“You any tougher than you look?”

“Hell yes! At least, I used to be.”

“I used to be. We all used to be.”

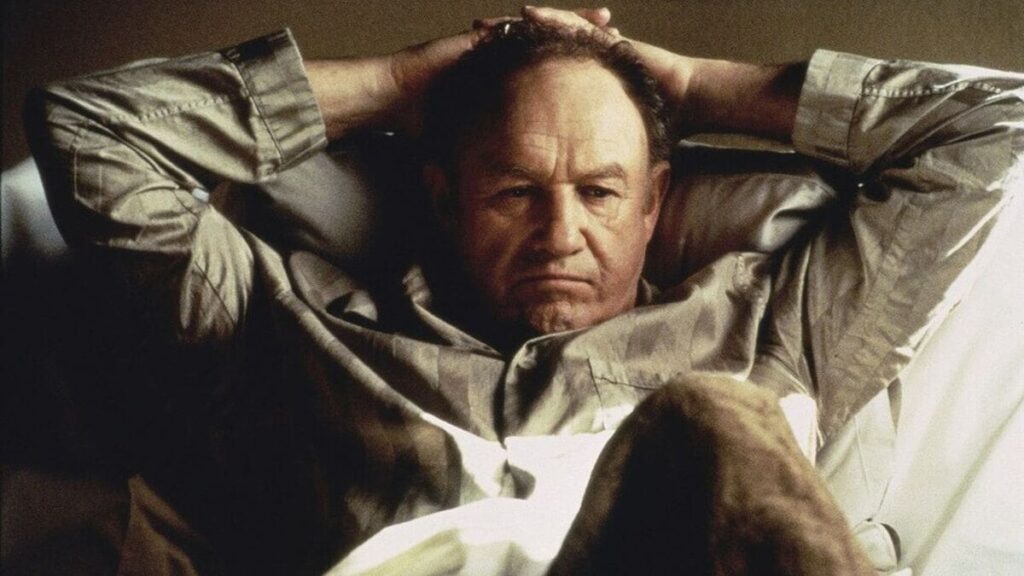

Harry Ross (Paul Newman) was, as he describes it, a cop for twenty years, a PI for five, and then a drunk. When an errand to retrieve the wayward daughter of film stars Jack and Catherine Ames (Gene Hackman, Susan Sarandon) goes awry due to Harry’s inattention and subsequent injury, the Ameses allow him to recuperate in an apartment above the garage in their Art Deco mansion. Two years later, Harry remains, having settled into a cushioned role as a handyman and sort of kept friend to Jack. His mutual attraction with Catherine adds a pinch of spice to bland days of playing gin and fixing appliances.

Jack asks Harry to deliver a package—contents unspecified, reasons eluded. “It’s not blackmail,” Jack claims, so we and Harry know immediately that it must be. Harry allows himself to be persuaded. Soon, Harry is dodging bullets fired by a mortally wounded man and tangled in a mystery that involves both Jack and Catherine as well as a few players from Harry’s own rocky past: A PI associate eager to work with Harry again despite lacking any discernible skills. The would-be Lothario who had spirited the Ames’s daughter Mel off to Mexico and earned a prison stretch as a result. And watching from the periphery is Harry’s closest friend, an ex-cop turned studio security chief named Raymond Hope (James Garner), who has his own history with the Ameses.

“Don’t you ever get tired of the beautiful people? Doesn’t it ever bother you that the Jacks and the Catherines of this world can do as they please, ’cause it’s always guys like you and me who clean up after them?”

Twilight (1998) can be imagined as the closing chapter to a loose trilogy. Paul Newman had notably played a private investigator twice before, in films adapted from Ross Macdonald novels. Macdonald’s Lew Archer was redubbed Harper for the eponymous 1966 movie and the 1975 sequel The Drowning Pool. You don’t have to squint hard to see Twilight‘s Harry Ross as Harper another twenty years along. Ross is a kinder person than Harper. Still quick to spot others’ faults but more forgiving in pointing them out. Harry has the cautious mien of a reformed cynic, a person who once believed he’d seen everything and now hopes to discover something new worth saving.

