Philip Agee remains unique in the annals of US intelligence in that he went from being the consummate intelligence insider—nobody is more entrenched than a Central Intelligence Agency case officer in the field—to being a thoroughgoing outsider, and did so by choice. Agee has continued to be, with the exception of Aldrich Ames, the United States’ most hated erstwhile spy. Within the CIA, his “was taken as one of the most harmful, worst betrayals that we [have] suffered, and the hostility to him was greater than it was towards almost anybody else,” notes Glenn Carle, himself a CIA whistleblower with respect to “enhanced interrogation.” While Agee did assert the natural right of purportedly noble individuals to speak truth to power against the agency’s cult of secrecy and insularity, what really set him apart from other angry spies was the way in which history in the making—the full sweep of contemporaneous events—wormed its way into his head and helped motivate and consolidate his turn, however he might later be judged.

When Agee left the CIA in 1969, it was still a relatively young organization, having been officially created by the National Security Act of 1947. But it was built on the rather unsteady foundations of the wartime Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—which had been, despite the legendary status it inspired then and continues to enjoy owing to the charitableness of nostalgia, an erratic seat-of-the-pants enterprise. The Cold War, of course, created a crucial demand for intelligence, prompted exponential growth in the CIA’s personnel strength and budget, and afforded the agency immense traction and clout within the United States’ national security bureaucracy. Furthermore, during the Eisenhower administration CIA Director Allen Dulles—fully supported by his older brother, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles—burnished its reputation with covert action that secured US-friendly regimes in Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), and the Congo (January 1961). Yet the agency had performed poorly in the Korean War and embarrassed itself with the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in April 1961. Rightly or wrongly, in the mid- to late 1960s its intelligence assessments were partially blamed for the United States’ ongoing frustrations in Vietnam. By the early 1970s, the CIA was an underconfident institution, worried about its place in an open democracy and less sanguine than it appeared about the stalwartness of its second generation of officers.

In fact, a fair number of intelligence officers who were Agee’s rough contemporaries were experiencing disillusionment. Some, of course, were imperturbable cold warriors for whom the twinned ends of planting capitalist democracy and extirpating Marxist-Leninist communism justified any effective means. Others took a more nuanced view, subscribing to the American mission in general. Conceding that US institutions—including the CIA—made mistakes that ranged from mere operational errors to major strategic ones, they resolved to remain part of the system for lack of any better alternative. For them, becoming malcontents or whistleblowers or, beyond that, traitors, were not viable options; they had careers as professional patriots that they were not about to upend. Recrimination and reconsideration might someday be warranted, but not while they were busy doing what had to be done for themselves as well as their country. Then there were irrepressibly disaffected intelligence officers. What they had seen in the world of shadows they had chosen to inhabit had intolerably unsettling psychological effects. Some simply opted out of the intelligence business, leaving behind what they perceived as a somehow wrongheaded or just bad life, choosing never to talk about it or address it further. They might have had particular experiences that were disillusioning and upsetting, such as recruiting an agent who wound up dead. Or they might have developed a broader philosophical sense that convincing vulnerable, needy people to commit treason—the meat and drink of spycraft—was either immoral or, in the martial countries that were the focus of the agency’s attention, futile. Among officers leaving the CIA before retirement age, this variety was perhaps the most common. Very few felt compelled to do something about the putative iniquity of American spying. As David Corn has observed, “It’s very rare that someone decides to confront that institution, expose what they think is wrong about it, and bring it to a halt.”

Agee was just that rare. His turn shocked and traumatized the CIA, which characterized him as its first defector. Its institutional loathing of Agee, and its wariness of his story as precedent, have endured. To this day the CIA is sensitive to the public disclosure of information about Agee’s activities. The Philip Agee Papers—the various and sundry documents that he accumulated between the time of his resignation from the CIA and his death in January 2008, central to the composition of this book—have been held at New York University’s Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives since 2009, when his wife Giselle Roberge Agee donated them to the library. The papers were in his Havana apartment when he died in January 2008, and Michael Nash, then the Tamiment Library/ Wagner Archives’ associate curator, supervised their transport from Cuba to the United States. Owing to US restrictions on direct flights between the two countries, he arranged for the documents to be flown to Montreal and then transferred to New York. Unsurprisingly, the CIA and other government agencies got wind of these arrangements. CIA, FBI, and other national security officials had the Montreal-to-New-York flight grounded in Cincinnati, where they seized the papers, combed through all of them, and confiscated an appreciable number of documents before allowing the shipment to proceed to New York. They also appeared to tear out and retain a significant number of pages from Agee’s datebooks from several years—especially in the 1990s and 2000s, when Agee was spending much of his time in Cuba—and to confiscate his 1980, 1989, 2002, 2003, and 2005 datebooks in their entirety.*

