Every picture tells a story.

If you don’t believe me, just ask Rod Stewart. Sir Rod practically coined the phrase in 1971. He liked it so much he used it for both the title of his third solo record on Mercury and for the title of the album’s opening track. The album was a breakthrough for Stewart and a breakaway from the blues-based music he was performing with the Jeff Beck Group. The songs on the album were more personal to the singer and Every Picture Tells a Story is one of Stewart’s most personal tracks. Although he shares credit for the song with his mate Ronnie Wood, the lyrics are pure Rod Stewart.

The song starts with the singer looking at himself in the mirror and he does not necessarily like what he sees:

Spent some time feeling inferior

Standing in front of my mirror

Combed my hair in a thousand ways

But I came out looking just the same.

The singer can change hair styles, change outfits, even change his name, but the man, or woman, in the mirror remains the same. No matter how many times, and how many different ways you try to look at yourself in the mirror, you can’t change the person you see.

The pictures you see in the mirror tell a story. But it may not be the story you want to tell.

I was pondering such happy thoughts while studying a picture from my perch inside The Last Bookstore at Spring and Fifth in the old Crocker Tower in downtown Los Angeles. I was listening to the winter rain pound against the graffiti-tagged windows of the old bank building. It rained a lot this past winter in L.A. and when it rains in Los Angeles, everyone stays inside. Everyone except the taggers. Nothing keeps the taggers off the streets of downtown Los Angeles; they are more dependable than the U.S. Postal Service. And considerably more creative.

But I was not reading the graffiti on the windows. I was looking at a picture on the cover of the book I was holding. And I was thinking it was a picture with a story to tell. Maybe more than one.

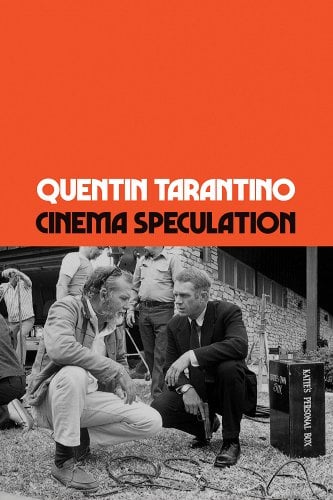

The picture I was studying was the photograph on the cover of Cinema Speculation, Quentin Tarantino’s first work of nonfiction, a mash-up of film criticism and coming-of-age memoir. The hardcover edition of Cinema Speculation has a clean orange and black design that invokes both the late-period paintings of Mark Rothko and the 1970s home ice uniforms of the Philadelphia Flyers. The front and back covers of the book are mercifully free of blurbs and other nonsense. All we see is the artist’s name, the title of his book and a stark photograph announcing the artist’s intentions.

The photo is a black and white still of Steve McQueen and Sam Peckinpah taken during a break on the set of their 1972 crime caper film, The Getaway. McQueen, in costume as master thief “Doc” McCoy, is wearing a trim, black suit, white shirt and tie. The cameras are not rolling, but McQueen still has McCoy’s handgun, a black metal semi-automatic, resting comfortably in his right hand. He looks ready for someone to call “action.” Peckinpah, in denim and fringe, has his sunglasses perched on top of his head, and a goatee on his chin.

Peckinpah is saying something. McQueen is listening intently.

The pair are crouched down in the foreground of the photo like two generals plotting their next move on the battlefield. Or like two arch-criminals plotting their next caper.

At their feet are the cables and cords that supply the power to their plans. Behind them, loitering in the background, are a handful of their foot soldiers, or henchmen, awaiting the outcome of their captains’ council.

Next to McQueen and Peckinpah is a mysterious waist-high black box with the inscription, or maybe it’s a warning, “Katie’s Personal Box” on one side and “Katie’s Own Box” on another side. On closer inspection, maybe it says, “Katie’s Gun Box.”

If I learned that Katie’s Box was full of armaments, I would not be surprised.

Exactly why Tarantino chose this photo for the cover of his first work of film criticism, he does not say. But I can speculate that it was the meticulous Tarantino, and not an art director at Harper’s Publishing House, who chose the cover photo. Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation, like Stewart’s Every Picture Tells a Story, is a very personal work of art and the cover photograph Tarantino chose is a near-perfect distillation of what the author wants to say about some films that have mattered to him since he was young.