Harry tries to help young Mel, angry as he is at her role in his humiliation. Harry tries to help everyone. Jack, Catherine, the blackmailers who are in way over their limited heads, the sidekick who wants to dive head-first into sordid PI work. Harry warns them all, encourages them to cut their losses and get out. Some are smart enough to listen. Some become dead. Lew Harper wouldn’t have cared, except that he’d not caught the culprits sooner. Harry Ross feels the tragedy.

“What’s that perfume you wear? The reason I ask…it was still in the air when I got there.”

“Harry, a lot of women wear Bal à Versailles.”

“It smells different on them.”

For Twilight, Newman re-teamed with director Robert Benton and writer Richard Russo on the heels of the trio’s shared success with Nobody’s Fool. Based on Russo’s novel, Fool had been critically lauded and collected a handful of awards and nominations, and nearly doubled its modest twenty-million-dollar budget. Paramount allotted the same budget to Twilight. Benton enlisted famed composer Elmer Bernstein to create a lush score.

The bench strength of the cast is astounding. Its four leads require only one name: Newman, Sarandon, Hackman, Garner. The secondary cast is loaded with veteran actors and newer faces now instantly recognizable: Reese Witherspoon, Stockard Channing, Liev Schreiber, John Spencer, Margo Martindale, Giancarlo Esposito. Even the legendary M. Emmet Walsh turns up in a role that doesn’t have a single line (but whose gun says plenty). Counting the director, writer, and composer, the team boasts nine Oscars, twelve Emmys, fifteen Golden Globes, nine SAG Awards, a couple of Tonys, a Pulitzer Prize, and even an Edgar Award—won by Benton for writing another PI screenplay, The Late Show.

Benton shot almost nothing on sets, adding textures that weren’t available in the soundstage heyday of detective films. Bookend scenes are at the actual Hollywood Station of the LAPD, with real cops as extras and movie posters on the walls. The seedy houses and apartments of LA’s further reaches have authentic grunge. A 1920s manse built for Delores Del Rio by husband Cedric Gibbons (designer of the Oscar statue) becomes the luxe abode of Catherine and Jack. Raymond Hope lives in a small Modernist marvel hovering on stilts above the smog, a house designed by John Lautner in 1948. And one of the many unfinished projects of Lautner’s mentor, Frank Lloyd Wright, stands in for the remote ranch home of the Ameses.

So why, with all this pedigree and attention to detail, did Twilight fail with critics and audiences?

“Life has worked out for you in ways that it doesn’t for most people. I think people like you get used to having it work out for you and after a while, you begin to think you’re entitled to all the things that you’ve got.”

The film’s timing didn’t help. Twilight had the bad luck to open on the same day as two other crime-related movies with radically different tones: The Big Lebowski, and the Fugitive sequel U.S. Marshals. Twilight placed tenth in box office receipts for the month. Lebowski earned only a fraction more, and, while successful, the Tommy Lee Jones thriller came a distant second to the nautical juggernaut that had swamped all competition since December—Titanic.

Twilight breaks no new ground in its structure, either. After the almost-comedic prologue—setting up a running gag involving the location and subsequent severity of Harry’s wound—Twilight opens where many noirs have before: in a police interrogation room, the lead character’s statement forming the voiceover that will guide us through the picture. Story elements are copped from The Big Sleep, Murder, My Sweet, and numerous other classics.

Even the names confess to cribbing. Harry Ross, as in Macdonald. Raymond (never Ray) Hope, as in Chandler. Benton and Russo are being obvious in their influences and plotting, which underlines the key distinction between Twilight and its forerunners: These aren’t people in their prime we’re watching this time. They, and the film, don’t move at quite the same speed.

That significance escaped or was outright derided by most critics. “Geezer noir” sniffed the LA Times. Roger Ebert, while praising Newman’s performance, couldn’t see the point of the film. Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly said, “Twilight plods and pokes along mercilessly”. Those opinions weren’t universal, but they were enough to cripple an already sluggish arrival in theaters.

“Harry. You haven’t said you’re sorry.”

“You haven’t been listening.”

