Just seeing the words “Wes Anderson movie” will probably make you picture a very specific, highly-stylized aesthetic comprised of, among other things, symmetrical mise-en-scene, bright colors, old-fashioned intertitles, exaggerated acting patterns, quirky children who are more emotionally intelligent than their equally quirky adult counterparts, and probably Owen Wilson. Anderson’s famous cinematic style (created in concert with cinematographer Robert Yeoman, among other artists) has been the subject of art shows, parodies, and even an Instagram account-turned-book called Accidentally Wes Anderson, which assembles photographs of real-life locations that look like they could belong in one of Anderson’s films.

But just as Anderson’s particular style has facilitated his memorability and auteur status, it has also been criticized, itself, as being pretentious and unfeeling. Even the warm-hearted Moonrise Kingdom was criticized as having “almost scientific detachment” to its characters as well as featuring dialogue which is “is as stilted as ever.” This has led to the common perception that Anderson’s films are, to use a quote from the John Hughes film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, “very pretty and very cold.” But focusing on the restraints and limitations suggested by Anderson’s quirky visuals sidelines a discussion about how his stilted, baroque approach might actually, usefully represent emotion. Sincere emotions passionately course through all his films—but Anderson’s characters usually have to hold them in and keep them back, leaving these emotions to build up and then outwardly manifest in the most unexpected ways. Frequently via rebellion. Often, surprisingly, via crime.

From Anderson’s first film Bottle Rocket (which is about burglars), to his upcoming film The French Dispatch (whose multiple plots feature at least one set in a prison), Anderson has consistently played with depictions of crime and criminal activity throughout his entire body of work, alongside his characters’ wrestling with displays of their emotional depth. Even a film that does not feature crime as a main part of its narrative, such as The Darjeeling Limited, has a running gag involving repeated theft— signaling that co-protagonist Peter (Adrien Brody) is not so restrained as he appears. Anderson has arguably made as many films that deal with crime as Martin Scorsese, who famously picked him as “The Next Scorsese” in an editorial for the March 2000 edition of Esquire magazine. But Anderson is not necessarily interested in depicting crime for its own sake or out of an interest in the genre. Rather, Anderson weaves in tropes from crime stories as a structuring device, even as he stretches the parameters of the genre to reshape it in his own idiosyncratic, unexpectedly emotional image. Why, in worlds that are so vibrant and neat, do characters snap in the way they do? Why do they turn away from the idyllic to the criminal? Are their worlds so unsatisfying, or, really, are their worlds a reflection of their particularly unsatisfying lives?

