On the wall behind my office desk hangs a large, finely detailed street map of my hometown, Minneapolis, Minnesota, circa 1950s. Almost everything I’ve written over a long career––fiction and nonfiction both––has been situated on its rectangular grid, circumscribed by the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers and dotted by its famous Chain of Lakes.

Minneapolis has been a wonderful place to grow up, raise a family, and pursue a career, only recently more famous––infamous, sadly––for its police brutality and destructive riots than the blue water and sailboats in the tourism commercials. During the middle ’50s, when I was a kid, Minneapolis (like its so-called sister city, St. Paul, across the Mississippi) was almost all white, predominantly Scandinavian, German, and Irish, and heavily Protestant and Catholic. Blacks and Jews were redlined out of most residential neighborhoods and restricted from many of the most desirable employment opportunities, institutions, and social clubs. But what did I know, a Swedish Lutheran kid minding my business in an anonymous pocket of the South Side?

Well, I knew that terrible things could happen here, sometimes not far from my vanilla neighborhood, sometimes in neighborhoods our streetcar or bus would rattle through when my mother and I traveled downtown for a doctor’s appointment or to look at the Christmas displays in Dayton’s windows. In those days, Minneapolis, like most large cities, had both a morning and an evening paper, and beginning as far back as I can remember, I was an avid reader of both. I read about a Northside bootlegger and “white slaver” (whatever that was) named Kid Cann, the kidnapping and murder of a little Southside girl, and the strangled body of a small-town woman discovered in a fancy neighborhood and the arrest and murder trial of her dentist. I learned that my pretty, peaceful City of Lakes could be a scary place.

Many years later, I would write about several local horrors, mindful of the juxtaposition of placid, ho-hum normalcy and sudden, brutal, often inexplicable violence. The dark corners of my sunny city fascinated me as a writer, the shocking appearance of darkness in its sunny corners even more. All three of the true-crime books I’ve written in the past fifteen years and my four Midwestern noir novels have been set in the Twin Cities. Though I’m acquainted with interesting locations around the country and abroad, I’ve never had difficulty siting my grim tales right here at home.

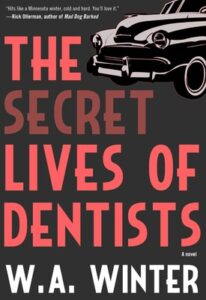

My new novel, with its improbable title, The Secret Lives of Dentists, was inspired by the 1955 murder of Mary Moonen and the case against her Jewish dentist, Dr. A. Arnold Axilrod. The case was a regional sensation that played out in several familiar locations around town, from the seedy stretch of Nicollet Avenue (since obliterated by Interstate 94) where Axilrod practiced “sedation dentistry” with mostly female patients to the iconic Hennepin County courthouse where Axilrod’s lurid, six-week-long trial took place.

I say the novel was inspired by, not based on, the Axilrod case because I wanted to tell a richer story than I could with nonfiction. My victim, whom I call Teresa Hickman, and her alleged murderer, my Dr. H. David Rose, shared characteristics with the real people, but with names, backgrounds, families, personalities, and proclivities that emerged from my imagination. My large cast of supporting characters––cops, lawyers, journalists, creeps––were all mine, albeit in some instances inspired by people I knew or know. Most of the many sites, including the magnificent courtroom and spartan homicide-unit offices, are actual locations, though I have reimagined them. Other sites, such as the greasy spoon where Terry Hickman briefly works and a couple of her pursuers hang out and Dr. Rose’s claustrophobic offices down the hall from a chiropractor and a dance studio above a raucous nightclub reflect ordinary urban settings that I have molded to my narrative’s needs.

Some settings, such as the ivy-faced Tudor Revival home where Rose lives with his wife and two daughters and the dingy basement apartment where a sex-obsessed young reporter beds his latest conquest, can be found in the neighborhood where my wife and I raised our kids and an inexpensive rental unit where I lived a hundred years ago (or so it seems). Nearly every morning, when I walk my dog, I pass the weedy patch along the old trolley right-of-way where Terry’s body was discovered. Sixty-plus years have passed so I had to picture the surrounding neighborhood through imaginative eyes, with fewer single-family homes and more two- and three-story apartment buildings, including the one where that horny tyro and an earlier inamorata commit adultery. The site also lies only five blocks from the dentist’s imagined home.

Not for the first time in my fiction I’ve very carefully placed my tale in the distant past, when I, now only slightly younger than our oldest President, was a kid and young man. I love recreating the “details” that I conjure from the past, making changes as needed. Dr. Axilrod, for instance, drove a black Kaiser Frazer sedan, but I put Dr. Rose behind the wheel of a black Packard Clipper because, in my mind, the Packard offers a more sinister image. The Minneapolis United Press bureau––noisy, smoke-filled, and malodorous––is long gone from the Portland Avenue perch it occupied when I worked there, but it’s still very much alive in my book.

“Write what you know,” we’re told. I know Minneapolis, including the Minneapolis that’s now only a memory. I know the 1950s, too, and what I don’t remember about either the city or the times I can shake loose from old newspapers, historical archives, and vintage maps like the one on my wall.

Historical fiction, when not confined by the total accuracy required of a journalist or historian, has a better chance to recreate the subjective reality of the period described, to evoke in the reader’s mind the sights and sounds and smells that bring the tale to life.

***