Agee was certainly the only publicly disaffected American intelligence officer to confront the CIA on full- fledged ideological grounds and to oppose American strategy and foreign policy on a wholesale basis. He left the agency after twelve years as a case officer in Latin America, at least in part over his disenchantment with what he perceived as the CIA’s undermining of liberal democracy to serve American economic and political interests. He later resolved to subvert that effort by writing a book—entitled Inside the Company: CIA Diary—setting forth his political and philosophical grievances, published first in the United Kingdom in 1975 and about eighteen months later in the United States. It would take him five years to write and would become the urtext of spy tell-all books. Unlike most other vocally unhappy CIA officers, he also declined to submit the book to the CIA for vetting and redaction, violating his agency employment agreement. Unlike any other such officers, he published the names of some 400 clandestine CIA officers, agents, and fronts. (A CIA “officer” is a US government civil servant employed by the agency. A CIA “agent” is an outside party clandestinely recruited by the CIA to advance CIA objectives.)

Published in 1975—the so-called Year of Intelligence—Inside the Company scandalized the agency, enraged its top management as well as its rank and file, and compromised its operations in the Western Hemisphere. The book and Agee’s campaign to expose intelligence operatives and operations drew bipartisan opprobrium among American politicians—Barry Goldwater wanted Agee’s citizenship revoked, and Joe Biden said he should go to jail. For the rest of his life, Agee would continue, albeit with diminishing returns, his efforts to undermine CIA covert operations and other aspects of what he considered objectionable US policies.

There have been quite a few former intelligence officers who have turned against the CIA or some other federal intelligence agency. But Agee set himself apart from other government dissidents. Perhaps the most prominent one of that period was Daniel Ellsberg, who in 1971 published the Pentagon Papers—a classified study of the Vietnam War that revealed, among other things, the Johnson administration’s undisclosed expansion of the war in spite of growing evidence of its military futility. In a 2016 piece in the New Yorker, Malcolm Gladwell drew a perceptive distinction between Ellsberg and Edward Snowden, who in 2013 exposed the breadth and depth of the National Security Agency’s digital surveillance capabilities and practices. Gladwell pointed out that Ellsberg really remained a dedicated security professional—an insider who exposed secrets to show that the US government was ill-serving its own agenda and to spur remedial action.

At least at the time he leaked the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg was a whistleblower in the true and original sense: a conscientious patriot and dedicated institutionalist addressing a transgression in the government’s execution of policy by using the only effective recourse—namely, public exposure—that he could discern. He and those like him stayed inside the envelope of the loyal opposition, if sometimes only barely. Some combination of the cumulative value of well-intentioned and narrowly targeted disclosures like Ellsberg’s and the cumulative damage of broadly destructive ones like Agee’s impelled Congress to pass the Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989, which, as amended, in effect expanded the lane for insiders to lodge complaints about legally or ethically questionable policy implementation by protecting those who stayed in that lane. This statutory scheme has encouraged legitimate whistleblowing complaints of significant consequence in American affairs of state—notably, in 2019, that of a CIA officer alarmed by President Donald Trump’s apparent withholding of foreign assistance to Ukraine for his personal political gain, which led to Trump’s impeachment.

