Our living rooms were once called death rooms. Back in 1918, as influenza swept through households, killing millions, the pandemic necessitated a space within our own homes to host the dead. The front room—parlors, derived from the French ‘parle,’ or ‘to speak’—was the designated chamber under our very roofs where living relatives could sit with their loved ones one last time. We could reminisce with the dead and bid farewell as a family before the body was bound for its funeral. Once immunities improved and the number of flu-borne deaths decreased, these mourning rooms were no longer deemed necessary, essentially phased out of their domestic lamentation.

Leave it to the Ladies Home Journal to suggest that our death rooms should become rooms for the living, suggesting a name change.

Without a designated mourning room, death crawled under the upholstery and under the wallpaper… and into our libraries. Where could we speak to our dead now? In our books.

I need to make a confession: I’ve turned my friend into a ghost story.

I’ll keep him anonymous—but growing up, in and around our teens and early-twenties, my friend was the Kerouac to my Burroughs. We grew up cosplaying the Beats, wanting to believe we were the second coming of our favorite poets. His lust for life was a beautiful, intoxicating thing that the rest of our circle of friends swooned through and tried to keep up. Being in his orbit was thrilling and invigorating and utterly exhausting all at once.

Drugs eventually entered the fold. Rather than help, I drew a hard line that neither of us crossed. It ended up severing our friendship forever. I thought it was tough love, but it wasn’t. I was simply being selfish. I wanted to believe he could clean himself up but he overdosed soon thereafter. The world lost him—I lost him. I wasn’t there when he needed me the most.

I remember getting the call. I remember where I was—the exact location (a college dorm room during the summer where I was attending a writers workshop), the temperature (there was no A/C and the humidity felt like an organic presence all on its own), the very feel of the phone in my hand (an early gen Nokia, a Matchbox car without wheels)—when a mutual friend shared the news.

I don’t remember much after hanging up.

Life doesn’t give us any do-overs, but in fiction, we can become Frankenstein’s to those pivotal moments in our past, stitching them back together however we please. Circumstances might never offer me a chance to say goodbye, but what was stopping me from replicating our friendship on the page, where I could play God? Here was a chance to go back in time and try again, say the things I never got to say to my friend when he needed me the most.

I started writing about him.

But you can’t bring the dead back without there being consequences. Much like with Mary Shelly’s monster, the folly in my actions, my hubris, is that it takes place in a (southern) gothic horror novel.

Everybody talks about the roller coaster of horror. Genre as thrill ride—Hop on this horror movie and feel your pulse pick up… Slip inside the pages of this book and let the flood of adrenaline rush right over… Imbibing horror is an exercise in controlled annihilation, a stimulating simulation that safely satisfies our curiosity over death. Feel the feels without any of the real risk. Participants inch up as close to their own mortality as they possibly can—the slice of the serial killer’s blade as it slashes through the air, the vampire’s fangs sinking into the flesh of our necks, the fetid eclipse of a dozen zombies tearing us limb from limb—then walk away, unscathed and exhilarated, having tapped at the trauma without actually enduring it.

But what if we go to horror for our grief? What if we don’t want to simply experience the simulacra of death, but to commune with those on the other side of it? Horror as a genre—its books and films—are our death rooms, our mourning spaces, now. Where else can we claim an environment that enables our sorrow the chance to engage with those who we have lost?

Where else can we keep our ghosts?

Nobody knows your grief. Not your friends or family.

Horror does.

Death, when it comes home, disrupts our status quo. Whatever façade of control we may have had when it comes to our day-to-day lives is stripped away the moment we lose someone we loved. We are left in the abyss of our sorrow, flailing. We are told that time will heal all wounds. That, one day, we’ll move on.

Horror doesn’t want you to heal. It wants you to scream. It offers catharsis by showing you the grisly bits that others in our daily existence tend to shy away from. Everybody else around you wants you to move on with your life. Not horror. Horror wants you to be in the here and now, to linger in the present tense while everything around you spins out of control.

There is no control. There never was.

Now you know.

Consider the mother in “The Monkey’s Paw.” To me, Mrs. White is the distillation of grief in horror. The O.G.—original griever. The lengths that she will go simply for one more look, just one more, at who she lost. Her husband is already in the process of moving on with his life. He knows their son is never coming back… Or can he? All it takes is a wish, one simple wish of the monkey’s paw and their pride and joy, their son would return home. “Bring him back,” cried the old woman and pulled him towards the door. “Do you think I fear the child I have nursed?”