Perhaps critics missed Benton’s intentions. Twilight‘s characters are older, yes, but also wiser. The script has every bit of the sharp dialogue fans of the genre expect. Its slower pace is a plus. If a crime thriller with multiple homicides can be considered a hang-out movie, Twilight is a good contender. It would be a pleasure to shoot the shit for a few hours with Channing’s dry-witted police lieutenant or Garner’s growling studio fixer.

Twilight‘s original title was The Magic Hour, after the filmmaking term for the time of day when the sun is low and its light softer and more flattering. That working title would have suited a story with two movie stars as lead characters. But Twilight is more fitting, any later comparisons and confusion with teen vampire movies aside. The primary characters are in the waning days of careers, of lives, and of long-held secrets. Each is acutely aware that darkness is fast approaching. Jack is battling cancer for the second time. Catherine is younger and healthier than the two men in her life, but women in Hollywood are held to a different standard of success. Just maintaining the status quo requires desperate measures. And Harry knows he’s lost a step in an unmerciful profession. He should take his own advice and get out while he can.

Benton knew who he had in his cast, knew the audience would know it, too. Each actor brings history. Paul Newman’s long line of flawed protagonists fighting impossible odds bleeds into Harry Ross. Susan Sarandon is the sexually liberated woman smarter than the men chasing her. James Garner’s Raymond Hope might be Jim Rockford with slipperier ethics. Gene Hackman had played so many tough guys that we never doubt Jack is still formidable.

“I remember a movie your husband made. He shot twelve guys with a six-shot revolver. I ain’t gonna argue with that kind of marksmanship.”

The costuming tells us who these characters are. Harry starts the main story in a pastel pink shirt—a gift from Jack. A pale tone for the softer life Harry has accepted. By the end, Harry is still in the same deep-pocketed brown coat and khakis and white tennis shoes of a handyman, but the shirt has switched to blood red. The more vibrant color speaking to Harry’s rekindled righteousness and the trouble he’s found himself in. Sarandon’s Catherine is swathed in black or rich creams, immaculate. And always with a cigarette, her smoky ambiance another callback to the days of classic noir. Hackman, as the ailing Jack, is often a little overdressed, as if fooling himself that he might be called back onto a movie set at any moment. Garner wears earth tones a few shades darker than Newman’s.

Reflections real and figurative abound. The glass walls of the Ames home and Raymond’s aerie show their inhabitants from multiple angles. The Ames house is filled with pictures of Catherine, a Deco shrine to her career and her narcissism. Our final sight of Jack is of him watching one of his old films, admiring his young and vital self.

The most telling reflection is Garner’s Raymond, a warped mirror image of Harry. Raymond is the one who took Harry in at his lowest, cleaned him up, and got him work with the Ameses. Harry, we know without being told, would have done the same for Raymond. Both are former cops, both employed to clean up the messes of people in higher standing. Perhaps their only difference being the layers of dirt each is willing to scrub. Harry suspects but doesn’t know how far Raymond might go. Raymond sees Harry more clearly, and the risk his friend presents. Is it any surprise the two men have the closest relationship of anyone in the film?

“Did it ever strike you this is a lousy way to make a living? You start out thinking you’re gonna win a few, but mostly it’s…it’s just like tonight. Watching people run out of the little bit of luck that they got left.”

Harry carries a trainload of guilt for his past mistakes and losses—the full measure of which we learn only late in the film, in an almost throwaway line that lands like a sucker punch to the gut. Having surrendered so much, his sudden bulldog determination to regain his pride and follow the truth wherever it leads surprises even him.

Loyalty and its dark sibling corruption are Twilight‘s themes. Is Harry indebted enough to Jack to bury his famous friend’s secrets? Is Jack playing on Harry’s goodwill? Does Catherine truly love her husband, or Harry, or is she manipulating them both to her own purpose? Near the end, Harry puts a friendship to the ultimate test by the same method as Lew Harper had three decades before, by turning his back and risking death. Only this time, our hero keeps one eye on the reflection in the glass. Older, and wiser.

You can be corrupt, you can be cynical, Twilight says, and you might come out ahead. For the rest of us, integrity is our best shot. The darkness is inevitable, but while there’s light in the sky, there’s still time to make things right.