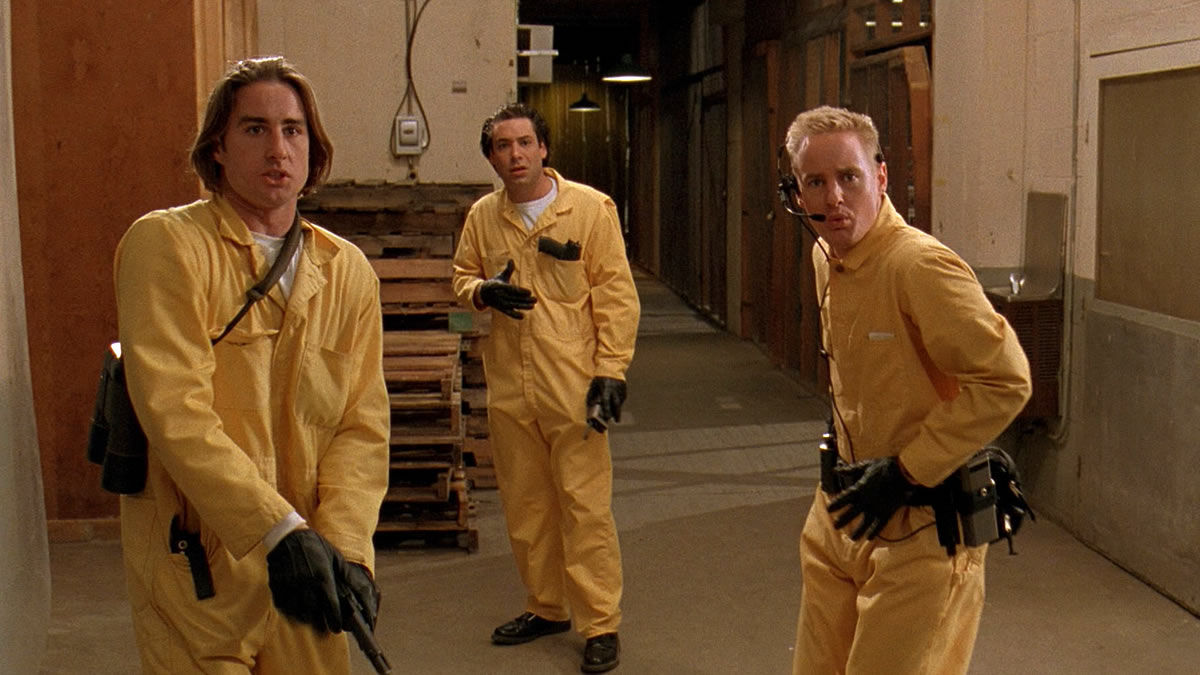

Anderson’s first film Bottle Rocket (which turns twenty-five this year) is his most straightforward take on the crime genre. It depicts the lives of existential Anthony Adams (Luke Wilson) and his enthusiastic best friend Dignan (Owen Wilson), who ropes Adams into committing robberies with a getaway driver named Bob Mapplethorpe (Robert Musgrave). On the surface it has many of the classic tropes of the late 20th century American crime film—young male criminals, life on the lam, and an impeccable interweaving of seminal rock songs (like “Over and Done With” by The Proclaimers and “2000 Man” by The Rolling Stones). Anderson even partakes in the popular 1990s trend in American cinema of casting great older actors who had not had a recent, prominent part in a mainstream film when he casts James Caan as the thief Mr. Henry. But Anderson continually puts his own twist on these tropes by making his young male criminals neurotic instead of cool, their lives of crime funny instead of ferocious—even if his needle drops were not yet as idiosyncratic as they later became.

In the opening sequence of Bottle Rocket, it appears that Adams is about to follow Dignan’s plan to escape from a psychiatric hospital. He is all set to climb down a makeshift rope to undertake a criminal escape to “freedom” when Dr. Nichols (Ned Dowd) enters to congratulate him on an early release. Adams sheepishly explains to Dr. Nichols that Dignan, not realizing that Adams’s stay was voluntary, enthusiastically came up with the scheme and Adams couldn’t bear to tell him no. “Look how excited he is,” Adams says as they watch Dignan look up at them through binoculars. Dr. Nichols lets Adams climb down the rope. As Dignan happily compliments him on “bribing the janitor” to help him escape, you can’t help but share Adams’s affection for his enthusiastic friend. Anderson goes on to play their ensuing robberies for laughs, subverting crime story tropes of competent criminals as Dignan’s incompetence brushes up against his great passion to become a highly successful burglar.

Bottle Rocket is particularly fascinating in the context of Anderson’s body of work because of how it lacks what the world has come to know as Anderson’s visual aesthetic. The realistic color palette is a far cry from Anderson’s later polychromatic pyrotechnics; there are no perfectly symmetrical horizontal tracking shots (Anderson would create his first in his next film Rushmore), and the characters’ clothes are nowhere near as distinctive as they would become in Anderson’s later films. But if this film lacks the most famous qualities of what would become Anderson’s visual aesthetic, it does have many of the hallmarks of Anderson’s emotional aesthetic. It features what some have described as his surface level distaste for overt emotionalism—Dignan advises Adams to “be sensitive to the fact that other people are not comfortable talking about emotional disturbances”—even as it establishes Anderson’s ability to create profound emotional moments.

One of these moments is when Dignan’s youthful ideals collide headfirst with grim reality when he gets arrested, a sequence which Scorsese described as “transcendent.” By the time Dignan marches back into prison after a nostalgic visit with Adams and Mapplethorpe, having finally found recognition as a criminal at the expense of losing his friends, Anderson has established that he can craft moving moments by exploring the tension between stiffness and emotion. Anderson switches to slow-motion as Dignan looks at his friends, the better to show off every micro expression of pain and longing for them that flits across his face. Dignan is clearly experiencing “an emotional disturbance,” but for once this enthusiastic young talker has no one to whom he can deny his feelings. Dignan stiffly walks back into prison before turning around to smile and raise his hands in a type of wave at Adams and Mapplethorpe. Caught between his unemotional life of crime and the genuine feelings he has for his friends, Dignan stays true to his principles of emotional coolness even as he lets Adams and Mapplethorpe know that he cares about them. Anderson would continue to explore the emotional lives of people who strive to not be seen as emotional as he began to expand his sense of worldbuilding.

The Royal Tenenbaums (which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year) is arguably Anderson’s most famous film. It is the first one Anderson made that features his full visual aesthetic in all its brightly colored, highly detailed glory. It is also the first of Anderson’s films to tweak the nature of reality. The Royal Tenenbaums takes place in a somewhat magical realist version of New York City that appears to be stuck in the 1970s and has such fictitious locations as “The Lindbergh Palace” and “The 375th street Y.” In addition, Anderson’s establishment of this story as a part of a fictional book called The Royal Tenenbaums—seen being checked out from a library in the film’s first shot—marks a major step forward in terms of Anderson presenting his work as something self-consciously literary. Anderson and editor Dylan Tichenor’s frequent cuts to shots of that book’s chapter titles and the presence of narration consisting of “text” from the book helps establish a certain emotionally distanced register.

