I think it’s safe to say that becoming an expert in Shakespeare’s plays presents difficulties. What would “expertise” entail? Do you need to know every consistency and inconsistency in all the versions of every play cobbled together in the First Folios (pluralized because all the extant versions are also slightly different)? What about wordplay rooted in local pronunciation of the era, which sounded a little like current English in areas of Ireland or England’s West Country? Should you know the etymology of every single word—if Shakespeare didn’t allegedly coin it—and everything that word alluded to at the historical moment in which each play was written, a date that’s nearly always disputed? Do you need to know the pop culture references of the day, since Shakespeare’s plays were the era’s equivalent to R-rated TV?

Expertise is evasive, but not for lack of trying. By the sixth line in an 1866 New Variorum edition of Othello, the commentators are waging a footnote battle with a word count threatening to eclipse the play’s. The multiple Oxford, Arden, or Cambridge editions never agree with each other about a stage direction’s “authenticity.” Then there’s Harold Bloom’s old-guard-turned-hot takes, Steven Pinker’s framing of Shakespeare as a psychologist, and a book worth reading, Marjorie Garber’s Shakespeare After All (enlightening, comprehensive, and readable).

All this is to say: I’m not an expert on Shakespeare. I’m a fan of reading the plays, not watching or hearing them, a statement most Shakespeare experts deem profane. So be it. The only Hamlet I’ve liked was Iain Glen in the movie adaptation of Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guidenstern Are Dead. The performances I’ve seen do what Hamlet explicitly tells actors not to: scream like town-criers, stressing all the wrong words and winking to signal puns. “That moment was metafictional—he was being sarcastic!” experts will protest. Probably, maybe, but the plays in my head took his advice.

Despite lack of expertise, I was (once, in a pinch) tasked with teaching a college course on Shakespeare. I picked some plays and tried to read everything ever written about them. I didn’t, because that would’ve been impossible even if those plays were the only thing I taught that semester, and I had three other unrelated classes. I shelved the book I was writing, which was accustomed to neglect by then, and it was just as well. I was stuck on what one character should’ve been doing. I spent those months working and reading ninety hours a week, and when the semester hit Othello, I had either a breakthrough with my shiftless character or a breakdown over netting less than $4.00 an hour. I don’t know which Samuel to blame the break on, Johnson or Coleridge, but let’s go with the latter.

Before we get to Sam, if you’ve never read Othello, here’s a synopsis with spoilers: prior to the opening of the play, a soldier named Iago was poised to become lieutenant to a general, Othello. Instead, Othello made Iago ensign (a flag-bearer and confidante) and chose Michael Cassio for lieutenant (the next in command). Cassio has higher social rank than Iago and more book-smarts than experience in the field. To make matters stickier, there were rumors Othello slept with Iago’s wife, Emilia, while Iago was off fighting a war. When the play opens, we learn Othello has now eloped with a young woman, Desdemona. As it happens (wink), Iago has promised to hook a gentleman named Roderigo up with Desdemona, bilking Roderigo out of cash and jewels in exchange. After not being named lieutenant, Iago turns his manipulative skills and new role as confidante on, well, everyone. By the end, all but Iago, Cassio, and a few side characters (including a clown, obviously) will be dead. Cassio unwittingly kills Roderigo. Othello, convinced Desdemona is sleeping with Cassio, kills her. When Emilia realizes what Iago has done and relays his shenanigans to those left standing, he kills her. Iago, who has provoked all this destruction by pouring “pestilence” into everyone’s ears—preying on their fears, insecurities, and passions and telling them what he knows they’re prone to believe—says, “From this time forth I never will speak word.” And, finally, Othello sees he’s killed his love for no reason and kills himself.

