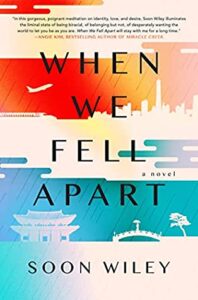

Soon Wiley’s debut novel, When We Fell Apart, is sublimely haunting and will linger in your mind long after you turn the last page. After a young woman disappears in Seoul, her ex-pat boyfriend searches for her, and in the process, for himself. Ahead of the book’s publication, Soon Wiley was kind enough to answer a few questions over email.

Molly Odintz: This is your debut, but it doesn’t feel like a debut—the writing is so sophisticated. What’s your writing process?

Soon Wiley: First off, thanks for the high praise! Like a lot of writers, my first foray into fiction was with the short story form. During my MFA program, I was incredibly fortunate to have some excellent teachers, and one practice they always preached was to give your stories time. By this, they meant that once you finished a draft of a story, it was always a good idea to put it away for a bit, a bottom desk draw was usually deemed best. And after a few months, even a year if you had the patience, they would tell you to go back and look at the story. I found this process really helpful because that self-imposed time off from a story allowed me to read as objectively as possible. It was as if I was reading a story by someone else, which helped me see where the story worked and where it was flawed. Translating this process to novel-writing was trickier, but it gave myself permission to put my novel away at various times when I was working on drafts. From start to finish, it took me about seven years to write, and there were stretches where I didn’t look at it for a few months, just so I could have fresh eyes when I started revising. The more time you can spend revising a piece of writing, the more layered and textured it’s going to become. The process certainly isn’t very efficient or ideal for meeting deadlines, but I think when it comes to writing, especially novels, time is a writer’s greatest asset.

MO: Your protagonist’s search for meaning behind his ex-girlfriend’s death becomes a search to comprehend his own bi-racial identity. Can you talk about your main character, and their journey?

SW: Min was a difficult character to write at times because he presented this paradox of sorts: how does a writer get readers to know and understand a character who doesn’t quite know themselves? As a reader, I’ve aways been drawn to characters who are lost and unsure of their place in the world. For Min, his ethnicity and nationality are certainly contributing factors to his sense of confusion, but I also think he’s of that age where most people are still trying to figure things out. From a craft perspective, I recognized early on that Min would be the perfect vehicle for the narrative. Because of his bi-racial identity, he’s able to move within certain parts of Korean culture and society, which was incredibly helpful for the plot, but because he isn’t fully Korean, he can also observe things as an outsider and act as a sort of guide for the reader. The Great Gatsby is one of my favorite novels, and I had Nick Carraway in the back of my mind quite a bit when I was writing from Min’s perspective. While Nick isn’t bi-racial, he certainly occupies a few liminal spaces. And like Nick, I think Min, while occupied with the lives of others, is really on his own journey of self-discovery.

MO: When We Fell Apart takes place at the boundaries of self-deception and truth. Characters present one side of themselves to the world and another to their loved ones. What did you want to say about the version of ourselves we present to others versus what we show to ourselves?

SW: That’s a great question! Perception, self-deception, and truth—these were all ideas that I was obsessed with while I was writing When We Fell Apart. As I was writing, I’m not sure if I knew what I wanted to say about these themes. And even when I had an inkling of what I wanted to get across to the reader, I tried to keep it somewhat vague in my head. I know that sounds a bit counterintuitive, but as a writer, you can sometimes fall into a trap where you start thinking about the themes you want to focus on in a book before you write the story itself. Once I finished the third or fourth draft, I was able to look back at what I’d written with some clarity, and that’s when I realized I was writing about characters who were practicing self-deception and bifurcating their private and public persona. I don’t want to spoil any of the plot, but ultimately, I think the book explores the real dangers of self-deception.

MO: As a follow-up question, can we ever truly know another?

SW: I tend to think, no, we can’t, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. The question of whether we can know someone was central to writing the book. Through Min’s efforts to understand why his girlfriend would take her own life, I wanted to try and answer that question.

MO: Your debut is a page-turner, but it’s also deeply literary. How did you balance between propulsion and reflection?

SW: When I set out to write When We Fell Apart, I was very aware that I wanted the book to have some sort of commercial appeal. I wasn’t sure what that really meant, but I wanted there to be real narrative momentum. The ironic part of all of this is that I’m not very well-read in the mystery or thriller genre. Like a lot of English majors, I’m fairly well-versed in what we usually think of as literary fiction, but when it comes to genre fiction, I’m woefully underread. In essence, I’d set out to write a mystery novel without every really having read what we would classify as mystery or thriller novels. At the time, I was reading Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, which happens to be one of my favorite novels. I’m a massive fan of Murakami’s work, and one thing I noticed about his writing is that he’s able to strike this wonderful balance between literary and mystery. After I noticed this, I looked back at almost all his earlier work and made a few notes about where and how he was injecting mystery elements into his narratives. This exercise led me to a more profound realization that almost all works that we classify as “classics” or “high literature” can be re-framed as mysteries or at least read as having mystery as a central component of their makeup. Take The Great Gatsby for example. The central mystery there is, who the heck is this guy, Gatsby? That question is the engine for the whole plot of the book. Another good example is The Scarlet Letter. Who is Pearl’s father? This question propels the reader for more than half the novel, and the townspeople don’t discover the truth until the very end of the novel. Toni Morrison uses a similar technique in Jazz, where within the first page the reader is asking: why did Joe Trace shoot Dorcas?

After this revelation of sorts, I saw that there was no real clear delineation between literary and genre fiction, or at least it isn’t as clear as readers and perhaps some high school teachers have made it out to be (I can say that because I am a high school English teacher). This realization was freeing, and I felt confident that I could write a plot driven novel with literary merit.

MO: Your debut is also marked by incredible emotional complexity. Where do your characters come from? Who are some of your inspirations, when it comes to character development?

SW: When it comes to my characters, I almost always start with their desires. What do they want? What are their hopes and dreams? Answering these questions helps me sketch out what type of person they might be: their social class, racial background, education, etc. While I’m answering these types of questions, I might have someone in mind, a person I know in real life, a public figure, but for the most part, I do my best characterization when I let my imagination do the work. Of course, through that process, there are aspects of myself that make their way into characters, whether it’s something they’ve experienced or a certain philosophical outlook on life, but for the most part, I like to think of my characters as people wholly independent from me. One of the more enjoyable aspects of writing is being constantly surprised by what your characters do and say.

As for inspiration, I’ve always been drawn to characters who, despite their immense flaws, the reader can’t help but pull for them. Lily Bart from The House of Mirth, Nick Carraway from The Great Gatsby, and Elena Greco from Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels, are all characters I find myself returning to again and again as a reader and writer.

MO: What’s on your nightstand/what are you reading right now?

SW: I tend to read a few books at once. At the moment, I’m reading Pachinko by Min Jin Lee and Middlemarch by George Eliot. I’ve also got Larry McMurty’s Lonesome Dove and Jess Walter’s The Cold Millions on my nightstand.

***