“Murder is the unique crime, the only one for which we can never make reparation to the victim. Murder destroys privacy, both of the living and the dead. It forces us to confront what we are and what we are capable of being.”

P. D. James loved the writers of Golden Age mystery fiction—Christie, Sayers, Marsh, Allingham, Tey—the manor houses, the closed circle of suspects, the patient investigator unearthing long-buried secrets and motivations, the restoration of order to a disordered society. She also knew they had flaws—realism and psychological subtlety sometimes took second place to the mechanics of the plot; police procedures and forensic science were often fanciful; and, especially, those notions of order and disorder simply didn’t fit the ambiguities of the post-World War II world:

“Crime writers today know only too well that corruption can lie at the very heart of law, that not all policemen are invariably honest, that murder is a contaminating crime which changes all those who come into touch with it, in fiction as in real life, and that although there may be—indeed must be—a solution at the end of the detective novel and a kind of justice, it can only be the fallible justice of men” (Time to Be in Earnest, 1999).

It was just that fallibility that most fascinated her. “We none of us know another human being so well that we can be absolutely sure about him,” she wrote in Innocent Blood (1980), and she peopled the novels she wrote from 1962 to 2011 with an astonishing array of characters, each one—even the smallest—etched with care as their lives unraveled under the revealing trauma of a murder inquiry. Blending the traditional detective story with the psychological thriller, she explored themes of obsession, revenge, neglect, ambition, morality, greed, deceit, identity, the existence of evil, and the implacable force of the past, all in prose that was at once elegant and graceful, sometimes tinged with dry humor, always filled with remarkable power.

Labeled “the greatest contemporary writer of classic crime,” “the best practitioner of the mystery novel writing today,” and “a craftsman with a poet’s vision,” she was often said by critics to have “transcended” the genre. I have never liked that phrase myself. I’ve always felt that crime fiction has done quite nicely all by itself, thank you very much, with no need to be “transcended.” What is true, though, is that James took the detective novel and helped to refine it, deepen it, amplify it. She liked to compare the form of the traditional detective novel with that of the sonnet—no one claimed that the fourteen lines and strict rhyming scheme of the latter constrained it from becoming great poetry; likewise there was nothing in the contours of the detective novel that kept it from becoming great literature.

For her, the key to her books was always the setting. The single body on the drawing-room floor was more horrifying than a dozen bullet-riddled bodies on noir’s mean streets, because it was shockingly out of place. The contrast between respectability and planned brutality intensified the magnitude of such an appalling act. Setting also provided the stage for everything to come—it created the mood and atmosphere; it told you who these people were as much as their actions did. That is why her policemen and detectives always closely examine the murder scene—not just for clues to the murderer, but for clues to the victim, to how he or she ended up a corpse: “The detritus of a murdered life told its own story. The evidence of the victim’s pathetic leavings, letters, bills, could be misinterpreted, but artifacts didn’t lie, they didn’t change their story, they didn’t fabricate alibis” (Original Sin, 1994).

To read a James novel is to acquire an intimate knowledge of flats, kitchens, offices, gardens, villages, castles, clinics, schools, hospitals, houses great and small—and the lives that are lived there. She was particularly fond of isolated places and closed communities: a nursing home on the Dorset coast (The Black Tower, 1975), an island estate off Cornwall (The Lighthouse, 2005), a power station on the Norfolk shore (Devices and Desires, 1989), a forensic science lab in East Anglia (Death of an Expert Witness, 1977), a theological college by a crumbling cliff (Death in Holy Orders, 2001).

And even if the setting wasn’t isolated, it was the closed community, the hothouse atmosphere of people too close to one another, that fascinated her: the museum staff in The Murder Room (2003), the publishing house in Original Sin (1994), the nursing school in Shroud for a Nightingale (1971), the law chambers of the Middle Temple in A Certain Justice (1997).

Wherever it was, James would set the scene before us in prose that was precise, evocative, layered, immediately engaging all the senses:

“It loomed up out of the darkness, a stark shape against a grey sky pierced with a few high stars. And then the moon moved from behind a cloud and the house was revealed; beauty, symmetry and mystery bathed in white light” (“The Mistletoe Murder,” The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories, 2016)

“The window was slightly open at the bottom. He pushed it open, wincing at the rasp of the wood, and put out his head. The rich, loamy smell of the fen autumn night washed over his face, strong, yet fresh. The rain had stopped and the sky was a tumult of gray clouds through which the moon, now almost full, reeled like a pale, demented ghost. His mind stretched out over the deserted fields and the desolate dikes to the wide, moon-bleached sands of the Wash and the creeping fringes of the North Sea. He could fancy that he smelled its medicinal tang in the rain-washed air. Somewhere out there in the darkness, surrounded by all the paraphernalia of violent death, was a body” (Death of an Expert Witness).

“The corpse without hands lay in the bottom of a small sailing dinghy drifting just within sight of the Suffolk coast. It was the body of a middle-aged man, a dapper little cadaver, its shroud a dark pin-striped suit which fitted the narrow body as elegantly in death as it had in life. The hand-made shoes still gleamed except for some scruffing of the toe caps, the silk tie was knotted under the prominent Adam’s apple. He had dressed with careful orthodoxy for the town, this hapless voyager; not for this lonely sea; nor for his death.

“It was early afternoon in mid-October and the glazed eyes were turned upwards to a sky of surprising blue across which the light south-west wind was dragging a few torn rags of cloud. The wooden shell, without mast or row locks, bounced gently on the surge of the North Sea so that the head shifted and rolled as if in restless sleep. It had been an unremarkable face even in life and death had given it nothing but a pitiful vacuity. The fair hair grew sparsely from a high bumpy forehead, the nose was so narrow that the white ridge of bone looks as if it were about to pierce the flesh; the mouth, small and thin-lipped, had dropped open to reveal two prominent front teeth which gave the whole face the supercilious look of a dead hare” (Unnatural Causes, 1967).

James devoted the same attention to her characters. It made no difference how crucial or incidental they were, each one told a story.

James devoted the same attention to her characters. It made no difference how crucial or incidental they were, each one told a story. Sometimes the character note was rapier-quick—“The police sergeant was looking at him with the resigned and slightly pitying look of a man who has seen too many men make fools of themselves to be surprised, but still rather wishes that they wouldn’t do it” (Cover Her Face, 1962); “Mrs. Crealey, sherry bottle in one hand and a scrap of jotting pad in the other, munched at her cigarette holder until she had maneuvered it to the corner of her mouth, where, as usual, it hung in defiance of gravity, and squinted at her almost indecipherable handwriting through immense horn-rimmed spectacles” (Original Sin).

