It’s always interesting to learn about the hobbies of geniuses. The late Stephen Sondheim famously had two: the cinema (two of his musicals, A Little Night Music and Passion, were adapted from films), and crossword puzzles (he wrote the puzzles for New York magazine for a year). But Sondheim was also a big fan of crafting whodunits. He started planning murder mystery games for his friends in the ‘60s. Playwright Anthony Shaffer based Andrew Wyke, the ingenious, murderous plotter in his play Sleuth, on Sondheim. (At one point, the play was entitled Who’s Afraid of Stephen Sondheim?, but Sondheim suggested Shaffer change the title because not enough people would know who he was.)

Sondheim combined these three interests—movies, word games, and murder mysteries—in The Last of Sheila, a film he co-wrote with Anthony Perkins (of Psycho fame) in 1973. (Sondheim came up with the mystery plot, and both he and Perkins wrote the scenes.) But the film (directed by Herbert Ross) is a more than just a busman’s holiday for Sondheim. The elaborate nature of the mystery reflects Sondheim-the-composer’s gift for play with the traditions of form and genre. Its sophisticated detectives and suspects have much of the witty urbanity of Sondheim’s theatrical creations, as well as their moments of wistfulness, longing and self-doubt. Part dizzying mystery, part black comedy, part delicate camp indulgence, The Last of Sheila contains remnants and seeds of much of Sondheim’s groundbreaking theatrical work of the 1970s.

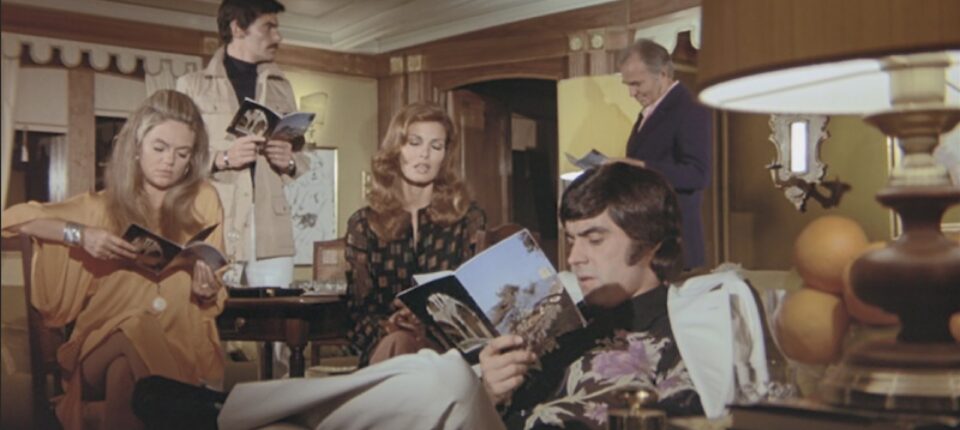

Part dizzying mystery, part black comedy, part delicate camp indulgence, The Last of Sheila contains remnants and seeds of much of Sondheim’s groundbreaking theatrical work of the 1970s.The film, directed by Herbert Ross, borrows a bit from Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, then adds a pile of extra clues and a dash or two of fizzy absurdity. Its plot is a riddle inside an enigma—or, more accurately, a whodunit inside a scavenger hunt. A year after his wife—the titular Sheila— is killed in a hit-and-run, the gleefully manipulative producer Clinton Green (James Coburn) asks a group of his friends and frenemies on a Mediterranean cruise. The group includes James Mason as a washed-up director, Raquel Welch as an up-and-coming starlet, Ian McShane as her wheedling husband, Dyan Cannon as a tell-it-like-is agent, and a struggling screenwriter and his wife (played by Richard Benjamin and Joan Hackett). Clinton, like Sondheim, loves devising complex games for his guests to play. For the cruise, he’s designed a kind of scavenger hunt that threatens to reveal his friends’ most dangerous secrets. Eventually, some begin to suspect that the real object of the game is to expose the person responsible for Sheila’s death. When Clinton himself is killed (dressed in drag, in the confession booth of an abandoned monastery) it seems like he’s not the only one playing games, and it will take a lot of amateur investigating (mostly by Mason’s dryly bitchy but keenly observant Philip) to separate the game from reality and, with the critical aid of a word puzzle, uncover a murderer.

All this makes Last of Sheila hard to characterize, and a little creaky in places. But the film is certainly a fantastically (if perhaps overelaborately) constructed whodunit, of a caliber you rarely see in on-screen murder mysteries. Most of them tend to underestimate the intelligence (not to mention the attention span or memory retention) of an audience. If you watch your average made-for-TV adaptation of an Agatha Christie mystery, for example, the plot usually gets streamlined. Some characters, subplots and red herrings are always cut out of the story: it’s too much ground to cover, and makes the eventual discovery of the solution seem far clearer in retrospect. Sheila, on the other hand, is wonderfully overstuffed and twisty. (I’m not going to spoil the mystery here, not just because I want you to enjoy the film, but also because I’m not sure I can explain it all myself without the length of a New Yorker article.) Clues and potential clues abound: ice picks, cigarette stubs, bourbon bottles and mysterious bits of wood. Christie (most famously in Murder on the Orient Express) asked her detective (and her readers) to distinguish between fake clues and the real one. At a murder scene, what has been left unintentionally, and what has been left deliberately as misdirection? This becomes key to cracking the multiple mysteries of The Last of Sheila, as the amateur sleuths have to sift out what clues were props for Clinton’s games, and what telling things the murderer may have left in their wake.