The label “whistleblower” aptly applies to, say, William Binney, a former National Security Agency (NSA) intelligence officer who registered concerns about its surveillance program through designated channels. It does not comfortably describe Snowden, who by contrast was essentially a young contractor with digital aptitude who saw the World Wide Web in idealistic terms. He had no deep fealty to the US intelligence and security apparatus, and in his exposure acted as an interloper looking to compromise rather than cure it. In a generally meticulous, peer-reviewed 2019 article, Kaeten Mistry casts Agee merely as the primus inter pares whistleblower and “insider dissident” among other “anti-imperial” intelligence officers, one who both nourished and was nourished by a substantial if informal transnational support network. The network and the synergy existed, but the term “whistleblower” is certainly too tame to apply to Agee, and the label “anti-imperial” too bold to describe the additional disaffected government employees—including Ellsberg, Frank Snepp, and John Stockwell—whom Mistry mentions. While there was no statute protecting whistleblowers in Agee’s day, even if there had been it wouldn’t have been a sufficient outlet for him. His grievances were wholesale, involving the CIA’s entire raison d’être and the American project writ large. He was part of the opposition, but he was no longer loyal. Calling Agee a whistleblower thus seems to constitute at least a modest category mistake—a venial sin of overinclusion. (He is also not a mere “leaker.” Indeed, one recent book on that subject does not even mention him, leaping from Ellsberg to Snowden.) Agee was in some ways less of an outsider than Snowden, but in paramount respects more of one. While he was a career intelligence officer who had some appreciation going in that he would have to get his hands dirty, he crucially differed from Snowden in that he did not see the governance problem he had uncovered as a narrow one that could be fixed by self-restraint at the margins; Agee objected to the American Project writ large.

Over the CIA’s history, numerous spies have aired their complaints publicly, but Agee was among the first. Most, like Ellsberg, have harbored grievances about the execution of a particular program or institutional culture with an eye to fixing a generally defensible system. Victor Marchetti, once a very senior agency analyst, re-signed in 1969—shortly after Agee did—and published his book, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence, a year before Agee published Inside the Company. Marchetti impugned the agency’s overall effectiveness and its arrogation of covert control; he was for a while somewhat sympathetic with Agee, but he acknowledged the need for a reoriented CIA. Former CIA analyst Frank Snepp thought the Americans withdrew from South Vietnam too shambolically in 1975, selling out Vietnamese locals who had helped them, but he chafes at suggestions that he and Agee are remotely equivalent. John Stockwell, another ex– case officer, illuminated the counterproductive nature of CIA support for military operations in “secret wars,” but he didn’t dump on the entire American enterprise even though he became a friend of Agee.

>More recent critics from within have had even narrower, smaller-bore grievances and less time for Agee. For instance, Glenn Carle, a senior CIA case officer, resigned and chronicled the inefficacy, cruelty, and immorality of the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation”—that is, torture—program for al-Qaeda suspects. He considers someone like Stockwell a mere “malcontent” with some legitimate complaints, himself a pro-American idealist, Agee (or Snowden) a near-sociopathic traitor. “I oppose torture. I strongly support the mission of, and most of the officers in, the Agency. However many errors the United States makes in policy choices and operational acts, that doesn’t in any way affect my loyalty to and support for the overall mission of the CIA in U.S. foreign policy.” He and most other disaffected ex-CIA officers have not undergone sweeping ideological conversions.

Agee raised the alarm not about a particular practice or policy but rather about the CIA’s to him dubious role as an undemocratic enforcer of a democratic nation’s interests. He is the only former case officer to systematically expose the identities of intelligence officers and assets to the public, damaging their careers and theoretically jeopardizing their lives. But he is more complicated than a mere villain. He is a figure of profound ambivalence and considerable subtlety, and a more sympathetic character than the likes of the mercenary, soulless Ames, though that is an admittedly low bar. Since November 2016, Agee has become a more resonant and ominous figure. American politics and government have arguably reached their lowest point: lower than the escalating Vietnam years of a Johnson administration that at least spawned sixties idealism, lower than the apocryphal “malaise” of the Jimmy Carter years, even lower than the post-9/11 paranoia, grandiosity, and ineptitude of George W. Bush’s presidency. The election of a true American abomination—especially one intent on gutting the legacy of a largely admirable predecessor—presents many Americans with a country of which it is hard to be proud. And it makes salient the question of what national and international circumstances might prompt a person—particularly one whose very profession is applied patriotism—to turn against his or her government. The one epoch in the past seventy-five years almost as bleak as the tenure of Donald Trump was the sordidly deflating post-Watergate period, when Agee decided to expose CIA officers and agents. It was a veritable golden age of intelligence officer disaffection, yielding Snepp, Stockwell, and others.