However, James was at her best when she allowed herself to stretch out:

“She was a thin, brown-skinned woman, brittle and nobbly as a dead branch who looked as if the sap had long since dried in her bones. She gave the appearance of having gradually shrunk in her clothes without having noticed it. Her working overall of thick fawn cotton hung in long creases from her narrow shoulders to mid-calf and was bunched around her waist by a schoolboy’s belt of red and blue stripes clasped with a snake buckle. Her stockings were a concertina around her ankles, and either she preferred to wear shoes at least two sizes too large, or her feet were curiously disproportionate to the rest of her body. She had appeared as soon as summoned, had plonked herself down opposite Dalgliesh, her immense feet planted firmly astride, and had eyed him with anticipatory malevolence as if about to interview a particularly recalcitrant housemaid” (Shroud for a Nightingale).

“For Venetia the change from the long-established provincial single-sex high school, with its slightly snobbish conventions and local traditions, was less traumatic than she had expected. It was as easy to be a loner at the new school as it had been at the old. She coped with the few bullies by a tongue which could lash them into silence; there was, after all, more than one way of making oneself feared. She worked hard in school, harder still at home. She knew precisely where she wanted to go. The three top-grade A levels gained her an Oxford place. The first-class degree was followed by an equally brilliant academic success in her Bar examinations. By the time she went up to Oxford she thought she knew all she needed to know about men. The strong could be devils; the weak were moral cowards. There might be men she would sexually desire, even admire, come to like and even want to marry. But never again would she put herself at the mercy of a man” (A Certain Justice).

“As Graham Greene once wrote,” James said, “I have a splinter of ice in my heart. If I had a friend in distress, I would have no hesitation in putting my arms around her to comfort her, but part of me would be observing the scene.”

James’ most important character was, of course, Adam Dalgliesh, one of the most iconic figures in crime fiction. The only child of an elderly couple, the son of a vicar, he lost a wife and baby son early on, and since then has led a very private life. He is also a respected poet, a fact that mystifies many onlookers who can’t quite square one man being both a poet and a policeman. Dalgliesh also worries about it himself sometimes: “People tell me things. It had begun when he was a young detective-sergeant and then it had surprised and intrigued him, feeding his poetry, bringing the half-shameful realization that for a detective it would be a useful gift. The pity was there. He had known from childhood the heartbreak of life and that, too, had fed the poetry. He thought, I have taken peoples’ confidences and used them to fasten gyves round their wrists” (The Murder Room).

James always said that she gave Dalgliesh the qualities she most admired in either men or women—“compassion without sentimentality, generosity, courage, intelligence, and independence” (A Certain Justice)—but some of those qualities can cut both ways. His detachment is both his strength and his weakness: “How long could you stay detached, he wondered, before you lost your own soul” (A Mind to Murder, 1963). His independence and lack of sentimentality make him prone to personal antipathies and occasional sudden anger, and his “cold sarcasm could be more devastating than another officer’s bawled obscenities” (Devices and Desires).

However, he is a listener, be they witnesses, suspects, or his own team members. “This quiet, gentle, deep-voiced man,” thinks one interviewee, “hadn’t bothered to commiserate with her on the shock of finding the body. He hadn’t smiled at her. He hadn’t been paternal or understanding. He gave the impression that he was interested only in finding out the truth as quickly as possible and that he expected everyone else to feel the same. She thought that it would be difficult to tell him a lie” (A Mind to Murder).

James always said that she gave Dalgliesh the qualities she most admired in either men or women—“compassion without sentimentality, generosity, courage, intelligence, and independence.”

These qualities, though, can also strike terror in his subordinates. When he invites them to talk with him about what they had seen and heard, it meant that he “now expected to hear a brief, succinct, accurate, elegantly-phrased but comprehensive account of the crime which would give all the salient facts so far known to someone who came to it freshly. This ability to know what you want to say and to say it in the minimum of appropriate words is as uncommon in policemen as in other members of the community. Dalgliesh’s subordinates were apt to complain that they hadn’t realized a degree in English was the new qualification for joining the C.I.D.” (Shroud for a Nightingale).

What he hears, though, is key, and out if it will often come an intuitive sense that something important has been said. It isn’t a “hunch,” it’s a certainty, and his team has to respect it: “Inconvenient, perverse and far-fetched they might seen, but they had been proved right too often to be safely ignored” (Shroud for a Nightingale). For Adam Dalgliesh, “it wasn’t the last piece of the jigsaw, the easiest of all, that was important. No, it was the neglected, uninteresting, small segment which, slotted into place, suddenly made sense of so many other discarded pieces” (The Black Tower).

The result is a clearance rate that over the course of the series takes him from Detective Chief-Inspector to Superintendent to Commander, with his own special squad that investigates crimes of particular social or political sensitivity, as well as a role as special adviser to the Commissioner. Naturally, this does not always sit well with some others. “The Yard’s wonder boy,” grouses one in Death of an Expert Witness; “the Commissioner’s blue-eyed boy,” sniffs another in The Skull Beneath the Skin (1982), continuing, “When the Met, or the Home Office, come to that, want to show that the police know how to hold their forks or what bottle to order with the canard a l’orange and how to talk to a Minister on terms level with his Permanent Secretary, they wheel out Dalgliesh.”

Haters got to hate, right? Dalgliesh knows what he is doing, however, and that “small segment” of the puzzle is usually not motive, either. “Motive was the least important factor in a murder investigation. He would gladly have exchanged the psychological subtleties of motive for a single, solid, incontrovertible piece of physical evidence linking a suspect with the crime” (Death of an Expert Witness); “the detective who concentrated logically on the ‘where,’ ‘when,’ and ‘how’ would inevitably have the ‘why’ revealed to him in all its pitiful inadequacy. Dalgliesh’s old chief used to say that the four L’s—love, lust, loathing, and lucre—comprised all motives for murder” (Unnatural Causes).

The worst of those four? In Death of an Expert Witness, Dalgliesh tells his sergeant what else that old chief told him: “He said: ‘They’ll tell you that the most destructive force in the world is hate. Don’t you believe it, lad. It’s love. And if you want to make a detective, you’d better learn to recognize it when you meet it.’”

Dalgliesh knows what he’s talking about there, too. He’s had many affairs, so he can certainly recognize love, but he keeps it out at arm’s length. He loved his wife and son, they died, and he’s never going to let anything like that destroy him again:

“His grief for his dead wife, so genuine, so heartbreaking at the time—how conveniently personal tragedy had excused him from further emotional involvement. His love affairs, like the one which at present spasmodically occupied a little of his time and somewhat more of his energy, had been detached, civilized, agreeable, undemanding. It was understood that his time was never completely his own but that his heart most certainly was. The women were liberated. They had interesting jobs, agreeable flats, they were adept at settling for what they could get. Certainly they were liberated from the messy, clogging, disruptive emotions which embroiled other female lives. What, he wondered, had those carefully spaced encounters, both participants groomed for pleasure like a couple of sleek cats, to do with love….And the worst of it—or perhaps the best – was that he couldn’t now change even if he wanted and that none of it mattered.” (The Black Tower)

Eventually, it does matter—but it takes him a long time to get there, and it is one of the most intriguing aspects of his evolution throughout the entire series.