Who amongst us wouldn’t wish for the very same thing? Hand that paw right on over and let’s see what we might be tempted to try in the name of love for those we’ve lost…

What are the lengths that you would go for a loved one? What depths would you plummet? We are told about Orpheus’s love being so strong, that he traveled all the way to the underworld to get his beloved back. Louis Creed disinterred his son’s body, reburying him in the tainted soil of Pet Semetary, to bring Gage back. Look at the recent novels that have released their grief onto the page—The Fisherman by John Langan, The Devil Takes You Home by Gabino Iglesias, This Line Between Us by Gus Moreno, Come With Me by Ronald Malfi, just to name a scant number, not to mention films like Ari Aster’s one-two sucker-punch of Hereditary and Midsommar, The Descent (its UK cut, not the tepid American release, mind you), The Babadook and Lake Mungo, and see how they make more sense out of the senseless simply by showing us how messy, how completely raw, our grief can be, should be, encapsulating the chaos of loss.

Readers gravitate to grief-horror because it doesn’t pander. It doesn’t ask us to heal. It won’t try to console us or offer empty platitudes. It shows us characters in a state of utter flux, where the world they knew—or thought they knew—has bottomed out, leaving them reeling against things they can’t control, that they never truly had control over. The façade is gone.

Horror as a genre is the great disruptor. It turns our protagonists’ lives upside down. Same with the author. As my new novel took shape and I necromanced my friend onto the page, drafting him back to life like some Stephen King protagonist gone off the deep end, there was this constant voice whispering at the back of my mind—I don’t know if I should be doing this—but much like Louis Creed in Pet Semetary, when have the voices in our head ever stopped us from embarking upon the sojourns our stony hearts set us upon?

I wanted to build a monument for my friend. I wanted to honor him. I wanted to explore my own shortcomings, my failure as a friend. This book would become its own private memorial, a personal space where I could revisit my friend and say the things I never got to say when he was still alive.

I made a mourning room. Not just a death room—I built an entire house for him to haunt, where I could sit in that front parlor with him one final time. It was fiction, a fabrication, but it was all I had, all any writer has, a chance to rewrite history. To try again. Do it right this time. Or the next. However many times it takes. This was my chance to say I was sorry.

That first draft—raw, shapeless, a nebulous tangle of words—worried my editors. I’ll never forget their summation of what I submitted to them: Relentlessly interior. Grim. Plotless.

Turns out I wrote a hollow tomb for my friend. It wasn’t him, it never could be. It wasn’t his voice, now full of gravel of dirt. It didn’t look like him, not entirely, his features a stitched patchwork of what he truly looked like before. He didn’t act the same, didn’t move the same. Here was this shambling approximation of my friend, him and not him all at once.

In the process of trying to exorcise my own grief, something happened that I hadn’t intended… The character took on a life of his own. I didn’t recognize my friend anymore. It wasn’t him on the page. This character was some pale imitation of the person I lost, much like the embalmed body resting in an open casket—the off-color powdered face, the stiff pose, the uncanniness of their corpse. What I was looking at was nothing but the hollow shell. The body. Not the human being. Not my friend.

My friend is gone.

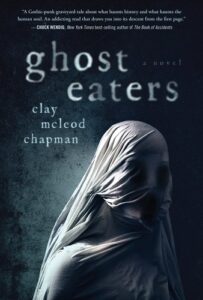

My novel Ghost Eaters is about a haunted drug. Pop a pill, see the dead. Not just any ghost, but those you loved and lost. I lost my friend and I wrote a book in order to rectify my mistakes. The book is an open casket and I’m an awful embalmer. When I lean over and peer into its pages, the character I see is not the friend I lost, but some hollow approximation of him.

I monkeypawed myself. Just like Mrs. White, I made that wish—bring him back—only I wasn’t fortunate enough to have someone close to me make that third wish without my knowledge, sparing me this fate of seeing what’s become of our loved ones. I have been waiting in this mourning room of my own making, built just for the two of us, and now I must bear witness to the gruesome fruit of my own grievous need to resuscitate my friend, realizing far too late that this character I revived in the name of love is just a pale approximation of who he truly was.

What I brought back from the dead isn’t my friend at all.

Now I have to live with that.

***