Certainly another Agee could emerge. Agee and those of his vintage walked what Graham Greene famously called “the giddy line midway.” Greene appropriated the notion from Robert Browning’s long poem “Bishop Blougram’s Apology.” The relevant lines are these:

Our interest’s on the dangerous edge of things

The honest thief, the tender murderer,

The superstitious atheist, demirep

That loves and saves her soul in new French books–

We watch while these in equilibrium keep

The giddy line midway.Article continues after advertisement

In contemporary American vernacular, “giddy” suggests giggly or overeager, but Browning—and Greene—understood the word to mean, in its Victorian sense, vertiginous. Greene applied this part of the poem, which he called “an epigraph for all the novels I have written,” particularly to spies, including the legendary MI6 mole Kim Philby, with whom he remained ambivalently sympathetic. Greene considered disloyalty quite human, and therefore forgivable. Novelist and journalist Lawrence Osborne has commented that holding “the giddy line midway”—that is, wavering between duty and transgression—describes many of Greene’s protagonists and encapsulates “the enigma of betrayal” that so fascinated him. It also describes Philip Agee pretty well. For at least three years, he harbored doubts about the agency’s agenda, contemplated abandoning it, yet dutifully prosecuted its mission; then he liberated himself along an almost equally unstable tangent until, at length, he became a dedicated dissident and an agitator for life.

___________________________________

*The US agencies indicated in writing the number of documents they had removed but did not specifically identify them. New York University initiated a lawsuit to have the documents released but eventually dropped it. To the extent that Agee himself wished to eliminate documentary evidence of post-CIA activities inconsistent with his public representations, he might have culled his own files accordingly. The documents Agee obtained via his Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request in the 1970s, which the US agencies left in place, remain the most probative primary materials on the relationship between Agee and the CIA. Where cited, I specify their location in the Agee Papers and indicate that they were obtained by FOIA request. Many of those documents have been declassified and are available on the CIA’s website. I submitted wide-ranging FOIA requests regarding Agee to the CIA, the FBI, and the Department of State in 2010 and 2015. Although the agencies provided little that Agee had not obtained himself or which they had not already declassified and made publicly available, the FBI did furnish several newly disclosed documents that shed some light on its investigations of Agee; these are duly cited, mostly in chapter 7. The other agencies also provided a few scattered documents of interest, also cited. Since this book focuses on Agee’s point of view, I have relied on secondary sources to account for the attitudes of other well- known figures rather than consulting any available collections of their papers or the like. Among the people who knew Agee well and were still alive as I was researching this book, his second wife, Giselle Roberge Agee, was fully co-operative. His first wife, Janet, passed away in 2006. Philip Agee Jr. was initially inclined to cooperate in my research for this book but backed away after a substantive exchange of e-mails and one meeting, perhaps concerned that the book might question Agee’s motives and national loyalty. Christopher, Agee’s youngest son, did not respond to my inquiries. Several of Agee’s classmates from Jesuit High School in Tampa and from Notre Dame were forthcoming, as were Melvin Wulf, his longtime lawyer; Lynne Bernabei, the attorney who represented him in his libel action against Barbara Bush; and Michael Opperskalski, a left-wing journalist based in Cologne whom Agee befriended in the 1980s when he lived in West Germany. Others in his life who may have still been with us as I composed the book I was unable to find.

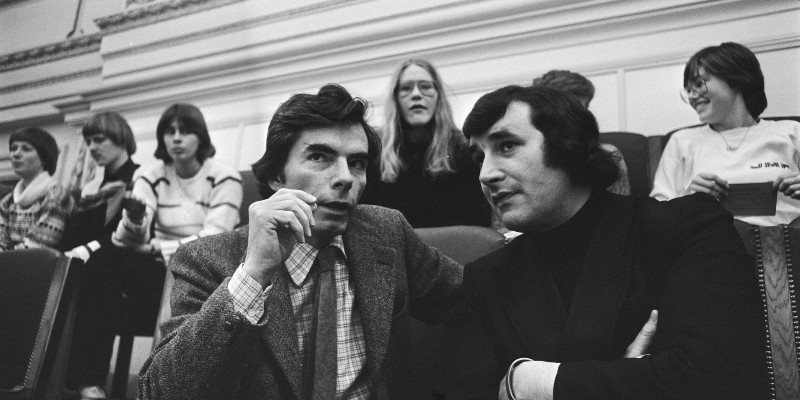

—Featured image: Agee in 1978

Collectie / Archief : Fotocollectie Anefo

Bert Verhoeff / Anefo