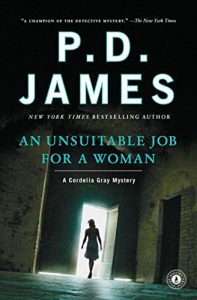

Any discussion of Dalgliesh’s love life has to begin with Cordelia Gray, whose introduction in 1972’s stand-alone An Unsuitable Job for a Woman and then its 1982 sequel The Skull Beneath the Skin broke ground for any current woman professional P.I. you’d care to name. Gray is slight, smart, all of twenty-two years old, and desperately in need of a job when when she joins a scruffy, one-man detective agency run by Bernie Pryde, a former Met policeman and a fount of stories about, and adages by, his former Superintendent, Adam Dalgliesh. Gray’s mother died in childbirth and her father early on decamped to the Continent to become “an itinerant Marxist poet and an amateur revolutionary,” leaving Cordelia to a succession of foster homes and then, by a lucky break, a convent education—she was “muddled” with another C. Gray who was a Roman Catholic—where she did so well she was pointed toward Cambridge, until her father found her again and drafted her, at sixteen, “as cook, nurse, messenger, and general camp follower to Daddy and the comrades” (An Unsuitable Job for a Woman).

Now, here she is, learning the detective trade from Bernie, and by extension, this paragon of a Superintendent, whom, from the stories, she doesn’t like at all because it was he who had been responsible for Bernie getting fired from the Met: “She had devised a private litany of disdain: supercilious, superior, sarcastic Super.”

And then Bernie goes and kills himself—he was dying of cancer, it seems—and wills her the entire agency, such as it is. Her first big case is a doozy (see Essentials below), and in the last chapter of the book brings her into contact with Dalgliesh himself, who has a great many questions about what happened. Cordelia refuses to budge, heeding Bernie’s advice, learned (of course) from Dalgliesh, “If you’re tempted to crime, stick to your original statement,” and he finally lets her go, though not without feeling a bit of a current between them. “I took to her,” he tells the Assistant Commissioner, “but I’m glad I shan’t be encountering her again. I dislike being made to feel during a perfectly ordinary interrogation that I’m corrupting the young.”

He’s wrong about not encountering her again, of course, and we get hints of it in subsequent books: a reference by Dalgliesh to a “love affair” in The Black Tower, a journalist’s comment about their relationship in A Taste for Death (“A beautiful young woman dining with a man over twenty years her senior is always interesting to our readers”), a hope that “one person in particular” would like his new book of poetry in Devices and Desires (“Humiliating but true”). It is in Gray’s equally wonderful second adventure, The Skull Beneath the Skin, however, that we learn the truth. She is thinking of her new flat: “There was only one man she ever pictured there, and he was a commander of New Scotland Yard….But she told herself that the brief madness was over, that at a time of stress and frightening insecurity, she had only been seeking her lost father. There was this to be said for a smattering of psychology: it enabled one to exorcise memories which might otherwise be embarrassing.”

Alas, we never see Cordelia Gray in a book of her own again after Skull. There’s a reason for it—but we’ll deal with that later.

Meanwhile, Dalgliesh’s two other principal amours offer hints about what she may have encountered. In the very first book, Cover Her Face, he becomes attached to a murder suspect, Deborah Riscoe (shades here of Sayers’ Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane, and Ngaio Marsh’s Roderick Alleyn and Agatha Troy). In the next book, A Mind to Murder, his heart leaps when he unexpectedly encounters her at a publisher’s party—he wonders if he should ask her to dinner, but knows, “If she accepted, his solitary life would be threatened. He knew this with complete certainty and the knowledge frightened him.” Nonetheless, he does, she accepts, and in Unnatural Causes, he is agonizing again, this time whether to ask her to marry him. Once again, it is the loss of privacy that makes him dither through a particularly brutal murder case until at last, Riscoe, exasperated, makes the decision for him: She’s been offered a good job in America and she’s taken it. Goodbye.

The other love affair ends more happily as it develops over the span of the last four Dalgliesh novels. Investigating multiple deaths at a theological college in Death in Holy Orders, he meets a grave, beautiful Cambridge lecturer named Emma Lavenham and feels his heart lurch—“Oh God, not that complication. Not now. Not ever.”—but by The Murder Room, it’s become serious indeed, even though in the intervening time, they’ve had only “seven dates arranged, four actually achieved” because of his work, and at the end he writes his marriage proposal to her in a letter and thrusts it into her hand like a schoolboy. The answer is yes, but The Lighthouse brings further complications, and he can’t help but run the litany of failure through his head once again, the phrases from the past—“Darling, it’s been the best ever, but we always knew it wasn’t meant to last;” “What we’ve had has been marvelous, but your job always comes first, doesn’t it?;” “I’ll always love you, Adam, but you’re not capable of commitment, are you?”—but The Private Patient (2008) brings his ordeal, and the series, to a blissful conclusion, James finally granting her detective the happiness he has been so afraid to seek, the very last paragraph, in Emma’s words, expressing James’ own credo:

“The world is a beautiful and terrible place. Deeds of horror are committed every minute and in the end those we love die. If the screams of all earth’s living creatures were one scream of pain, surely it would shake the stars. But we have love. It may seen a frail defense against the horrors of the world, but we must hold fast and believe in it, for it is all that we have.”

Throughout the series, those screams, those deeds, have been as vivid to us as they have been for Dalgliesh and his team—a rotating cast of sergeants and detective inspectors, each of them brought alive as individuals, and none more so than her other most memorable continuing character, a tough, up-by-the-bootstraps young detective named Kate Miskin, with a scathing class consciousness. After interviewing a smug middle class woman, she fulminates:

“She had spent years and energy putting the past behind her…but had she left something of herself behind?…She become middle class. But when the chips were down, wasn’t she still on the side of those almost forgotten neighbors? And wasn’t it the Mrs. Faradays, the prosperous, educated, liberal middle class who in the end controlled their lives? She thought, They criticize us for illiberal responses which they never need experience. They don’t have to live in a local authority high-block slum with a vandalized lift and constant incipient violence. They don’t send their children to schools where the classrooms are battlefields and eighty percent of the children can’t speak English. If their kids are delinquent, they get sent to a psychiatrist, not a youth court. If they need urgent medical treatment, they can always go private. No wonder they can afford to be so bloody liberal” (The Murder Room).

