all the best noirs, the situation escalates out of control, with a final standoff in a shadowy, misty forest that’s reminiscent of the samurai face-offs in Kurosawa’s later films.

“Stray Dog” and other Kurosawa noirs like “Drunken Angel” (1948) don’t deal with nuclear bombs directly, but they take place in a Japan still shuddering from the aftereffects of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Kurosawa constantly struggled against censors who were anxious to limit any overt critique of the American occupation, and yet he still managed to slip in imagery that hints at the war’s impact on the survivors. The consequences of a nuclear weapon aren’t just physical; the psychological and societal damage ripples for decades after the dust settles.

Split Second (1953)

As plots go, “Split Second” walks well-trodden ground: a set of bank robbers take hostages and hole up in an abandoned town. For much of its runtime, it plays like a 1950s drive-in version of “The Petrified Forest” (1936; Bogart, twitchy and armed) or a dozen similar films. But when the characters learn that the federal government intends to vaporize the town in a nuke test, it adds the ultimate ticking clock to the proceedings.

As you might expect, the climax plays more like a disaster movie, with a hefty undertone of existential dread: when confronted with the prospect of fiery annihilation, does anything—even love or justice—really matter?

The film’s director, Dick Powell, was a noir regular famous for playing Philip Marlowe in “Murder, My Sweet” (1941). He also directed “The Conqueror” (1956), the much-derided Genghis Khan biopic (starring John Wayne!) that was filmed downwind of a government nuclear testing site. Over the years, there’s been a fair bit of controversy over whether the site’s fallout contributed to Powell, Wayne, and other cast and crew dying of cancer. Whatever the case, it’s a spooky coincidence that a director who made a noir film featuring a nuclear test would possibly die as a result of filming another movie near a nuclear test site.

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Directed by Robert Aldrich (whose career included some all-time classics like “The Dirty Dozen” and “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?”), “Kiss Me Deadly” is notable for two things. First, it’s very loosely based on one of Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer novels; Ralph Meeker does a solid job translating Hammer’s vicious, somewhat wry mannerisms to the screen. Second, it hums with the Cold War tension that swept the country during the 1950s: everyone’s in pursuit of a mysterious box linked to a shadowy government project—a box that burns whoever touches it.

With a different MacGuffin in place of the box, “Kiss Me Deadly” might have been a competently directed but ultimately forgettable noir thriller. But as the action reaches a crescendo, one character decides to open the box, unleashing a minor apocalypse that plays like a memorable warning to anyone who feels a bit too blasé about the consequences of fiddling with the atom. (For film buffs, there’s another element worth your attention: some of the final shots seem like they could have influenced both the iconic suitcase opening in Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction” and the climax of “Raiders of the Lost Ark.”)

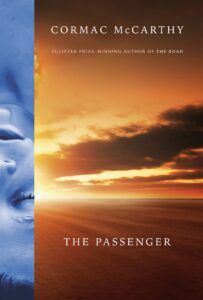

The Passenger (2022)

Let’s switch it up and offer a book: “The Passenger,” part one of Cormac McCarthy’s final two-volume opus, which you can argue is a noir thriller in literary robes. On the surface, the book centers on a salvage diver, Bobby Western, who finds himself pursued by shadowy figures after exploring a small passenger plane that crash-landed in the Gulf of Mexico.

As Western flees his pursuers, we learn that his father was involved in constructing the first atomic bombs at Los Alamos, and the novel digresses at several points into discussions of physics (and physicists) and the moral consequences of using nukes. “Auschwitz and Hiroshima,” Western muses, were “the sister events that sealed forever the fate of the West.” His father’s work in unleashing nuclear horrors may have sealed the fate of Western’s family, as well; the moral fallout wrecks Western and his sister, leading to their respective dissolutions.