Furthermore, Anderson makes many of his characters in this film authors of their own books. Whenever he introduces those characters, images of their books fill the screen. They cover such diverse subjects as fiction and finance. One cumulative effect of these literary references is to hold the audience at even more of an emotional distance than he did in Bottle Rocket. By riffing off established tropes in his depiction of the books within The Royal Tenenbaums, Anderson and his collaborators establish metafictional barriers to viewing the film’s characters as realistic people. At the same time, the range of the subjects and great beauty of the covers of the books written by Anderson’s characters perfectly capture the inventive and vibrant strengths of his then-new visual aesthetic. Many shots are so delightful that I frequently paused the film to look at them as if they were paintings. You can even glean more meanings from this film by pausing it. For example, if you would pause that initial shot of the book being checked out, you’d see that the biography of fictional author W.R. Wales lists The Royal Tenenbaums as Wales’s “first book of fiction.” It is fitting, then, that the film which “adapts” that book is the first one to depict Anderson’s full visual aesthetic.

The Royal Tenenbaums is many things—family saga, comedy, a collection of montages that would put most filmmakers to shame. Anderson and co-writer Owen Wilson (who also plays Cormac McCarthy-esque novelist Eli Cash) use crime tropes to provide an efficient structure for their sprawling thematic material, albeit with a subversive twist. The film is, in many ways, about a con artist trying to pull off one last trick. The con artist in question is Royal Tenenbaum (Gene Hackman), a colorful and cantankerous disbarred lawyer. He pretends to have cancer so he can repair his relationships with his wife and dysfunctional grown children.

But Anderson and Wilson subvert the trope of “the brilliant con artist” by depicting Royal as only being able to move back into the Tenenbaum family home thanks to the goodwill of his favorite son Ritchie (Luke Wilson). Anderson and Wilson go on to use another crime story trope—the unmasking of a deception—to reveal Royal as a fraud in front of his family. But the character who exposes him as a fraud is not his suspicious son Chas (Ben Stiller), as you might expect. Instead, it is Henry Smith (Danny Glover), the Tenenbaum family’s quiet accountant and new romantic partner of Tenenbaum matriarch Etheline (Anjelica Huston). Anderson and Wilson further subvert that trope by having it take place in the middle of their story instead of at the end, as it would in something more traditional such as Murder on the Orient Express. Their subversion of common crime story tropes is somewhat like pulling off a con because they use the audience’s faith to give them an experience they were not expecting.

Just as The Royal Tenenbaums features an explosion of Anderson’s now-ubiquitous visual style, so too does it feature the refinement of his emotional style. It is just as hard for these characters—particularly members of the Tenenbaum family—to display emotion as it is for them to see “what they can get away with” in terms of navigating their desires and conventional morals. One example is Ritchie’s relationship with his adopted sister Margot (Gwyneth Paltrow). They clearly love each other but have never been able to say so due to a host of reasons that include being adopted siblings. Ritchie continually tries to see how much of a real relationship he can have with Margot, despite his discomfort with her romantic past (shot as a montage in the style of a film like GoodFellas) and their tendency to communicate in a clipped, unemotional style.

The vibrantly colorful imagery surrounding them only throws the emotionally stunted nature of their potential and legally murky relationship into sharper relief. But Anderson shines in depicting their desire for each other in nonverbal ways, such as when Ritchie sees Margot for the first time in years. It plays in many ways as a reversed version of Dignan’s march into the prison at the end of Bottle Rocket. But instead of walking away from someone, Margot walks towards Ritchie in slow-motion. She does so, as if she has just gotten out of prison, as the Nico song “These Days” plays. The wistful guitar playing, romantic strings, and sadness of Nico’s voice convey the complexity of their feelings for each other in a more primal way than words could. But as effective as Anderson’s depiction of complicated, somewhat understated emotion is in The Royal Tenenbaums, it would be outshined by a later film’s more expansive use of that same formula.

The title card for The Grand Budapest Hotel announces that it will be Anderson’s most imaginative live action film. It informs us that its story takes place “on the farthest eastern boundary of the European continent” in “the former Republic of Zubrowka.” This puts it on an even grander scale than The Royal Tenenbaums. That earlier film merely created its own version of an existing city, while The Grand Budapest Hotel depicts life in a fictionalized country that exists in a fictionalized continent. Anderson matches that expansion in terms of geographic scale by structuring his film to have four frame narratives. The first features a young girl reading a book entitled The Grand Budapest Hotel. The book itself contains the three other frame narratives. They include the book’s aging Author (Tom Wilkinson) remembering a story he heard as a younger man (Jude Law) from the hotel’s ex-lobby boy turned owner Mr. Moustafa (F. Murray Abraham). These multiple layers create a high level of emotional distance that matches this film’s expansions in terms of originality and geography. But Anderson will go on to subvert that level of distance to create one of his most engaging and emotional films.