A motherless, illegitimate child from a stinking inner-city high-rise, she knew the police force was her best chance for advancement, a place where her lack of a university degree wouldn’t hold her back, but she still has to use every ounce of her intelligence and determination to climb the ladder. For a long time, the Met didn’t even have women in the detective force; now: “It was a job where people, when they needed you, demanded that you should be there at once, unquestionably, effectively, and when they didn’t, preferred to forget you existed….You kept sane by knowing that hypocrisy might be politically necessary, but that you didn’t have to believe it. You kept honest; there was no point in the job otherwise. You did the job so that your male colleagues had to respect you even if it was too much to expect that they would like you. You kept your private life private, unmessy….You knew how far you could reasonably hope to rise and how you proposed to get there. You made no unnecessary enemies; it was hard enough for a woman to climb without getting kicked in the ankles on the way up” (A Taste for Death).

She does indeed get her fair share of sexism and resentment on the way, but she also gets that “fizz of exhilaration that comes with every new case…this murder with all it promised of excitement, human interest, the challenge of the investigation, the satisfaction of ultimate success” (A Certain Justice) – although she is forced to think uncomfortably, “Someone had to die before she would feel like this.”

You would have thought that she might make a good match for Dalgliesh, and you would have been right. She respects him, is fascinated by him, is always trying to work him out. When asked by a soon-to-be-former beau if she buys his poetry because he’s her boss and she works for him, she says, “No, I read his poetry to see if I can understand him better” (Original Sin), and when asked in the same book by a colleague whose advances she has gently turned down, “If it were AD here with you now, if he asked you to go home with him, would you?,” she says yes. “He asks, “And would it be love or sex?” “Neither,” she replies. “Call it curiosity.”

She is protesting too much, though. Even in The Private Patient, with Dalgliesh’s wedding in the offing and her own further rise in rank assured, she catches a look of fury on Dalgliesh’s face at someone’s high-handed condescension, and thinks to herself, “Emma had never seen that look. There were still areas of Dalgliesh’s life which she, Kate, shared which were closed to the woman he loved, and always would be.”

Kate never lets it show, however, because she is a professional, and that is one of the real pleasures of reading P. D. James. Her police men and women are layered, complex human beings, always competent, sometimes inspired, and James plays fair as she takes us with them through the cases. Her murderers are just as psychologically dense, killing because they must, whether it be for one of the four L’s or because their secrets and lies have caught up to them, often within the family, often stemming from terrible events or betrayals in the past. The criminal violence she portrays is never casual—though she can write a hair-raising action scene with the best of them—but rooted in moral complexity, with a keen sense of what she once described as “the horror of murder, the tragedy of murder, the harm that murder does.”

That is why she is as modern today as she was nearly sixty years ago when she started – but her knowledge was hard-won.

***

Phyllis Dorothy James was born in 1920, the daughter of a tax inspector and granddaughter of a headmaster of a “not very distinguished” boarding school. Her parents were, in her words, “ill-suited.” Her mother was warm-hearted but not that bright, and when James was fourteen, was compulsorily admitted to a mental hospital: “The visits were always painful,” Her father was severe, unaffectionate, and with “a pathological reluctance to part with money.” She and her two siblings were always afraid of him. “It seemed to us, talking quietly together, that our childhood had been lived on a plateau of apprehension with occasional peaks of acute anxiety.”

Her best memories of the time came from when she attended the Cambridge High School for Girls, where she had a favorite English teacher named Miss Dalgliesh, but she had to quit school at sixteen, because her father didn’t want to pay the school fees—he did not believe in inflicting too much education on girls.

From then on, James had to earn her own way in the world. At the age of seventeen, she passed the Civil Service clerical exam and spent eighteen miserable months with the Inland Revenue, then became an assistant stage manager for a Cambridge theatre group, where she met her future husband, Ernest Connor White, whom she married at the age of twenty. An army doctor, he shipped out when the war came, while she scraped by handing out ration books and serving as a Red Cross nurse until he returned, which, unfortunately, was not a happy occasion. He had become mentally ill, a schizophrenic, and he would spend the rest of his life in and out of psychiatric hospitals, sometimes violently so, until his death in 1964 from a combination of pills and alcohol—a suicide, James reckoned.

She quickly realized that it was now entirely up to her to provide for herself and her two daughters, and she began to go to evening classes in hospital administration. Her diploma in hand, she started with clerical jobs in 1949, and for the next nineteen years, rose through the ranks, gathering more and more responsibility on regional hospital boards—including the administration of psychiatric outpatients.

After Connor’s death, she saw an ad to apply to the Home Office, and from 1968 to 1979, she rose there, too, working intensively with the criminal and police departments, including their law departments, the forensic science service, and the juvenile courts.

All of this provided ample material for the books. She could not have written Shroud for a Nightingale, A Mind to Murder, and The Black Tower, she stated, without her background in the health service. Her work for the Home Office informed A Taste for Death, Death of an Expert Witness, Innocent Blood, and several other novels. Her publishing experiences provided vivid observations and stories for Original Sin, Unnatural Causes, Devices and Desires, and The Lighthouse.

And one other aspect of her life suffused nearly all of her books. She was a devout Anglican, often asked to read lessons from the pulpit, and her novels are full of churches, abbeys, cathedrals, rectories, and churchyards, some as a source of peace, others as the setting for spectacular murders. The novels are also full of those who believe, disbelieve, revere, damn, or pointedly ignore God. Dalgliesh lights a candle on the anniversary of his wife’s death, though he does not share her faith (A Mind to Murder); after Bernie Pryde’s death, Cordelia Gray says “a brief convent-taught prayer to the God she wasn’t sure existed” (An Unsuitable Job for a Woman); Kate Miskin declares herself “a natural pagan…I don’t go in for all this emphasis on sin, suffering and judgment” (Original Sin); a colleague of hers explains why it’s difficult to be a Jew, “You can’t be a cheerful atheist like other people. You feel the need to keep explaining to God why you can’t believe in him” (Original Sin); another colleague tells her he studied theology for three years because “actually, it’s a very good training for a police officer. You cease to be surprised by the unbelievable” (A Certain Justice).

James herself, while devout, had her own problems with the Church of England: “I sometimes find it difficult today to recognize the church into which I was baptized. Much of its former dignity, scholarly tolerance, beauty and order have been not so much lost as wantonly thrown away” (Time to Be in Earnest). And in Death in Holy Orders, a distinguished character agrees: “The Church of England will be defunct in twenty years if the present decline continues. Or it’ll be an eccentric sect concerned with maintaining old superstitions and ancient churches. People might want the illusion of spirituality…but they’ve stopped believing in heaven and they’re not afraid of hell.”

There’s nothing like having your own books to provide a bully pulpit.

“I found that if I didn’t settle down and write a novel, I’d end up an old lady telling my grandchildren that I had always wanted to be a writer.”

