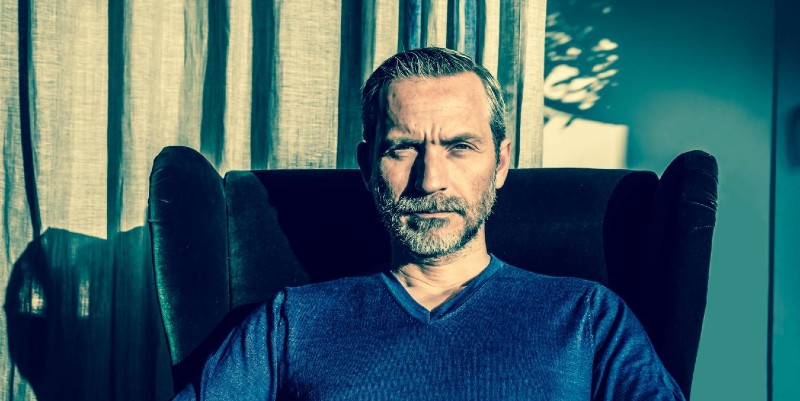

Welcome to the Paris of Olivier Norek, former French cop for eighteen years who reached the rank of Capitaine in one of Paris’s toughest banlieues (technically ‘suburbs’, but invariably indicating tough housing projects on the outskirts of major French cities). Norek has now turned crime writer but he’s still inhabiting those dark streets and criminal worlds.

Norek’s unfurling ‘Banlieue Trilogy’ (translated by Nick Caistor) takes place in Seine-Saint-Denis, a district of projects in the far from bucolic north eastern suburbs of Paris, and, according to France’s office of national statistics, the most impoverished area in the country—Seine-Saint-Denis is an official administrative French département number, the ninety-third and so known colloquially as the “93.” The banlieue is a stronghold of the “Red Belt” that rings Paris with a traditionally solid working class, immigrant, left wing heritage. Unfortunately, in recent years the 93 has become known for violent riots, while an estimated eighteen per cent of all drug offences in metropolitan France reportedly occur within the boundaries of the 93. The département’s dominating projects—‘wave after wave of tower blocks’— have become a largely economically bereft rust belt of the Île-de-France region all too often used as a dumping ground for Southern and Eastern European, North African, and Sub-Saharan African immigrants to France, leading to generations of long-term unemployed and impoverished young people. With few real educational or job opportunities locally, marginalised in the media and by the wealthy arrondissements of Paris nearby, naturally many denizens of the 93 have drifted into crime. The 93 is not “Le Tout-Paris” of that nice young Emily, or of the luxury stores of the Champs-Élysées, nor the Bohemian café-bars of the Sorbonne and the Left Bank. This is tough, raw, hard scrabble northern France. It’s devoid of glamour, style, or panache. And sometimes it gets a little wild.

In Norek’s novels Seine-Saint-Denis police are an insignificant satellite operation looked down upon, if indeed ever noticed, by the mighty Brigade Criminelle bedded down in central Paris at the Quai des Orfèvres, HQ of the Direction Régionale de la Police Judiciaire de la Préfecture de Police de Paris (DRPJ Paris). Its legion of “grands fromages” make decisions from on-high that create tensions and anger in the tower blocks. Political and social engineering decisions that mean life, death, budget cuts, or hassle for those who actually have to police Seine-Saint-Denis. And so, say bonjour to SDPJ.93 Groupe Crime 1.

Capitaine Victor Coste – driven, obsessive, emotionally damaged, hopelessly infatuated with pathologist Léa Marquant; new team member Johanna De Ritter who has to prove herself and fit in fast with a tight, introverted crew; the tough streetwise Ronan Scaglia; the techie and blood shy Sam; Lucien Malbert, disgraced former Vice officer, pulled out of retirement; and their boss Commandant Marie-Charlotte Damiani forced to eternally play politics while simultaneously trying to suppress the criminal elements and stop Coste pushing the boundaries of law enforcement a little too far.

The 93 isn’t high on anyone’s agenda – voting rates are notoriously low – you don’t win the Élysée Palace by pandering to the 93. In fact, quite the opposite. You have to look tough, appear to be doing something while knowing that the entire place is a powder keg that could blow up in your face and show images of burning cop cars on the TV news that make you look impotent and unelectable. So, resources are tight, manpower short, a queue at the morgue, flics with battered Peugeot’s on their last legs, and justice casually and unemotionally dispensed while politicians demand more and more. The banlieue of warring gangs are “deep cleaned” by armed rapid response divisions. “Poucaves” – snitches, apparently a term of Roma origin – are cultivated within the gangs and the tower blocks. Super alert “choufs” – lookout kids for the dealers – mean crowds soon come running when officers of the “brigade des stups” (drugs squad) show up, meaning they have to be rescued from the banlieue by the riot squad.

If all this sounds a little like the massively popular French TV show Engrenages (usually Spiral in English) that ran for a phenomenal eight seasons till finally ending last year, then you’ll recognise Norek’s style. He was an occasional writer on the hit series. Norek also served with the SDPJ.93, the unit that is at the heart of both Spiral and the Banlieues Trilogy.

