On April 9th 1957, at the close of a sensational 17-day criminal trial at the Old Bailey, the British newspaper proprietor Lord Beaverbrook picked up the telephone receiver to speak to one of his employees: the chief crime reporter of the Daily Express.

“Percy,” he rasped (Beaverbrook was famously not a man to waste words). “Two men were acquitted today. Adams and Hoskins.”

And then he rang off.

Nearly thirty years later, in 1984, Percy Hoskins was still so proud of that short, nine-word call from his ultimate boss and paymaster that he wrote a book about the case and called it Two Men Were Acquitted. If you are puzzled by what Beaverbrook meant, he was saying that a) the man in the dock had been cleared of murder (and therefore would not be facing the noose), while b) another man—sitting comfortably in the press gallery—was professionally vindicated, and was therefore permitted to keep his high-paid job. Evidently, in the mind of Percy Hoskins, the two outcomes were of roughly equivalent magnitude.

The case was certainly a good one for an ambitious crime reporter of the era to be involved with. Ulster-born John Bodkin Adams was a middle-aged family practitioner working in the British south-coast town of Eastbourne, where he tended to many elderly and terminally ill private patients. What initially aroused suspicion about him was that these elderly patients often listed him in their wills and then kicked the bucket after a large injection of morphine. A portly bachelor, he displayed the usual, era-appropriate arrogance of a trained physician, lived in an enormous house, and openly enjoyed the finer things of life. Among his possessions (inherited from grateful patients) was a Rolls Royce car. In 1956 he was arrested on suspicion of killing a patient six years earlier—although he was suspected of killing 162 others. At his trial he declined to take the stand, and seemed impassive throughout. His guilt was widely assumed by press and public alike. It seems to be true, in retrospect, that Percy Hoskins of the Express was the only Fleet Street commentator not to condemn Adams as guilty despite the absence of actual proof.

Two things are likely to strike any modern student of this case from sixty years ago. The first (for British people) is the strong resemblance to the more recent case of Dr Harold Shipman, a general practitioner who was found guilty in 2000 of killing fifteen of his patients at Hyde in Greater Manchester, but was suspected of dispatching over two hundred in total. But perhaps the more astonishing thing to a modern reader is that anyone ever gave two hoots about the opinions of a mere crime reporter. Isn’t it odd? Can you even name a present-day crime reporter? Yet in the 1950s, it seems that Percy Hoskins and his brethren in the national press were very big cheeses indeed. At the height of his fame and influence, Hoskins had the exclusive use of a grace-and-favour (ie free) flat on Park Lane, just for entertaining police chiefs. He liaised with Scotland Yard to produce a police insider’s book called No Hiding Place!, after which a popular TV series was later named. He appeared on TV in his own programme It’s Your Money They’re After—the title being not only a wonderful example of straightforward alarmism but also, incidentally, a masterclass in correct apostrophe use.

As it happens, the most up-to-date crime reporter I personally can name is Duncan Campbell of The Guardian (working from 1987 to 2010), so I was pleased to discover recently that he wrote the definitive history of crime reporting in Britain, entertainingly called We’ll All Be Murdered in Our Beds! (2016). The entire story of crime reporting turns out to be riveting, but of course I was drawn to the chapter on the “Sultans of the News Room” which covers figures of the same golden age as Hoskins: the splendidly-named Edgar Lustgarten, for one, and also the legendary Duncan “Tommy” Webb, whose desk at The People was supposedly shielded with bulletproof glass. This was a stupendous time to be a crime reporter, it seems. As long as you were prepared to butter up the police and hobnob with villains (and surrender all objectivity), you could cater for a mass newspaper-reading public absolutely avid for insider detail about the most sordid and violent of crimes.