It was in the late-1950s that she began seriously to get down to work on a novel. She had two teenaged daughters, a mentally ill husband, and a busy job as a hospital administrator, but “I found that if I didn’t settle down and write a novel, I’d end up an old lady telling my grandchildren that I had always wanted to be a writer.” It took her three years to finish Cover Her Face, writing in the early mornings, planning the book on the Tube to work. She put the name P. D. James on the manuscript only because after trying various formulations—Phyllis James, Phyllis D. James, P. D. James—she decided the last one would look best on a book spine.

She had no illusions about making any money on it—she just wanted to get it down on paper. But then she had a lucky break. On a weekend in Kent, she met an actor who’d written books about the theatre, and he suggested she send the manuscript to his agent, Elaine Greene. The day Greene finished reading it, she happened to be sitting at dinner next to one of the directors of Faber & Faber, who was lamenting the recent death of one his crime-writing stalwarts, Cyril Hare. Well, Greene said, maybe I can help you. He read it, bought it, and James stayed with Faber & Faber for the rest of her career.

She still wasn’t making a lot of money, and certainly had no intention of quitting her day job. When she got close to retirement age, however, she decided to leave the Home Office at the end of 1979, “six months before my retirement date, and had carefully calculated that I would be able to live in reasonable comfort until I received my lump sum and pension in August 1980.”

It was in 1980 that she published her eighth book, the stand-alone Innocent Blood. It was modestly successful in Britain—and exploded to #1 in the United States: “At the beginning of the week, I was relatively poor, and at the end of the week, I wasn’t.” She was sixty years old, and never looked back.

Her last novel was published in 2011, at the age of ninety-one, and she died in 2014. She received the CWA’s Silver Dagger three times and was awarded their lifetime achievement award in 1987. She was an Edgar Award finalist three times and was made their Grand Master in 1999. She served as president of Britain’s Society of Authors, a governor of the BBC, a board member of the British Council, a Fellow of both the Royal Society of Literature and the Royal Society of the Arts, and a local magistrate. She received a dozen prestigious honorary doctorates and fellowships, and delighted in speaking at book festivals, interviews, panels, and presentations whenever she could make the time.

In 1983, she received the O.B.E., the Order of the British Empire.

In 1991, she was made a life peer—Baroness James of Holland Park.

But she wore it all lightly—the awards, honors, peerage. She never played the Grand Lady. In 1986, the New York Times published a profile, and here is one of the most telling parts: “If one were creating a character sketch of Phyllis Dorothy James purely from a reading of her books, it would be of a cool, collected figure, friendly enough but probably difficult to know and talk to. But that is not the person who opens the door when you go up the steps and ring the bell of her house. She smiles, arms outstretched in greeting, and says, ‘How lovely to see you, dear.’ Fellow crime writers, asked for a word or phrase to describe her, said ‘hospitable,’ ‘unpretentious,’ ‘marvelously extrovert,’ ‘wonderfully friendly,’ all of which are on the mark. Yet they do not convey her utter lack of affectation and pretension, or the way she radiates good nature and pleasure in whatever she is doing.”

Or, as Ruth Rendell said in one of the many pieces published after James’ death, “She will always live through her books. But for me, she will also be remembered for being such a nice woman.”

___________________________________

The Essential James

___________________________________

With any prolific author, readers are likely to have their own particular favorites, which may not be the same as anyone else’s. Your list is likely to be just as good as min—but here are the ones I recommend.

A Taste for Death (1986)

“If he had indeed been murdered, then the secrets would be told; through his dead body, through the intimate detritus of his life, through the mouths, truthful, treacherous, faltering, reluctant, of his family, his enemies, his friends. Murder was the first destroyer of privacy as it was of so much else.”

The death that Adam Dalgliesh and his new hire, Kate Miskin, are about to investigate is actually two deaths. In the vestry of the magnificent St. Matthew’s Church, its “quiet air tinctured with the scent of incense, candles, and the more solidly Anglican smell of musty prayer books, metal polish, and flowers,” two bodies lie sprawled, their throats both cut, but they could not be more different. One is that of a Baronet and Minister of the Crown. The other is an alcoholic derelict. What could possibly connect these two men? By the Baronet’s hand is a bloody open razor. Is it a murder-suicide? Or just meant to look that way?

Dalgliesh had known the Minister, and liked him, but he is about to know a great deal more, not only about him, but about his family, his colleagues, and the dark secrets that have filled his life in the past and led him to this place at this time with this companion in death.

For Dalgliesh, it is a case filled with sorrow, but for Miskin, it is something else, a chance to prove herself: “If this goes all right, if we get him, whoever it is, and we will, then I’m on my way. I’m really on my way.” After she conducts a successful interview with an overbearing witness, however, she is jolted by a question from Dalgliesh: “Did you enjoy yourself, Inspector?” She replies honestly, because she knows she has no option, “Yes, sir. I liked the sense of being in control….Was the question meant as a criticism, sir?” “No. No one joins the police without getting some enjoyment out of exercising power. No one joins the murder squad who hasn’t a taste for death. The danger begins when the pleasure becomes an end in itself.”

It isn’t the first lesson she’s learned from him, and it’ll be far from the last. For every reason imaginable—the characters, the settings, the prose, the deep dive into the twisted complexities of human psychology (and a truly spectacular ending!)—this is one of James’ best books.

Original Sin (1994)

“There hung over the whole of Innocence House an atmosphere of unease, almost foreboding….Sometimes at the end of the day, when the light began to fade and the river outside was a black tide, when footsteps echoed eerily on the marble of the hall, she would be reminded of the hours before a thunderstorm: the deepening darkness, the heaviness and sharp metallic smell of the air, the knowledge that nothing could break the tension but the first crash of thunder and a violent tearing of skies.”

The quote comes from Mandy Price, a young woman temping at Peverell Press, Britain’s oldest publisher, headquartered in a beautiful Georgian building on the Thames. Innocence House already has a blood-stained history—according to legend, the builder’s wife threw herself from the balcony and her ghost still walks the courtyard—but soon enough Mandy’s premonitions come only too true.

First, it’s just malicious pranks (proofs tampered with, illustrations gone missing), then a just-fired senior editor takes a bottle of pills, and then the real carnage begins. The managing director, Gerard Etienne, is found gassed to death in the archives room, with the office mascot, a stuffed snake, jammed in his mouth. Who wanted him dead? As it turns out, any of the firm’s partners, most of the staff, several authors, and a family member or two. Etienne was planning to upend everything—sell the building, reduce the staff, trim the list—and he was very blunt about it. He was going to get his way, whether anybody else liked it or not.

It turned out, the answer was not.

As Dalgliesh and his team go about their work, however, they discover that even more is going on than all that. These crimes descend from the original sins of the fathers—old outrages, old betrayals, old atrocities, tragedies both public and private. “If God is eternal, then His justice is eternal,” an Anglican nun tells Dalgliesh. “And so is his injustice.”