Cinema Speculation is devoted to the films that influenced Tarantino during his formative years as a filmgoer from 1968 to 1981, when he was growing up in Torrance, California and catching movies on screens all over Los Angeles County. The chapters are built around a specific film. From classic films like Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, written by film critic turned screenwriter, Paul Schrader, to lesser known films Tarantino admires like Sylvester Stallone’s Paradise Alley and Rolling Thunder, directed by John Flynn from a screenplay co-written by Paul Schrader, who makes frequent appearances in the Tarantino cannon, and Heywood Gould, who does not.

As he does in his films, Tarantino frequently shifts narrative perspective in the book. He shifts gears on a dime, from a wide-angle view that put me in the audience sitting in a theater next to a young Tarantino, to a close-up view that took me inside the film. In the chapter devoted to The Getaway, there are times when I felt like I was on the set of the film, leaning on Katie’s Box and looking over McQueen’s shoulder as he talks to Peckinpah.

As I peeled away the layers of personal, historical, theatrical, and critical data that Tarantino serves up, I found the sentence that provides context for the scene captured in the photo. While describing the real work of a film director, Tarantino lifts the curtain to tell us that “solving the problems, both large and small, of your actors – lead actors especially – is the job of a film director.”

The emphasis is Tarantino’s.

In the photo on the cover of Cinema Speculation, we will never know whether Peckinpah was solving a large or a small problem for McQueen. But after reading the book, I can make the informed speculation that the problem Peckinpah is trying to solve has something to do with the gun McQueen is holding in his hand.

Walter Hill, who worked closely with Peckinpah to adapt the screenplay for The Getaway from Jim Thompson’s source material, told Tarantino that McQueen “knew a lot about firearms and was an expert at handling them.” According to Hill, the nature and quality of the guns that his character Doc McCoy would handle in the crime film were so important to McQueen that “Steve decided to cut the cord” on the original director that Paramount hand-picked for the film.

Robert Evans, the swashbuckling head honcho at Paramount Studios wanted his friend Peter Bogdanovich to direct The Getaway. Maybe it was because Bogdanovich was a very hot property in Hollywood in 1971. Or maybe it was because Bogdanovich, with his ascots and affectations, looked and acted like Robert Evans’ little brother.

Whatever the reason, it only took one meeting for McQueen to put the kibosh on Bogdanovich. In that initial story conference, Bogdanovich brushed aside his star’s detailed questions about the director’s thoughts about the kinds of guns his character would use. Revolvers or automatics? Shotguns or rifles? Guns were just props to Bogdanovich and he told McQueen not to worry about the props.

Bogdanovich brushed McQueen’s questions aside.

And then McQueen brushed Bogdanovich aside.

Bogdanovich had broken Tarantino’s golden rule. Rather than “solving the problems” for his star actor, he was making problems for McQueen, one of the biggest box office stars in the world.

To McQueen, the guns his character Doc McCoy would handle in the film were not just props. He saw them as a physical extension – or manifestation – of character. And Tarantino, in both his chapter on The Getaway and his chapter on Bullitt, makes it clear that the physical manifestation of character to McQueen was more important to him than the words his character spoke on screen. According to Tarantino, the guns he carried and used as Doc McCoy and the clothes he wore in Bullitt, the black turtleneck and shoulder-holster, were the choices the star made to illustrate his character for the audience. Tarantino explains that McQueen, working with his first wife Nellie, his closest partner in creating McQueen’s iconic persona, would cut McQueen’s dialogue from the script or transfer his dialogue to a supporting actor. McQueen instinctively knew that what mattered to his audience was what he was doing in the film, not what he, or anyone else, was saying. No matter who was talking in the scene, the audience would be watching McQueen.

Tarantino’s explanation of McQueen’s celluloid star power is convincing. It brings to mind Brad Pitt’s laconic performance in Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Pitt does not have many lines in the film, but when he is on the screen, the audience is always looking at him. His sunglasses. His T-shirt. His tool belt. They are all choices that illuminate Pitt’s character on screen.

When McQueen brushed Bogdanovich from the picture, that opened the door for McQueen’s friend Sam Peckinpah to take over. Peckinpah and McQueen both desperately needed a hit film because their last picture together, Junior Bonner, bombed at the box office.

The chemistry between director Peckinpah, star McQueen and writer Hill, and the last minute addition of the woman who would soon become Steve McQueen’s second wife, Ali MacGraw, came together to turn The Getaway into what Tarantino calls a “massive hit” for everyone involved. A film that was so popular at the box office in 1972 and 1973 that Tarantino saw it four different times during its theatrical run – twice in Westchester near LAX, once in Marina Del Rey, and once while visiting Tennessee with his Mother. (Tarantino, we learn, is very obsessive about the precise details of every one of his moviegoing experiences.)

