When The Bishop’s Wife, the story of Mormon bishop’s wife Linda Wallheim investigating a woman’s disappearance in her own ward, came out, I went to a few Mormon women’s book clubs in Utah. One of those readers asked me, “Why couldn’t you have had the bad guy be a non-Mormon?” I was taken aback, then laughed a little, sure she wasn’t serious. But she was. “I wanted the bad guy to be a non-Mormon,” she said. And I asked, confused, “do you think Mormons are never the bad guys? Don’t you watch the news?” But she thought that I, as a Mormon, should feel an obligation to write positive depictions of Mormons, in part because that is what a lot of fiction published by local Mormon presses does.

Mormon fiction, published by and for other Mormons, has historically struggled to depict Mormons as the villains. This is partly due to the narrative of the origins of the church as a religion that demanded enormous sacrifices from its “pioneers” and which was so threatening to the religious and social norms of the time that the founder, Joseph Smith, was martyred and then the rest of the Saints were driven out of Nauvoo, Illinois, forced to spend a brutal winter in Nebraska, and then had to leave the boundaries of the then-United States to create their own theological kingdom in Deseret Territory (which is now the state of Utah). The Mormon narrative is one of being persecuted, misunderstood, and being a fragile minority with no financial reserves. Whether or not any of these are true is up for debate, but it is part of the myth of Mormonism. We aren’t the bad guys. If it looks like we are, that’s because we’re being persecuted.

Mormon fiction, published by and for other Mormons, has historically struggled to depict Mormons as the villains.But the truth is that, sometimes, Mormons are the bad guys. Obviously, if you look at the statistics of the state of Utah, there are the same number of murders, robberies, assaults and batteries, on average, as many other states in the Union. I’d argue that the refusal to reckon with this reality sometimes leads Mormons to be susceptible to a high rate of affinity fraud. Some have even called Utah the fraud capital of the country. Believing that other Mormons, by the sheer fact of their belonging in the church, are righteous and incapable of being motivated by the desire to enrich themselves at the cost of others, makes Mormons easier to con. It also makes us less likely to report crimes to the police, in part because of embarrassment, but equally because of the desire to protect the reputation of the church—or just because we don’t want to hurt someone else’s mother/brother/cousin. We love our community, and it feels as if talking about criminals within it will make it less safe, though it is paradoxically the opposite that is true.

The new Netflix documentary “Murder Among the Mormons” came out recently to a huge viewership, mostly of non-Mormons who don’t expect any special depiction of Mormons as somehow exempt from crime and better than the rest of humanity. It is the story of the famous forger, Mark Hoffman, who was good enough to fool not only the leaders of the Mormon church, but a number of collectors in the world of coin collecting and document production in the 1980s. The house of cards began to fall when his financial needs demanded he produce more than he could reasonably do in a short period, and the press of time led him to murder.

All of this happened when I was a teenager, living in Germany my sophomore year in high school. It didn’t make international news, and until the Netflix movie, I had only pieced together what had happened from bits and pieces of related Mormon news stories that unfolded in my adult years. Watching the documentary, I found myself thinking about how much this was an affinity crime, with Mark Hoffman playing on the assumption of his Mormonness, his connection to the tribe. The series leads to the question: Was his success because he was such a good forger or because Mormons were less likely to suspect forgery than any other group? I’m not sure there is an easy answer to this.

I have a personal stake in these questions of why Mormons need so badly to believe in the goodness of our own people. My paternal line—the Ivies—are well-known bad actors of the frontier era, so much so that a friend of mine wrote a historical murder mystery (Eric Swedin’s The Killing of Greyjoy) in which several of them appeared. When I read the book and reminded him those Ivies were my grandparents and that one of my brothers was named after the man largely considered the instigator of the Black Hawk Indian war, he said, “Mette, those were really bad people you come from.” I tried to explain to him that many of my relatives will go on for hours about how our ancestors had been grossly misunderstood and unfairly blamed for things other people had done. It can be difficult to be Mormon and to spend much of your life focused on searching out your genealogy, determined to do temple work for the dead to redeem their souls in the next life, if you believe that they are “the bad guys.” Easier by far to come up with a story about why they—and you—are the persecuted, misunderstood good guys instead.

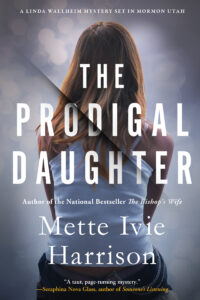

Maybe that’s why I’m a mystery writer, fascinated by murder among the very Mormons who like to tell stories about themselves in which only the “others,” the non-Mormons, could ever be the bad guys. My new novel, The Prodigal Daughter, is a story of a young woman who has run away from home in the dead of winter. Linda Wallheim is a Mormon bishop’s wife, and in each of the novels in this series she has come up against problems in Mormon doctrine, culture, and history as she investigates a local crime. In this story, Linda finds out once again how easy it is for Mormons to protect criminals in their own community, even to the point of blaming the victim. It can feel like accepting that Mormons are just as likely to be criminals as anyone else is the same as saying that the gospel isn’t true, that it doesn’t have the power to save, or that we aren’t safe within the community of good people around us, upon whom we often depend daily.

Do I have an axe to grind in writing a story about bad Mormons when I’ve stepped away from activity in the church? Am I trying to excuse my own choices in life? I suppose you could argue this. But I still think of myself as Mormon. I am protective of Mormonism to those who criticize it from the outside, while at the same time I speak clearly about the problems from the inside, to those I trust to hold the more difficult truth of the good and bad. The point of all my writing is less about showing the dark side of Mormonism and more about showing how human I think we are, with all the good and bad that entails.

***