This is not only an excellent mystery, with James’ usual gallery of complex characters and emotions as deep as the Thames, but it also gives her a fine opportunity to cast a satirical eye on the publishing industry she knows so well. Witness, for instance, this one small sampling, when Mandy spends a couple of days in the publicity department:

“She was introduced by Maggie FitzGerald [the publicity director’s] assistant, to the foibles of authors, those unpredictable and oversensitive creatures on whom, as Maggie reluctantly conceded, the fortunes of Peverell Press ultimately depended. There were the frighteners, who were best left to Miss Claudia to cope with; the timid and insecure, who needed constant reassurance before they could utter even one word on a BBC chat-show and for whom the prospect of a literary luncheon induced a mixture of inarticulate terror and indigestion. Equally hard to handle were the aggressively overconfident, who, if not restrained, would break free of their minder and leap into any convenient shop with offers to sign their books, thus reducing the carefully worked-out publicity schedule to chaos. But the worst, Maggie confided, were the conceited, usually those whose books sold the least well, but who demanded first-class fares, five-star hotels, a limousine and a senior member of staff to escort them, and who wrote furious letters of complaint if their signings didn’t attract a queue round the block.”

An Unsuitable Job for a Woman (1972)

“You can hardly keep the Agency going on your own. It’s not a suitable job for a woman.”

People keep telling Cordelia Gray that, after Bernie Pryde dies and leaves her his detective agency, but growing up in foster homes and then playing nursemaid to her father’s ragtag bunch of pseudo-revolutionaries has given her a strong streak of independence and an instinct for survival. She is tough-minded but sensitive, thinks quickly, reacts even more quickly, and is a realist to her core. She also knows how to lie—in her foster homes, “she had quickly learned that to show unhappiness was to risk the loss of love. Compared to this early discipline of concealment, all subsequent deceits had been easy.” She also has a good memory for the policing knowledge of Adam Dalgliesh, as plentifully quoted to her by her recently deceased boss, Bernie: “Never theorize in advance of your facts;” “Ask yourself what you saw, not what you expected to see or what you hoped to see, but what you saw;” “Get to know the dead person. Nothing about him is too trivial, too unimportant. Dead men can talk. They can lead you directly to their murderers.”

All of this comes in very handy when she is offered her first case. A young man named Mark Callender has been found dead in his cottage in Cambridge, hanging by his neck, a lipstick stain on his mouth, the picture of a nude girl nearby. The verdict at the inquest was that he took his own life while the balance of his mind was disturbed, but his father rejects that completely. “He was a rational person. He had a reason for his actions. I want to know what it was. If I am in some way responsible, I prefer to know. If anyone else is responsible, I want to know that, too.”

When Cordelia starts digging, she has to agree that something is off. The cottage is still as the young man left it, with an untouched dinner on the stove, an unfinished row in the garden, gardening shoes dropped casually by the back door. If dead men could indeed talk, this one wasn’t saying to her, “And then I killed myself.” The police want her not to meddle. His friends want her to leave it alone. His father seems to be hiding something. His father’s assistant is definitely hiding something. Standing in the middle of that room, she senses a presence: “Something here had been stronger than wickedness, ruthlessness, cruelty, or expedience. Evil.”

It isn’t until she is attacked and left for dead that she realizes just how evil.

This is a fine story, told with grace and style, and it makes you immediately want to pick up the second Cordelia Gray novel, The Skull Beneath the Skin. And so you should.

Innocent Blood (1980)

“Someone had watered the flowers overenthusiastically. A milky bead lay like a pearl between two yellow petals and there was a splash on the table top. But the imitation mahogany wouldn’t be stained; it wasn’t really wood. The roses gave forth a damp sweetness, but they weren’t really fresh. In these easy chairs, no visitor had ever sat at ease.”

The observer is Philippa Palfrey, and the details above are a sign of what is to come. Adopted as a child by a prosperous, emotionally distant couple, newly turned eighteen, she has come to a government office to find who her birth parents were, though she has already concocted her own elaborate story: her father was an aristocrat, her mother a parlor maid, so of course she had to be put out for adoption! The truth is much more terrifying.

“We all need our fantasies in order to live,” warns the social worker. “Sometimes relinquishing them can be extraordinarily painful, not a rebirth into something exciting and new, but a kind of death.” And so it proves to be. Philippa’s parents were murderers. Her father raped a twelve-year-old girl, and her mother, Mary Ducton, strangled her. The former died in prison; the latter is about to get released.

Innocent Blood is about how everyone deals with this information, and what happens next: the adoptive parents scolding her (“You don’t really care what your mother did to that girl. It doesn’t touch you. Nothing does.”); the daughter rebelling and renting a London flat for her and Mary to get to know one another, the mother wary (“You aren’t a romantic, are you? You haven’t come here with the idea of proving me innocent? You haven’t been reading too many crime novels?”); the murdered girl’s father meticulously planning to track down Mary Ducton and kill her (as his wife lies dying from cancer, she murmurs, “Better use a knife. It’s more certain. You won’t forget?” “No, I won’t forget.”).

Each of them has a fantasy, each of them is about to undergo a series of shocks, each of them will find themselves in an unimaginable situation as their worlds turn upside down. As we follow their day-to-day lives, their paths coming closer, intertwining and exploding in different ways, the tension ratchets up and the air of foreboding takes your breath away.

“None of us can bear too much reality,” Philippa’s adoptive father warns her. “No one. We all create for ourselves a world in which it’s tolerable for us to live.”

And when that world shatters? Anything can happen—and does. This is James’ masterwork, an astonishing combination of riveting plot, characters, and prose that you will come back to again and again. No wonder this is the book that catapulted her to fame.

___________________________________

Book Bonus: Fiction

___________________________________

Besides Innocent Blood, P. D. James wrote two other stand-alone novels, of vastly different natures.

“Early this morning, 1 January 2021, three minutes after midnight, the last human being to be born on earth was killed in a pub brawl in a suburb of Buenos Aires, aged twenty-five years, two months, and twelve days.” That is the opening line of The Children of Men (1992), a dystopian novel which envisions a world in which the entire human race has become infertile, what that means, and how it affects society. That sounds grim, and it is grim—except for the small band of individuals fighting to save the world. It’s not a book for everybody—James said, “It was traumatic to write and I was glad to return to the less depressing ambience of classical detective fiction”—but it’s written with all of James’ strengths, and the ending is luminous, filled with redemption and hope.

By the way, are you as freaked out by that 2021 date as I am? Just asking.

By contrast, Death Comes to Pemberley (2011) is a sequel to, of all things, Pride and Prejudice. Jane Austen was always P.D. James’ favorite author, often cited in James’ books, and James once even delivered a bravura address to the Jane Austen Society entitled “Emma Considered as a Detective Story,” which can be found in full as an appendix to James’ memoir Time to Be in Earnest (1999).