The first in the series – The Lost and the Damned (MacLehose Press, 2020) – starts with the attempted murder, and successful castration, of small-time drug dealer Bébe Coulibaly, swiftly followed by the nasty murder of gang affiliate Franck Samoy. Commandant Damiani assigns the case to SDPJ.93 Groupe Crime 1. Capitaine Coste is a man of the “93”, outside Seine-Saint-Denis he seems slightly bewildered. Cross the eight-lane, always busy, Périphérique ringroad and enter the City of Paris proper, and the adjacent XVIIIe or XIXe arrondissements, and Coste is lost, recognising only the famous tourist sites and his usual destination, the Institut Médico-Légal de Paris, the city’s morgue, on the Quai de la Rapée. But he’s an infrequent visitor within the “Périph.” Coste’s world is deep in the “93” – Cité Gagarine – the Yuri Gagarin project (now demolished), the Commune of Romainville; the sprawling Roma camp in La Courneuve; a freezing cold-water squat in the suburb of Les Lilas; derelict warehouses of the homeless along the Canal de l’Ourcq. All less than five miles from the Eiffel Tower, yet seemingly light years from the boulevards of the capital. From the streetlights smashed to provide dealers with cover, the old fridges used to block the estate entrances to cop cars and, for this is still very definitely France, the solid metal Pétanque balls kept on the tower block roofs to rain down on the heads of the riot cops. And those balls come down alongside iron drain covers, paving slabs and Molotov cocktails as the riot cops fire sting balls, stun grenades and tear gas back into the projects. French riots are notoriously hard core affairs.

The Lost and the Damned is about the cops of the 93, but it’s also about the residents. All are lost – to the French state, to the justice system, to the wider French public – and all seemingly damned to suffer poverty, discrimination, and early death in the banlieue. This is a territory of all too often “invisible victims” – addicts, prostitutes, those “sans-papiers”, bodies never claimed by anyone, senior citizens trapped in their apartments afraid of muggers and broken elevators. But, of course, the world of Paris, high-level police cover-ups, corrupt government ministers, the wealthy boulevards, is never that far away (literally or metaphorically), and when it comes to paying for sex and narcotics the smart arrondissements of the bourgeois elites and the politically powerful, desire the services the denizens of the “93” are forced to provide. Worlds inevitably collide.

As they do again in the second instalment in the trilogy, the newly released Turf Wars (2021). The Malceny project is being taken over by new dealers – ruthless, violent, and (in stark contrast to the thuggish intellectual blunt instruments of their predecessors) smart. Old people, their pensions too small to allow them to escape the 93, trapped in tower blocks by broken elevators, their kids gone, friends all dead, are coerced to be stash-minders for the drug gangs. The young thugs that terrorise them adorn their apartment walls with posters of Tony Montana and the Godfather alongside posters for the movie biopic of Jacques Mesrine, their own home grown hero – bank robber, burglar, kidnapper, “The Man of a Thousand Faces” who eluded the cops for decades, was France’s “Most Wanted Man”, and escaped from the supposedly impregnable La Santé prison before being shot dead by police marksman in Paris – twenty rounds fired at point blank range – instant legend status assured.

Into this comes the local mayor of the 93. She’s managed to balance the gangs and the old folk, the Élysée Palace and the local media, by walking a fine, possibly corrupt, line. But that’s about to end when to her surprise the new kingpin of the 93 wants political power as well as control of the local drugs market. Capitaine Coste and his SDPJ.93 Groupe Crime 1 find themselves caught between investigating murders and drug dealing while trying to avoid getting caught up in the sordid mire of Paris city politics.

For my small stash of heroin residue-tainted Euros, Norek really gets deeper into the social structures of the 93 in Turf Wars, which has a more kitchen-sink feel than The Lost and the Damned. The third in the trilogy – yet to be translated into English but called Surtensions in French – will follow soon. All three books shine spotlights on the toughest of urban police beats in the banlieue, local and national politics in Paris, and the new forms of organised crime in France. That eighteen years Norek spent in the Seine-Saint-Denis is poured into the Trilogy in the form of numerous authentic asides and anecdotes (the technique of slip knot suicides, Yugoslav champagne thieves, Pakistani hitmen, cops who don’t take elevators as the kids jam them up), forensic, and crime scene detail as well as France’s apparently numerous criminal databases. And that time in the writing room on Spiral proved useful too – dodgy local mayors, boxing clubs as fronts for dealers, unconventional cops, all may ring a few bells.

Time spent in Norek’s 93 is certainly not time wasted. Good crime novels yes, with great characters, settings, and plot. But also voyages around worlds the French media often dismisses as simply zones of senseless violence, cess pits of drug trafficking, and breeding grounds for radical Islam. So it’s worth remembering that crime, drugs and riots are not all there is to the 93, or the banlieues across France. It also happens to be where many French soccer players, boxers, musicians and now increasingly film makers and artists hail from. But for Norek the 93 is Capitaine Coste’s world and he’s living it large.