Anderson’s European epic deals with serious subjects, but he distracts viewers from its treatment of those issues by making his film a veritable feast of crime story tropes. He uses a murder as an inciting incident, quickly establishes a MacGuffin in the form of a painting which will be stolen several times, and has a climax involving a gunfight. This film has several mysteries for its characters to solve and thrilling chases, including a hilarious one involving skiing. There is even an entertaining yet bloody prison break. All of these entertaining crime story tropes act to keep the audience engaged despite the film’s treatment of serious issues related to how Fascism plagued 20th century Europe and the enduring pain of loss. But at the same time, Anderson is also unafraid to look at his characters’ moral gray areas. One of the most unexpected is when benevolent concierge M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes), in a moment of frustration, abandons his trademark manners to deliver a racist monologue to a younger version of Mr. Moustafa named Zero (Tony Revolori). But after learning that Zero only came to Europe as a refugee after the murder of his family, M. Gustave becomes overcome with emotion and apologizes to him. In doing so, he delivers the kind of sincere and meaningful sentiment affirming his support of Zero that this latest generation of Europeans should apply to those who seek shelter on their shores.

The Grand Budapest Hotel also features one of Anderson’s most compelling uses of surface-level emotional coldness. It makes up a vital part of a narrative thread concerning the relationship that Mr. Moustafa had with a baker named Agatha (Saoirse Ronan) when he was known as Zero. He first mentions her when discussing his relationships with people when he began working at the hotel, only to note that “we won’t discuss that” [their relationship]. This line may make it seem like Mr. Moustafa’s attitude towards Agatha shows him to be guilty of the coldness people often accuse Anderson’s characters of having. Even “The Author” seems to make this assumption about Mr. Moustafa, as when he notes that his “eyes went blank as two stones,” as if they only contain emotional coldness. But as the Author realizes, Mr. Moustafa’s eyes aren’t empty, but filled with tears. As Mr. Moustafa puts it, “I never speak of Agatha, because—even at the thought of her name—I’m unable to control my emotions.” Rather than a sign of emotional stuntedness, Mr. Moustafa uses coldness as a shield to protect himself from the pain of losing someone very important to him. His use of emotional frigidity to mask his grief is similar to how Anderson uses crime story tropes throughout the film: as a way to distract his audience from the pain in his story, even as it lingers like the taste of a delicious pastry made by the wonderful and dearly missed Agatha.

Mr. Moustafa’s attitude towards Agatha finds its most technically brilliant and poignant expression during the scene in which she marries his younger self, Zero. An initial medium close-up of Agatha and Zero shows them standing happily as M. Gustave performs the ceremony. But as Mr. Moutstafa discusses the later death of Agatha and their young child in a pandemic, the camera zooms back into a long shot, as if the memory of their past happiness is lost inside a greater landscape of pain and loneliness. Vladimir Nabokov once wrote of how love could overwhelm him with “the sense of something much vaster, much more enduring and powerful than the accumulation of matter or energy in any imaginable cosmos.” Zero clearly feels a similar love for Agatha. But the vast space that surrounds them at the end of their wedding scene does not hint at that love, but rather at the great loneliness he will feel when she is gone. The fact that Anderson can seem to condense decades of heartbreak into a simple camera movement is a reminder of his great skill at making films that, despite claims to the contrary, can be as emotional and heartbreaking as those of any filmmaker.

My favorite moments that dispel the popular perception of Anderson, and perhaps his work by extension, as cold and pretentious come from the 2015 Academy Awards. The Grand Budapest Hotel had received nine Academy Award nominations and won four of them. Anderson didn’t win a single Academy Award that night, but that did not seem to matter to him. As his collaborators—composer Alexandre Desplat, costume designer Milena Canonero, hair and makeup artists Frances Hannon and Mark Coulier, production designers Adam Stockhausen and Anna Pinnock—accepted their Academy Awards, he beamed lovingly. His facial expressions were so emotionally engaging that one of the people I was watching the Academy Awards with said that he wished there would be a “Wes Anderson cam” that would let you watch him all night. When his collaborators left the stage, Anderson applauded as heartily as anyone else. But, as that Oscar viewer that night pointed out to anyone who would listen, Anderson’s hands while he clapped were as perfectly symmetrical as one of his signature horizontal tracking shots. In that moment, Anderson seemed like one of his characters: brilliant, fond of expressing great emotion through stylized action, and proud of the gold his comrades were making off with thanks to his latest caper.