Pemberley, as Austen fans will recall, is the estate owned by Mr. Darcy, and the book takes place six years after his marriage to Elizabeth Bennet. They have two children, with a third on the way, when her scapegrace sister, Lydia, arrives out of the wind and rain, screaming that her husband, the scoundrel Wickham, is dead in the woods. He isn’t, actually, but when the search party finds him, he is next to the bloodied body of his best friend, and drunkenly babbles what sounds like a confession.

Darcy holds Wickham in very low regard, justifiably so, but capable of murder? Something doesn’t sit right with him, and he sets out to uncover the truth. It’s a wholly charming tale, filled with the spirit of Austen and such epigrams as this one from the always unlikable Lady Catherine de Bourgh, “I have never approved of protracted dying. It is an affectation in the aristocracy; in the lower classes it is merely an excuse for avoiding work.”

“It was great fun to write,” said James. “It really was.”

Also on the fictional side of the ledger are two collections of short stories gathered after her death: The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories (2016) and Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales (2017). Neither is lengthy —there are ten stories, all told—but James obviously had a bang-up time writing them and you will have a bang-up time reading them. Written with humor, elegance, clever plotting, and plenty of twists, each story presents a Golden Age-style puzzle imbued with James’ typical atmosphere and wry characterization, and each one ends with a surprise—sometimes about who did it, but just as often about when, where, and how they got away with it. Dalgliesh even features in two of them, one of them harking back to the days when he was a very young sergeant. Seriously, I can’t recommend these stories enough for any mystery-lover.

___________________________________

Book Bonus: Nonfiction

___________________________________

James wrote three pieces of nonfiction, the first of them in 1971, with a police historian named Thomas A. Critchley. Titled The Maul and the Pear Tree: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders, 1811, it was about a series of murders in London that year—seven vicious deaths that caused panic in the city, which lacked a central police force then. Poring over documents and contemporary accounts, the authors explored the incompetence of the investigation and presented their own theory of what really happened. The New York Times called it “an enthralling story” and “a model demonstration of how to assess fragmentary and often tantalizing evidence,” so for all you true-crime fans, this one is for you.

The other two books were closer to home: Time to Be in Earnest: A Fragment of Autobiography (1999) and Talking About Detective Fiction (2009). The first book is constructed as a diary of her very busy comings and goings from August 1997 through August 1998, but she uses the structure to delve into whatever subjects and pieces of her life she cares to talk about. She draws a veil over some of it—“I shan’t write about my marriage” (although she does)—but the book is bursting with stories, anecdotes, opinions, tutorials, and musings, all written with wit, candor, and a surprising lack of ego. I’ve drawn upon it myself for this piece. If you’re interested in James at all, you’ll find much to like about her “fragment.”

Talking About Detective Fiction, published when she was 89, came about because the head of the Bodleian Library in Oxford asked her to write it and “I was relieved that the subject proposal was one of the few on which I felt competent to pontificate.” The result is an idiosyncratic but always absorbing look at the history of detective fiction, its future, how it works, and why it all means so much to us. There are some especially able examinations of the Golden Age and the virtues and failings of the “Queens of Crime,” Christie, Sayers, Allingham, and Marsh; as well as an all-too-brief foray into the American hard-boiled style. Slim, elegant, and perceptive, it’s a book for the mystery fan—and that’s you, isn’t it?

___________________________________

Movie and Television Bonus

___________________________________

Only two movies were ever made from James’ books, but the many television series more than made up for it (though one in particular left her with a bad taste in her mouth, as you’ll see).

The first movie was a 1982 British version of An Unsuitable Job for a Woman, starring Pippa Guard as Cordelia. It didn’t make much of a splash, but the Thrilling Detective website calls it offbeat and atmospheric, so I wouldn’t mind seeing it some day.

The movie that did make a splash was Children of Men in 2006. Written and directed by Alfonso Cuaron, best known at the time for Y Tu Mama Tambien and a Harry Potter movie, but since, of course an Oscar winner for Gravity and Roma, it starred Clive Owen, Michael Caine, and Julianne Moore, and won excellent reviews. The New York Times said, “It’s the kind of glorious bummer that lifts you to the rafters, transporting you with the greatness of its filmmaking.” I agree with all of that. It won no Oscar nominations, but was nominated for both the Edgar and the Hugo, and won the USC Scripter Award. James shared credit for all of those, and if you look closely, you’ll see James herself in the opening scene, watching the news while holding a dog.

On television, however, almost all of the Dalgliesh novels were made and shown in Britain, and in the U.S. on PBS’s Mystery! series. Roy Marsden starred in ten of them from 1983’s Death of an Expert Witness through 1998’s A Certain Justice, and Martin Shaw starred in 2003 and 2004 in Death in Holy Orders and The Murder Room. These dramatizations started out at six episodes, but by the time of the two Shaw series, they were down to two. “The difficulty is that television drama has become so expensive,” said James. “Everything has to be so cut, so truncated, so changed, that novelists feel that sometimes the essence of a book goes. But I have been luckier than most.” She liked Marsden—“he has height, a beautiful, interesting voice, and certainly presence. He is not my idea of Dalgliesh”—citing Marsden’s mustache and partial baldness, and some mistakes—“but I would be very surprised if he were. This is Roy Marsden’s interpretation of Dalgliesh.”

I watched every one of the shows broadcast in the U.S. and loved them all—to a generation of TV watchers, I imagine Marsden is our idea of Dalgliesh.

The record was much spottier with Cordelia Gray, however. In 1997, an adaptation of An Unsuitable Job for a Woman starring Helen Baxendale was shown in Britain and on Mystery!. James liked it very much and so she had high hopes for what they would do next. What did come next were shows “based on characters created by P.D. James,” and she found them lacking in pace and suspense, while “Cordelia had become ineffectual, dithering, and incompetent.” But that was nothing compared to what happened next. Helen Baxendale had become pregnant, and the producers said the third series would incorporate the pregnancy: “Cordelia would have an affair with an old boyfriend who then disappears to the United States, leaving her, the brave little woman, to cope alone.” James hit the roof. First of all, she learned about it only from an article she read in a magazine at the hairdresser’s. Second, “Cordelia was not the sort of girl to have an affair resulting in a pregnancy.” She protested, offered some alternatives, “but they made it abundantly clear that they neither value nor want any input from me.” She disassociated herself from the series and tried, unsuccessfully, to get the overall title, An Unsuitable Job for a Woman, removed. “They stole my character,” she said. “Cordelia with an illegitimate child is no longer my character.” She had been considering writing another Cordelia Gray novel, but now she simply couldn’t: “It was deeply depressing.”

She had better luck with the three-part adaptation of Death Comes to Pemberley in 2013. Starring Matthew Rhys, Anna Maxwell Martin, and Matthew Goode, among others, it was a stirring and faithful version that pleased James and Austen fans alike.

