My writing career began with seventeen standalone crime fiction novels, including Oblivion, End of Story, A Perfect Crime, Lights Out, Hard Rain, and Nerve Damage. You’ve probably guessed already these are not cozies, in fact, are shifted to the dark end of the spectrum. Correct! Bad things happen to the good and the bad, and when justice is served the meal is on the haphazard side, messy and sometimes indiscriminate. But the plots all makes sense, I hope, since a story with a plot that doesn’t make sense is ruined for me, no matter how admirable its other qualities.

Back to darkness. In End of Story, where aspiring writer Ivy lands a gig teaching writing in a men’s prison, we even get to read a snatch or two of inmate crime writing—not, unfortunately for Ivy, crime fiction. In Lights Out, the protagonist ends up breaking back into prison. In A Perfect Crime, a character realizes, perhaps a little late, that the truly perfect crime has the punishment baked in. Of Bullet Point, the young adult novel that came after the Edgar-winning Reality Check and that I prefer, I will now disgrace myself by quoting a reviewer: “As tough and gritty a YA thriller as I’ve ever read.” There! Have I made my point? Darkness and me, conjoined.

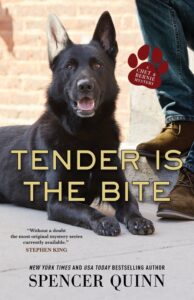

And then along came the Chet and Bernie private eye novels, written under my pen name, Spencer Quinn. They’re of the buddy type, where one partner, like Dr. Watson, tells the story. In this case Bernie is the detective and Chet is the narrator. Yes, he’s a dog, but not a talking dog! He’s as canine as I can make him. What dogs don’t know, Chet doesn’t know, often in spades. But what dogs do know—and feel—Chet knows and feels to the max. Here, from Tender Is The Bite, is a taste of Chet’s narration, “taste” maybe an unfortunate choice in this instance:

Bernie, on his knees, moved over to me, put his hand on my back. “You okay?”

Perfectly fine. That was the cool thing about puking. You feel bad just before, and when you’re doing it, but the moment it’s over you bounce back to feeling your tip top self. At least that’s how it works for me.

As a companion to Bernie, Chet couldn’t be more reliable; as a narrator, rather less so. When his particular brand of unreliability gets loose within the strict plot confines of traditional detective fiction, some new things start happening, a challenging and also exciting development for the person who’s supposed to be at the controls. But that wasn’t even his main influence on me, which was that Chet led this writer, as though on a leash, away from darkness.

It’s not that the Chet and Bernie novels are cozies. Dark things happen. There’s violence, although I’ve always been more interested in the run-up to violence and the aftermath than in the description of its eventual expression. There’s also thematic material—I’m not a fan of themeless literature, although I also don’t want themes in my face—just as in my earlier work. For example, Tender Is The Bite is about politics, kind of, defined by Chet on page nine, sort of. And some of the dark things happen to the good, both humans and non-humans, Chet included. He’s a deeply emotional character in many ways, but I began to notice that he always bounces back to his reset position very quickly, and that reset position is all about joie-de-vivre. That’s not me at all, but crazily enough I began, in what I no doubt mischaracterize as late middle-age, to start tilting in that direction. It’s even possible—although not for me to say—that I might be more pleasant to be around.

But how can that be? Isn’t Chet a figment of my imagination, and in that sense unreal? How can he influence the real me? That’s where I’ve left things for the past few years or so, but recently when I was asked if I was ever going to write the dark kind of Peter Abrahams novel again—a fairly common question in my life—I began to rethink the issue of Chet’s influence. (The Chet and Bernie novels are the only ones I’ve written in the first person, by the way. I wonder if … hmm.)

My usual answer to the return-to-darkness question is that I actually have written an Abrahams-type novel fairly recently, even though it came out under the Spencer Quinn pen name (The Right Side, 2017), and I add that I may write more in future (and in fact there’s a non-C&B novel coming in two years or so). But digging deeper, the way a psychiatrist might— at least in my imagination, since I don’t know any—what if Chet is an expression of some change in me, and not the cause? Aren’t people supposed to become more pessimistic with age, like grumpy old men? Don’t most of us end up disillusioned? Why do I seem to be headed in the other direction, maybe even toward illusion, but happily so?

And then it hit me: I started out disillusioned! Lights Out! Oblivion! End of Story! I mean, come on! Been there! Done that! There was nowhere else to go. As Chet puts it in Tender Is The Bite, a propos of a plot point that drives the story forward, but more important in other ways: “Maybe it helps to know yourself in this life. I, Chet, cared about steak tips.”

Therefore I will now set up shop as an advisor to the aging (which excludes no one, as you will learn if you don’t already know). To begin: Go down to the shelter and select a likely looking customer. Give him or her a name. “Sparky” is tried and true. If you already have a Sparky at home, take your Sparky for a walk right now. A T-R-E-A-T comes next.

***