The play finds Shakespeare obsessed with several topics that thread throughout his larger body of work. Characters mirror each other, examining arbitrary ways in which societies assign power based on class, gender, race, age, religion, occupation, title, and anything else Shakespeare can think of. He tries to tease out how much freewill we have from what might be a delusional façade, often suggesting we act organically according to who we are, an identity we have little control over. Other frequent fixations saturate the text, too, namely our worthless attachment to reputation and several lines from the Book of Matthew (one of them says people should make no vows, and the other asserts, probably correctly, that using any words beyond “yes” and “no” never works out well).

Nearly all of this flew highly and swiftly over the head of poet and literary critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose literary legacy is replete with many stupid, terrible things. Among these are one ancient mariner and some intensely racist opinions about the character Othello—opinions that required willfully ignoring a whole lotta words that show Coleridge’s specific variety of racism had been frowned upon more than two hundred years before he could put his stupid pen to his stupid paper.

But one of the most oddly off-putting bits he wrote dealt with Iago. The still-echoing commentary was written at the end of the first act, and, because Iago offers readers plenty of reasons to dislike himself, the moment seems like one of Coleridge’s lesser stupidities—something almost benign: “The last speech—the motive-hunting of motiveless malignancy—how awful!”

“The motive-hunting of motiveless malignancy.”

Mining critical anthologies, one will again and again see Iago’s motives called “inscrutable” or simply “insufficient.” Some scholars say he was a symbolic character echoing earlier morality plays, which seems well-researched but is no less incomplete. Others offer competing medical diagnoses of Iago: sociopathy, psychopathy, narcissistic personality disorder. Many take an easier way out, claiming readers aren’t supposed to know what propelled Iago. Some assert modern readers have become too comfortable with the notion of moral relativity to know evil when they see it. Marjorie Garber offers several of these theories and more because Garber is professional and analytical and measured.

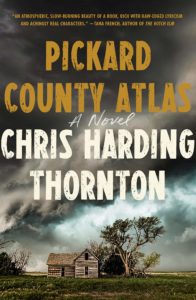

I am not. That is why, when I read these sentiments on Othello, a dam in my head broke and I resolved: the shiftless character in the book I’d shelved must become Iago, a marionettist who pours poison in ears. That’s right—I was so irate, I would attempt to redeem—even avenge—one of the most problematic and contemptible characters in English literature.

I was so irate, I would attempt to redeem—even avenge—one of the most problematic and contemptible characters in English literature.Since this has already turned into a New Variorum footnote, I’ll limit my analysis of Iago’s motives to one line. It’s on the first page of the edition I’m looking at.

Angry at not being promoted to lieutenant, Iago says, “I know my price, I am worth no worse a place.” Iago knows his price—his value—in the world. He doesn’t say he’s worth better, or more—simply “no worse.” Not better, not worse. Compare Iago’s value to the wealthy gentleman he’s speaking with. Compare it to the gifted and eloquent general he’s speaking of. Compare it to the educated and well-connected but inexperienced man who’s been promoted to a position the man didn’t need. The same position could’ve meant a major change in Iago’s life, which has been brutal. As ensign, he might be better armored, but he is what he’s always been: a soldier who has “seen the proof / At Rhodes, at Cyprus, and on other grounds.” He has killed. He has watched men die—men he knows, men he’s slept beside, and men who have been strangers to him. He’s seen and committed all this on behalf of some senators, on behalf of a place where he’s considered honorable but no less expendable.

Iago knows his value. He’s seen it in bloody, unrecognizable mounds in a field. And now he’s had a glimpse at becoming a lieutenant, a position with more control than he’s ever had. That’s gone now. Here on the first page. Better armored or not, without that, Iago will be what he’s always been, an honorable tool used to advance a nation’s prosperity and control. A nation that has not paid him back.

Iago does know his worth in that grand scheme. It is nil.

And what do people who are exceptionally angry about their lack of value in a society very often do? They take down anyone who may be more vulnerable. Because those are the people who are within their reach. That’s what’s within their control. The senators, on the other hand, are far off in their chambers.

If you’re curious about whether or not I redeemed Iago, no, I didn’t. I couldn’t resist making him more human.

***