Sheila revels in its clever contrivances (much as Sondheim was sometimes accused of showing off with his lyrical wordplay in his shows). But it never forgets to let the audience in on the fun. The film’s first big set piece, where the friends run through the streets of a French port city for the first of Clinton’s “games,” is genuinely fun, and it sparks the audience’s own desire to play sleuth for the rest of the film. The movie also follows Christie’s rules, giving the spectator all the clues necessary to solve the crime on their own. It’s all there: in an emphatic close-up, a reaction shot that lasts just a little too long, a bit of throwaway dialogue that linger in the air. If you haven’t figured it out, it’s dazzling to think back on all the subtle oddities that could have pointed the way. Sondheim noted that Christie’s “solutions are full of surprises,” and the true solution in Sheila offers surprise after surprised, delivered in a climax and denouement of taut suspense and dark cynicism.

Another great pleasure of The Last of Sheila is the ways it heightens the camp elements that are inherent to the whodunit genre, but that are often repressed or understated. Characters in whodunits are often exaggerated “types”—their vivid expressions of personality both reveal and obscure their potential criminality. Sondheim said that, in a murder mystery, characters must be “vividly drawn” and “enormously colorful” and The Last of Sheila certainly delivered on that front. All these high-flying members of Hollywood’s elite have larger-than-life personalities. This is especially true of Coburn’s Clinton, who drags a sharp, maniacal relish out of each beat of his role of puppet-master. (At one point, while being lowered into a dinghy, he gives a speech about how he refuses to buy an island because none of them deserve a king like him.) Equally juicy is Cannon’s portrayal of Christine, whose lusty joie de vivre is barely deflated as bodies pile up. The other players, like Welch’s Alice (“Is it terrible, just terrible to wonder if there’s a good hairdresser in this town?” she asks after the murder) and Philip, with his acrid asides, amplify the whodunit’s dictum that some characters must have a comically Wildean view of murder as solely as an extremely irritating social inconvenience. You know that whodunit camp has been dialed up to eleven when there’s a scene where Ian McShane puts on an impromptu puppet show, and the murderer later uses those puppets as gloves to cover up their finger prints.

The Last of Sheila also shows some of the creative concerns of Sondheim’s theater in the years before and after the film.It’s easy to write it off as a one-off in Sondheim’s oeuvre, but The Last of Sheila also shows some of the creative concerns of Sondheim’s theater in the years before and after the film. Sheila’s well-sketched portrait of a witty, incestuous and codependent circle of friends is reminiscent of the characters in Sondheim’s previous musical Company. Clinton’s plan to expose Sheila’s killer has the marks of a revenger’s tragedy, a plot element that would also be incorporated into Sondheim’s most murder-y musical, Sweeney Todd. But the Sondheim show that Sheila anticipates the most is 1981’s Merrily We Roll Along, which is in large part a cautionary tale about the lures of Hollywood and the ways that success destroys friendships.

What’s striking about The Last of Sheila is the way that Hollywood amorality and the drive to succeed permeate the story. All the guests are only on the boat because Clinton is promising to profit off of tragedy by making a film about his late wife’s death. Each of them is eager, in one way or the other, to profit off Sheila’s death by participating in this movie. In The Last of Sheila’s conclusion, the murderer is not turned over to the police. Instead, the murderer’s friends blackmail them into financing the Sheila film, which will give them all work, while keeping the murderer on the sidelines of the project. The final image, of the murderer stuck at the fringes of the movie business (a kind of Sartrean hell) seems to be the Sondheim’s ultimate statement on Hollywood as profit-engine.

Though Last of Sheila can be read as a repudiation of Hollywood (and, in retrospect, a bonkers and totally improbable film), it has nevertheless made its mark on cinema. Rian Johnson’s Knives Out was partly influenced by The Last of Sheila. This can be most clearly seen in the doubled structure of the film’s mystery—what the dapper sleuth Benoit Blanc calls “the doughnut hole inside a doughnut’s hole.” The film’s willingness to “go full Last of Sheila” in its embrace of many twists, feints and fakeouts, all with a heavy dash of bitchery, gave the film a special verve completely lacking recent big-budget Christie adaptations. (In Knives Out, Johnson makes nods to Sondheim when Blanc briefly belts out Sondheim’s song “Losing My Mind.”) Publicity and paparazzi photos have already indicated that parts of Knives Out 2 are set on boats and in port cities, so it’s possible that we haven’t seen the last of The Last of Sheila, nor the last of Sondheim the master plotter. Hopefully, it will be another delightful avenue for his tremendous talent to live on.