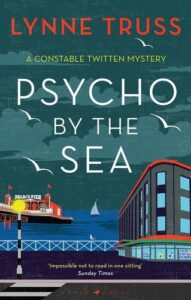

Any modern writer setting comic crime novels in the 1950s (as I am) would be mad to overlook these peacock figures from yesteryear. I have delighted in doing so. In the first of my Constable Twitten series, I brought in Harry Jupiter of the Daily Clarion, author of Heroes of the Yard and known for his vanity by-line, “The Policeman’s Friend”. He arrived in the police station saying, “I’ll need a Remington in good repair, some foolscap paper with new carbons, a large ashtray, an up-to-date street map of Brighton, a half-bottle of Bells [whisky], a green visor, some functional sleeve garters, and a place to hang my mac where I can see it.” In my latest novel, Psycho by the Sea, the terrier-like Clive Hoskisson is a very different (more moral; less self-promoting) sort of reporter, but he still carries a lot of status. At press conferences, he starts each question with, “What my readers demand to know”, as if there are two million people crowded in behind him ever urging him onwards in search of truth.

Over time I’ve collected quite a few books by Hoskins et al, and am always on the look-out for more. Aside from anything else, they are fabulous treasuries of real-life cases. Hoskins’s books come from a very long career: the first, They Almost Escaped, seems to have been published in 1938 (no publication year printed in the book); The Sound of Murder is from 1973. Both are well written and leave the reader in no doubt that a) the facts are straight and b) all the detectives mentioned were close personal friends of the author. Nowadays this latter qualification isn’t quite as reassuring as it presumably used to be. No Hiding Place! contains a wonderful section of staged photos showing the training of a young detective. My favorite part of any of his books, however, is the eye-popping glossary of criminal slang he appends to his book No Hiding Place! which includes exotic examples such as:

It was a dead tumble. They realised what was happening.

Moon. One month’s imprisonment.

On the cross. Obtaining a livelihood by dishonest methods.

Coring mush. Fighting man.

I like to imagine that Hoskins was supplied with this jargon by an underworld informant who was at the double-double (untrustworthy), who saw him as a steamer (a mug or stupid fellow).

However, I suppose what mostly intrigues me about news writers from this era is their adamantine air of certainty. If Hoskins tells his readers that underworld operatives call a five pound note a “pangy bar”, he states it as truth. Relativism does not exist. In the process of a police investigation, a piece of evidence pins guilt on the accused and he is duly convicted, sent down and hanged. The role of the popular reporter in this is never agonized over; no case of a hanged man (or woman) is reconsidered after the event. In The Sound of Murder, Hoskins goes so far as to address one of the clearest cases of a miscarriage of justice: when Timothy Evans was hanged in 1950 for the crimes subsequently attributed to his serial killer neighbor John Christie. By the time Hoskins wrote The Sound of Murder in 1973 an official inquiry had granted Evans an unequivocal posthumous pardon, yet Hoskins still maintains that the system got it right.

I have seen many murderers in the dock and my feelings for all of them are much the same. By their act they put themselves beyond the pale and it matters not one jot or tittle to me that they may have killed for passion or greed. Any sympathies I have are for the devoted, poorly paid detective who overcomes every difficulty and brings the criminal to book.

Back with Dr Bodkin Adams in Eastbourne, a quick look at Wikipedia will tell us more about the man – and the case – than the whole of Hoskins’s book. There is dark talk of Adams being involved sexually with the Mayor of Eastbourne, and of him being known by everyone as a shameless sponger, with a habit of treating other people’s property as his own. And he was certainly dishonest. Evidently after the death of the woman he was accused of murdering, he billed the estate for over a thousand medical visits, when in fact he’d seen her more like 300 times. Since Hoskins’s own book on Adams, there have been half a dozen more examining “Eastbourne’s Doctor Death”. Interestingly, Eric Ambler included Adams in a 1963 book, The Ability to Kill, but the chapter was removed before publication, due to fears of libel. How I would like to see what he wrote!

All of this makes me wonder what persuaded Hoskins, in his old age, to publish on the Adams case. Could a smidgen of regret be behind it? Did he perhaps look back on a career spent unequivocally promoting the stolid virtues of the police – and indeed championing the entire criminal justice system—and decide to highlight the single example of a time when he thought the police had bungled the job? Look, he says; I did once stand up for the falsely accused! But in retrospect, what a dreadful choice he made by pinning his colors to the mast of John Bodkin Adams’s innocence. Two men were definitely acquitted on that day in April 1957. But were either of them totally innocent?

***