The most astute observations Tarantino has about The Getaway relate to Ali MacGraw’s role in the film and her impact on the success of the film. Tarantino complains that MacGraw’s role in the film has been unfairly criticized. It is not because he thinks she is a naturally gifted actress but because the chemistry between MacGraw and McQueen in the film is so palpable that Tarantino believes it elevates, or maybe translates, the film from a convincing crime caper film to an even more convincing love story.

MacGraw’s presence is so singularly important to The Getaway that Tarantino frames his chapter on The Getaway with a quote about the film from Ali MacGraw. It is one of the most insightful statements ever made about the film:

“The imprint of Steve McQueen, and Sam Peckinpah, and the stuntmen, and the location, and the kind of maleness of it all, was so exciting . . . and it’s never been duplicated.”

Take another look at the photo on the cover of the book and you can see exactly what MacGraw means by “the maleness of it all” on the set of The Getaway. That may be a clue as to why the feline presence of MacGraw was so important to the success of the film.

The Getaway is a good film without MacGraw. It is a great film because of MacGraw.

***

I mentioned earlier that the photo on the cover of Cinema Speculation has more than one story to tell.

It also tells a story about me.

That’s because Tarantino did not introduce me to the photo. I was introduced to the photo of McQueen and Peckinpah in 1978 by Augustus Blasé Jr., Associate Professor of American Film Studies at Clark University and, according to him, “the foremost expert on Samuel Peckinpah east of the Mississippi.”

Professor Blasé tacked the photograph to the wall behind my desk in the basement of the Dr. Robert H. Goddard Memorial Library on the Clark campus in my hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts. The Bob, as we all called the library, was named after Worcester’s favorite son, Dr Robert Hutchings Goddard, who, as we were taught from grade school on, was the “father of modern rocket propulsion” and the “grandfather of the NASA Program.

Goddard was a man to be admired.

Dr. Goddard may also have been father of the V-2 rocket and Brennschluss, and the grandfather of Dr. Strangelove and Mutually Assured Destruction.

But we weren’t taught any of that.

Blasé taught a film class at Clark that he called American Catharsis: The Films of Sam Peckinpah. I was in my last year of high school in Worcester and my best friend Charlie and I signed up for the class as “independent study.”

Growing up in Worcester in the ‘70s, I had never seen a Peckinpah film. They had been effectively banned in our Cradle of Liberty, Worcester County. In 1971, the Archdiocese lodged a formal obscenity complaint against the Paris Cinema which was planning to screen Peckinpah’s controversial Straw Dogs, starring a very sweaty Dustin Hoffman and the sublime Susan George. In 1971, the Archdiocese carried a lot of water in town, and the Worcester City Manager promptly instructed the Police Department to confiscate the print of the film before opening night. Our sovereign local police force, not generally known for their enthusiasm, went after this assignment with vigor. They tore the theater’s front doors from its hinges, smashed the projector room, and ripped up the seats.

However, in service of their collective zeal, the coppers actually forgot the object of their raid and left the trashed Paris Cinema without confiscating the film print.

The owner of The Paris took the print home for safekeeping.

Blasé used the auspices of Clark University to collect prints of every Peckinpah feature film, including the print saved by the owner of The Paris. In the fall semester of 1977, he debuted American Catharsis: The Films of Sam Peckinpah, using a screening room at the Bob as a classroom.

My friend Charlie and I attended every Peckinpah screening at The Bob.

Religiously.

When the class ended, Professor Blasé hired me as a research assistant and I spent the spring semester helping him archive the Peckinpah Collection he was surreptitiously building in the basement of The Bob. It was on a wall of my basement office where I tacked up the photo of McQueen and Peckinpah that graces the cover of Cinema Speculation. I found it in Blasé’s archive. I liked it so much he tacked it to the wall behind my desk.

I was obsessed by the physical chemistry between MacGraw and McQueen and maybe I was a little bit in love with Ali MacGraw.

I watched The Getaway over and over on a Moviola that Professor Blasé purloined for the Peckinpah Archive. With Professor Blasé’s encouragement, I used my office in the basement of The Bob to write my senior dissertation about The Getaway. I focused on the raw power of the most important scene in the film.

I am talking about the scene between Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw set in the burnt out husk of an abandoned car among the smoldering ruins of a garbage dump. Where the couple have run to get away from their pursuers.

It’s here where McQueen and MacGraw reach their breaking point. Here where they decide they have to have it out once and for all. Here where they choose if they are going ahead together or if they will go it alone.

In this very lonely place, Carol and Doc McCoy, MacGraw and McQueen, decide to stick together “no matter what.”

