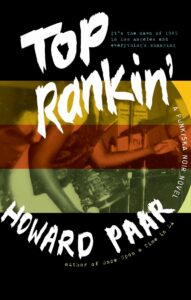

To come clean right out of the gate I had never intended to write about The On Klub days as I had no interest in writing a memoir, but when I finally did (at crime author Denise Hamilton’s behest), the only way I could imagine doing so was by way of a noir story: a memNoir, if you will. For me, the music business of those times, with its array of larger-than-life rogues, hustlers, and mob connected operators, lends itself perfectly to the genre. I’m so grateful to Denise as I had the best time writing Top Rankin’.

This approach allowed me to write with the intent of giving the reader an authentic, fun experience of 1980, lived in the moment, feeling the power of music in fast-changing and dangerous times. In my first novel, Once Upon A Time In LA, the protagonists were inside the music business, but in Top Rankin’, most of the characters are not yet in the business and are just trying to make it out of the 70s in one piece while pursuing their music dreams.

I’d got my five-year-old first taste of Los Angeles P.I. crime stories from Roy Huggin’s brilliant 77 Sunset Strip TV series and the deal was sealed when I was ten, home from school sick, and my Dad left me several Raymond Chandler novels to read— along with Peter Cheyney’s first Lemmy Caution story This Man Is Dangerous.

When I first arrived in Los Angeles from London in 1977, it was not with the intention of staying forever. I was infused with the Clash’s punk inspiration to get up and do something with your life.

From the beginning anything seemed possible here. Even though I’d been music obsessed since early childhood, by then I cared little for what was coming out of Los Angeles. The shock of hearing constant Led Zeppelin, Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, and bands with geography-inspired names (Boston, Kansas, etc.) on the radio was horrifying after having just experienced the punk uprising in London. Ultimately it was the literary and cinematic noir history of Los Angeles that made me feel instantly at home and ultimately kept me there.

Stepping off the Freddie Laker jet straight onto a baking tarmac and outdoor luggage carousel felt like I might be back in the 1940s. Although in many cases run down, the architecture that felt hauntingly familiar from black and white films was largely intact then, although not for long in many sad cases. I immediately became immersed in the last years of the 70’s rock-and-roll Rainbow Bar & Grill, oozing decadence and fun, and the small but growing LA punk scene.

The friends I made, and most original punks, I believe, felt an affinity for noir in all its forms. The doomed outsider, the anti-authoritarian outlook, and the femme fatales made for a perfect match with our punk ethos. In a real-life context, the LAPD’s hatred of punks, tinged with traces of fear perhaps, gave us firsthand tastes of what we imagined our anti-heroes had to constantly contend with.

Even to me it seems hard to comprehend now, but if you think I’m exaggerating here’s a snapshot from 79/1980. I’m standing outside the Whisky with Jello Biafra before The Dead Kennedys show with English band 999, who came over on the heels of their UK hit ‘Homicide’. The line of kids around the perimeter of the iconic club had an equal line of armed-to-the-teeth LAPD standing next to each of them. It was so over the top it was almost funny.

*

At the dawn of 1980 everything felt like it was changing. Punks, dopers, and assorted miscreants played in the decaying homes of Golden Era stars like Errol Flynn. The once and future iconic Sunset Tower was a glorified crash pad where Iggy Pop was fond of diving out of his third story apartment into the pool far below. The middle class was leaving in droves fueled by post-Manson paranoia, crime and general decay, leaving the streets to the likes of us. They shouldn’t have bothered replacing the missing letter from the Hollywood sign as its absence was a far better reflection of Hollywood at the time. The playfully decadent, diverse art punk scene of The Germs, The Go-Go’s, etc. was under threat from the violent misogynistic South Bay hardcore scene.

After hearing the brilliant debut single ‘Gangsters’ by The Specials in 1979, released on their own label 2 Tone with its inspired punky reimagining of 1960s Jamaican ska and accompanied by potent social political lyrics, I’d been hell bent on starting a club. My idea was to mix the new 2 Tone artists with the music that had inspired them. Most of it dated to the mid to late 1960s, by which time London’s Jamaican population had grown to 200,000 in a decade—lucky for kids like us who would never have been exposed to the music otherwise. Adopted first by the mods and then skinheads, both Jamaican ska and later bluebeat were heavily influenced by American southern soul, so I was convinced that playing a mix of those sounds would work great on a dance floor.

The great thing in LA at the time was that the UK artists I loved were all coming to play in LA and, except for The Clash (who played The Santa Monica Civic), were most likely to do a night or two at the iconic Whisky A Go Go. Bands would do two shows a night—the early one would be when record labels and publishers invited all the press, radio people, etc. and the 11:30 pm show would tend to be more intense. When the Specials played for two nights in February 1980 their label had the Whisky painted in 2 Tone black and white check.

I went to all the riveting shows, and after seeing many kids in the crowd adopting the clothes and style of 2 Tone, I was even more certain a club would work. The worst thing was that in between bands at clubs like the Whisky some hippie sound man would play The Doobie Brothers or some such, completely ruining the mood of the night.

The opportunity presented itself in the form of a run-down hole in the hillside joint in Silver Lake. The Vietnamese bar and restaurant was on its last legs and the owner wanted to talk to me about doing a punk club, something I had no interest in doing at that point. I think he was so desperate that I was able to convince him my idea would work despite the fact he had never heard of ska music. We had about three weeks and no budget to get started. Friends who had grown up in LA told me most kids had never heard of Silver Lake and definitely did not know how to get there. The club was on Sunset Boulevard though so I figured all they have to do is head East right?

After furiously posting flyers advertising the first show in LA clubs, record stores, and boutiques for two weeks, we opened to a packed club. Within two months things exploded. There was at least twice the legal capacity most nights and kids were crawling up the walls looking for dance space. LA Weekly music editor Bill Bentley dubbed the joint “The House of Sweat.”

As opposed to the increased violence and open misogyny in the burgeoning hardcore scene, there was no fighting on the dance floor shared by Jamaicans, South Central kids, art punks, sharp-dressed Asian American girls, English escapees, mod kids on scooters from Orange County, and a growing number of Latino kids from the neighborhood, all united by the racially unifying vinyl they couldn’t hear on the radio—or anywhere else in LA for that matter.

If you are intrigued to know what happened next, or where the noir elements entered, Top Rankin’: A punk/ska noir novel will fill you in.

***