If a novelist uses real places in contemporary time for a setting, as many of us do, then we need to get the facts right about that location. This gives our readers an additional tool for suspending disbelief and immersing themselves in the story. I discover these sweet rich details of setting through two seductive channels: road trips and further research, either on the computer or, even better, in a library with a street address.

Because I anchor my stories in the Southwest where I live, I can slip into the car for on-site research. The journeys serve a dual purpose. They help me flesh out the mystery with sensory experiences I can’t get in my office using Google. And escaping from electronics into the real world re-charges my creative batteries. Both sorts of research seduce me. I spend longer savoring it than I should. There’s always a deadline gaining on me in the rearview mirror, approaching like a moving van bearing down on a dawdling Smartcar.

First Stop: Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness

In my newest novel, Cave of Bones, I wanted to take readers to a unique place that had its own mystery, a location where the series’ detectives hadn’t solved a crime before. First, I focused on the colorful landscape of the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, south of Farmington, N.M. The Navajo Nation manages the De-Na-Zin, giving my Navajo detectives reason to investigate. It seemed like a fine place to discover a murder victim.

So, in the name of research, my husband, dog and I made several trips, driving the three hours from our home in Santa Fe. We hiked, took hundreds of photos, had lunch, got sunburned and sandblasted, and eventually found our way back to our car. The area includes some sixty square miles of eroded hills, unworldly hoodoos, spires, pinnacles and graceful arches. I love the quiet isolation of this place. But, after the third trip, I concluded that there was too much light and color here for my purpose. A body would be hard to conceal. I filed away the Bisti for potential use in another story and considered a new setting. But the deadline moving van was gaining on me.

I removed my hiking boots and sat at the computer. I think best when I put my thoughts, as whimsical as they may be, into the words. I came up with a decent idea to open the book, but the setting alluded me. I took the dog for a walk. As I’m fixing dinner, inspiration arrives, and it calls for another road trip.

Next Stop: El Mapais

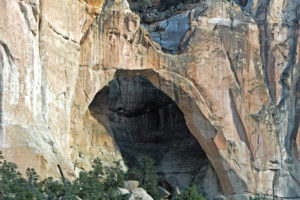

Near the Bisti, at least as we measure things here in the Southwest, I knew of another natural landscape, a dark landscape better suited to fictional chaos. I drive along the edge of this rugged, blackened country every time I travel west on Interstate 40 to Gallup and the Navajo Nation. Caves and lava tubes, treacherously sharp rock and boulders bigger than my car mark the place. Real people get lost in this country and some of them die before they are found. Even the name works: El Malpais, the bad land. It adjoins a section of the Ramah Navajo reservation, a crucial point for my tribal crime solvers. (They sometimes stray from their jurisdiction in the pursuit of justice, but only because I make them do it.)

Next Stop: Mount Taylor

Since the characters will need to spend time roaming in the lava to solve the case, I put my hiking boots back on. I’m in search of authenticity for descriptions beyond the obvious black and rocky, beyond cinder cones, craters and crevices. My husband isn’t up to the trip, and the dog keeps him company, but friends and I travel to where I hope the story can grown. I listen to the wind, watch the clouds dance, admire ravens as they glide, graceful black chevrons against the brilliant sky. I notice deer scat and raccoon tracks. I inhale chilled air kissed with moisture from melting snow. The stunning contrast between sandstone cliffs the color of cafe latte and the low black lava field a few yards away stirs more plot ideas. Mount Taylor, sacred to many Southwestern tribes, rises to the northeast. I could spend days here, seduced by the powerful magic of the place. It’s perfect, better than I could have invented. But I catch a glimpse of the deadline moving van rounding a corner behind me.

I listen to the wind, watch the clouds dance, admire ravens as they glide, graceful black chevrons against the brilliant sky. I learn that four different kinds of volcanoes and seventy-four volcanic vents created this foreboding place beginning some two hundred thousand years ago. The lava consists of two primary types, both named in the Hawaiian language because Hawaii is a center of volcanic study. they are pahoehoe, notable for its comparatively smooth surface, and aa (pronounced “ah-ah”), solidified chunks of angular rock. In the novel, I invent a character with a passion for geology to explain this to my character as they struggle over the rugged terrain looking for a key to the mystery.

Aldous Huxley used this place in the second portion of Brave New World and Cormac McCarthy set a scene in Blood Meridian here. That master of the American Western, Louis L’Amour, brings a character to a hidden camp site in this lava field. I was tempted to expand my research by reading what they had written, but, in my imaginary rearview mirror, the deadline van is blinking its lights.

I am surprised to discover that the lava field could have been blown to smithereens in the 1940s. This relatively empty place was one of eight sites considered by the Manhattan Project to detonate the first atomic bomb. (Ultimately, the government picked another beautiful spot in New Mexico, the White Sands Proving Ground.) Can I get this in the book? I reel in my enthusiasm and remember that my readers want the story to glow and erupt. These details don’t make the final draft.

From previous research, I knew that traditional Navajo stories view the lava as the solidified blood of a monster killed by the Hero Twins in their quest to make the world safe for us, the Five-Fingered People. As I looked out over miles of black and red rock, I wondered what the Pueblo Indian people who live nearby make of this place. What do their stories say about the lava field? Ancestors of the Acoma, Laguna and Zuni Pueblo people left ancient artifacts in this stony landscape; modern prayer sticks are here, too. I find the question seductive. It’s worth another research trip.

Next Stop: the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture Laboratory of Anthropology Library

I make a phone call and head off to the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture Laboratory of Anthropology Library. It’s a special collections archive dedicated to the study of America’s Native cultures, anthropology and archaeology with the concentration on the greater Southwest. Luckily for me, a librarian there seems as fascinated as I am by the question of how the ancient ones explained the lava. She finds out-of-print volumes filled with stories. Even their smell says mystery and wonder. Hours go by. I inhale dramatic, irresistible information, none of it quite what I need. I explain my question more clearly and the librarian ferrets out more old books. Meanwhile, the deadline moving van crowds my back bumper and honks.

If the road isn’t headed where my book needs to go, I can get off at the next exit, a little wiser for the detour. Just when I am on the verge of regretfully concluding that I’ll have to leave this research cul-de-sac, I find what I need. A story from one of the pueblos speaks of a supernatural being, a gambler who attempts to destroy the world with pitch and fire but is thwarted by a rain god who cools the pitch and turns it to rock. Another tells of terrible monsters who come up from the underworld and are destroyed by the gods with lightning. They melt into smoldering black stone.

I pull free from the seductive embrace of research and the freedom of the open road and return to the challenge of writing the book. I incorporate a fraction of what I’ve learned in a way I hope the readers will enjoy.

Curiosity about the world and its people, about why things are as they are, is one of the engines that drives me, and most of us writers, to learn more about a subject that we can squeeze into a novel. I know I’m not the first to be seduced by research. Sometimes the research trips will change the course of the book for the better; sometimes they provide happy, off-road diversions and, if I’m lucky information I can incorporated in subsequent books or even essays like this. I don’t know until I put the key in the ignition my foot on the gas pedal. If the road isn’t headed where my book needs to go, I can get off at the next exit, a little wiser for the detour.