No matter what.

Peckinpah, Hill, McQueen and MacGraw had found a way to dramatize a concept I describe as “American Existentialism.”

You can only judge the value of something in terms of how much life you had to spend to obtain it. The true value a thing has, including a thing called love, is the cost you paid for it, not in cash, but in your blood, your sweat, and your tears.

In The Getaway, we witness the heavy costs, the blood, the sweat and the tears, that Carol and Doc McCoy have paid for their love. When they decide to stick together “no matter what” you believe them.

Because they have earned it.

I called my paper The Last Love Story. It was the first thing I had ever written on my own. My first creative act.

Professor Blasé liked my paper so much he submitted it for the University’s annual creative writing award without telling anyone I was in high school. When the paper won the award, a prep school swan from Phillips Academy ratted me out. The award was taken away from and given to The Prep School Tattler.

I also lost my privileges at the Bob and access to the Peckinpah Archive.

Years later, I read in the New York Times that The Prep School Tattler had been charged with insider trading by the United States Attorney in Manhattan. Mention was made that bail was set at one million dollars.

No mention was made of the creative writing award.

Forty-five years have passed since I filed The Last Love Story, portentous title and all. These days, I don’t think about Peckinpah, Blasé, existentialism, or The Bob as much as I did then.

But that does not mean I have forgotten.

***

When I was looking at the picture on the cover of Cinema Speculation, the stories came roaring back to me.

And I did some speculation of my own.

In Cinema Speculation, Tarantino does more than talk passionately about the movies that matter to him. The most personal parts of the book are the chapters where he settles old accounts and thanks two people who helped make him the man he is today.

The first tribute is for Kevin Thomas, who Tarantino describes as the “second string” movie critic at the Los Angeles Times when Tarantino lived his life according to the L.A. Times movie listings. Tarantino considered the “first string” movie critics of the L.A. Times, the reviewers who got all the posh assignments, to be “laughing stocks.” Kevin Thomas reviewed the genre films that Tarantino loved and he considered Thomas’ reviews essential reading.

Tarantino sums it up like this:

“In the end, what made Kevin Thomas so unique in the world of seventies and eighties film criticism, he seemed like one of the few practitioners who truly enjoyed their job. I loved reading him growing up and practically considered him a friend.”

The second tribute is even more personal. Tarantino devotes a chapter to a man named Floyd Ray Wilson. He does not know where Floyd Ray Wilson is today, or even if he is alive. Floyd was a friend of Tarantino’s mother who rented a room from her to help the Tarantino family make ends meet. Floyd was something of a raconteur who could drive young Quentin to the movies around town and escort him into the R-rated films he wanted to see. Even more importantly for young Quentin, Floyd Ray Wilson loved to talk about the movies they saw together.

Tarantino credits Floyd Ray Wilson, an African-American man, for inspiring him to think about the scenario that Tarantino would eventually – years later – turn into his 2012 feature film, Django Unchained. Tarantino also thanks Floyd for encouraging him to write, to create.

“But even more important than any one script was having a man trying to be a screenwriter living in my house. Him writing, him talking about his script, me reading it, made me consider for the first time writing movies. . . . due to Floyd’s inspiration I tried writing screenplays. I usually never got that far. I think page thirty was by far the furthest I ever got. But I tried. And eventually I succeeded.”

Tarantino, like one of the heroes of his youth, Sylvester Stallone, came, as Tarantino puts it, “from so far out of Hollywood that I may as well have been from the fucking Yukon.” When they started, the studio doors were closed to both Stallone and Tarantino. They were nobody. And nobody returned their calls. But they looked around at the quality of films being made in Hollywood and decided, in a quote from Stallone that Tarantino adopts in Cinema Speculation, “I could do at least as good as that.”

If that’s not the ultimate “outsider’s creed,” then I don’t know what is. When the Powers that Be won’t let you in the front door of the arena, then you have to go around back and find a way to sneak in.

Tarantino tips his hat to the outsiders and “second string Samurai” like Kevin Thomas and Floyd Ray Wilson because they inspired him to follow his star. They encouraged him to create when no one else would.

I am inspired to do the same for Professor Blasé, my mentor, and The Bob, an oasis in the drab post-industrial sameness of the city I grew up in. In Worcester, Massachusetts in the late 1970s, no one encouraged anyone to do anything except conform. And no one expected anything creative from you at all.

Except Professor Augustus Blasé Jr.

Wherever you are Gus Blasé, thanks for the encouragement.

It meant more to me than you know.