___________________________________

Meta Writer and Publisher Bonus

___________________________________

“Tricky, that’s what writers are. You have to keep on telling them how wonderful they are or they go to pieces.”

– Original Sin

“What was he like as a person?” asked Dalgliesh.

“Oh, difficult. Very difficult, poor fellow! I thought you knew him? A precise, self-opinionated, nervous little man perpetually fretting about his sales, his publicity, or his book jackets. He overvalued his own talent and undervalued everyone else’s, which didn’t exactly make for popularity.”

“A typical writer, in fact?” suggested Dalgliesh mischievously.

“Now, Adam, that’s naughty. Coming from a writer, it’s treason. You know perfectly well that our people are as hard-working, agreeable and talented a bunch as you’ll find outside any mental hospital.”

– Unnatural Causes

Old Sir Hubert Illingworth had made his brief appearance in the course of [the party], had shaken Dalgliesh sadly by the hand, and had shuffled off muttering under his breath as if deploring that yet another writer on the firm’s list was exposing himself and his publisher to the doubtful gratification of success. To him all writers were precocious children; creatures to be tolerated and encouraged but not overexcited in case they cried before bedtime.

– A Mind to Murder

The new management promoted their poets vigorously, perhaps seeing the poetry list as a valuable balance to the vulgarity and soft pornography of their best-selling novelists, whom they packaged with immense care and some distinction, as if the elegance of the jacket and the quality of the print could elevate highly commercial banality into literature. Bill Costello, appointed the previous year as Publicity Director, didn’t see why Faber & Faber should have a monopoly when it came to the imaginative publicizing of poetry, and was successful in promoting the poetry list despite the rumor that he never himself read a line of modern verse.

– Devices and Desires

The guest list had chiefly comprised their most prestigious writers in the main categories, a ploy which had added to the general atmosphere of inadvertence and fractionized unease: the poets had drunk too much and had become lachrymose or amorous as their natures dictated; the novelists had herded together in a corner like recalcitrant dogs commanded not to bite; the academics, ignoring their hosts and fellow guests, had argued volubly among themselves; and the cooks had ostentatiously rejected their half-bitten canapés on the nearest available hard surface with expressions of disgust, pained surprise, or mild, speculative interest.

– Devices and Desires

___________________________________

Meta Crime Writers Bonus

___________________________________

The Cadaver Club is a typically English establishment in that its function, though difficult to define with any precision, is perfectly understood by all concerned….The Club is exclusively masculine; women are neither admitted as members nor entertained. Among the members there is a solid core of detective novelists, elected on the prestige of their publishers rather than the size of their sales….The exclusion of women means that some of the best crime writers are unrepresented, but this worries no one; the Committee take the view that their presence would hardly compensate for the expense of putting in a second set of lavatories.

– Unnatural Causes

It was strange how little she knew about a real police investigation despite Bernie’s tutelage. It had already struck her that their legal powers were a great deal less extensive than a reading of detective fiction might suggest.

– The Skull Beneath the Skin

It was only in fiction that the people one wanted to interview were sitting ready at or in their office, with time, energy and interest to spare. In real life, they were about their own business and one waited on their convenience.

– An Unsuitable Job for a Woman

“He made a fortune out of that best-seller he wrote. Autopsy. He’s A. K. Ambrose. Didn’t you know?’

Cordelia hadn’t known. She had bought the paperback, as had thousands of others, because she had got tired of seeing its dramatic cover confronting her in every bookshop and supermarket and had felt curious to know what it was about, a first novel that could earn a reputed half a million before publication. It was fashionably long and equally fashionably violent, and she remembered that she had indeed, as the blurb promised, found it difficult to put down, without now being able to remember clearly either the plot or the characters.

– The Skull Beneath the Skin

“You should read detective fiction, Adam. Real-life murder today, apart from being commonplace and – forgive me – a little vulgar, is inhibiting of the imagination. Still, moving the body would be a problem. It would need considerable thought. I can see that it might not work.”

Ackroyd spoke with regret. Dalgliesh wondered if his next enthusiasm would be writing detective fiction. If so, it was one that should be discouraged.

– The Murder Room

___________________________________

Meta Golden Age Bonus

___________________________________

Sipping her whiskey, Blackie reflected that there was something strangely reassuring about Joan’s uninhibited interest in and speculation about the crime. Not for nothing was there those five shelves of crime paperbacks in her bedroom, Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, Josephine Tey, and the few modern writers whom Joan considered fit to join those Golden Age practitioners in fictional murder….She stared into the leaping flames from which the image of Miss Marple seemed to rise, handbag protectively clutched to her bosom, the gentle wise old eyes gazing into hers, assuring her that there was nothing to be afraid of, that everything would be all right.

– Original Sin

[On the resemblance of a manservant to a certain similarly-named manservant of Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey] Munter’s disapproval came over the line as clearly as his carefully controlled irony. He was adept at judging just how far he could safely go, and since his veiled insolence was never directed against his employer, Gorringe was indulgent. A man, particularly a servant, was entitled to his small recalcitrant bolsterings of self-respect. Gorringe had noted early in their relationship how Munter’s persona, modeled as it was on Jeeves and his near namesake Bunter, became markedly closer to parody when any of his carefully contrived domestic arrangements was upset. During Clarissa’s visits to the castle, he became almost intolerably Bunterish. Relishing his manservant’s eccentricities, the contrast between his bizarre appearance and his manner, and totally uncurious about his past, Gorringe now hardly bothered to wonder whether a real Munter existed and, if so, what manner of man he might be.

– The Skull Beneath the Skin

[And then two literary characters in a possible suspect’s books strikingly similar to Lord Peter Wimsey himself and his friend and frequent colleague, Detective Inspector Charles Parker] [Inspector] Briggs, who was occasionally called Briggsy by the Honorable Martin in an excess of spurious camaraderie, had a humility…Despite his eminence at the Yard, Briggsy was always happy to play second fiddle to Carruthers, and so far from resenting the Honorable Martin’s interference with his cases, made a practice of calling him in when his special expertise was required. Since Carruthers was an expert on wine, women, heraldry, the landed gentry, esoteric poisons, and the finer points of the minor Elizabethan poets, his opinion was frequently invaluable….Inspector Briggs’ suspects, if required to make statements – which was seldom – made them in the comfort of their own homes, attended by obsequious policemen and with Carruthers present to ensure, in the nicest possible way, that Inspector Briggs kept his place.”

– Unnatural Causes

Kate said, “She found Treeves’ body, remember.”

“What’s that to do with it? The diary note is explicit. She didn’t remember that incident from her past when she saw the body, she remembered when Surtees brought her some leeks from his garden. It was then that things came together, the present and the past.”

Kate said, “Leeks – a leak. Could it be a play on words?”

“For God’s sake, Kate, that’s pure Agatha Christie!”

– Death in Holy Orders