Across the transatlantic world in the early decades of the twentieth century a terrible wave of poison attacks took place, cruelly claiming hordes of human victims. In contrast with the toxic chlorine, phosgene and mustard gases which armies put to such ghastly and inhuman use during the First World War, however, these particular poisons were not delivered via canisters and shells. Rather, the instrument through which these poisons inflicted their damage was the pen—the so-called “poison pen” (a term which encompassed as well that click-clacking symbol of modern business efficiency, the typewriter). For these poisons were words—words which, like weapons of war, could not only hurt but in some cases kill.

Hostilities seem to have commenced in the American state of New Jersey. There in 1909 at the city of Elizabeth, located near New York City, a sneaking individual possessed of a “serpent typewriter,” as the newspapers put it, launched a campaign of hurtful verbal harassment against some of the city’s “best people” with a series of anonymous letters, “some innocuous, some catlike, some downright indecent.” One of the letters that was made public hatefully accused a respectable Elizabeth matron of clandestinely prostituting herself to men in New York:

She keeps one or two roomers and does a little dressmaking to hide her double life. Look at her clothes of elegance. Yet her husband is a baggage checker on the P. R. R. [Pennsylvania Railroad] in Winter and purser on an Albany [Hudson River ferry] boat in Summer, never saw $80 a month in his life. Yet they keep a maid and she is on the go all the time. Once a week she meets an Elizabeth man over on Staten Island and once a week she meets a N. Y. man in N. Y. C., and in that way she makes $40 a month. She will do anything but honest work for money.

The chief victim of this manic postal onslaught was another woman, Mrs. Florence Jones, wife of dentist Charles F. Jones, treasurer of the New Jersey State Dental Society, who lived on fashionable Madison Avenue. Not only did Mrs. Jones receive objectionable letters, the Jones household additionally was inundated with “free literature” on obesity, insanity, alcoholism and drug addiction, all of which information had been requested by notes with Mrs. Jones’s name and address attached to them. Shockingly in March 1914, it was the Jones’ next door neighbor, Mrs. Anna Pollard, the forty-three year old daughter of William Henry Harrison Dunn, wife of New Jersey Public Service Commission electrical engineer Nelson Pollard and mother of two daughters, who was arrested and charged with all this malicious activity. The highly esteemed Mrs. Pollard was nothing less than the president of the Elizabeth Ladies’ Aid Society and a member of Christ Episcopal Church and the Boudinot chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR).

At her trial Mrs. Pollard appeared with her face entirely swathed in a mummifying veil and Reverend Edward Lyttle, minister at Christ Episcopal Church, sitting beside her. The back-and-forth bickering between prosecutor Alfred A. Stein and Samuel Schleimer, counsel for the defense, grew so heated that the presiding judge broke his gavel in furiously silencing the squabbling attorneys. Under grueling examination and cross examination lasting for over ten hours, famed handwriting expert William Kinsley testified that the same machine which had produced the type on letters Mrs. Pollard had indisputably typed with her personal typewriter had done so as well with the poison pen letters. Type, he explained, could be, like handwriting, individually identified. In this case, imperfections in the letters “h,” “e,” “i,” “o,” and “u,” were identical in all the documents. The defense countered with testimony from Mrs. Pollard’s maid that many townswomen had dropped in at the Pollard house to use Mrs. Pollard’s typewriter, including Mrs. Jones’ estranged sister-in-law, whom the defense tried vigorously to implicate in the crime. The jury, whether genuinely perplexed over all the typewriter testimony or simply unwilling to accept that a woman of such standing as Mrs. Pollard could do such things, voted to acquit.

As soon as Mrs. Pollard went free, the sending of poison pen letters recommenced, this time not in type but in the form of hand printed block letters and words cut and pasted from newspapers. (Once bitten, twice shy?) The unfortunate Mrs. Jones again stood at the head of the recipients. In October Mrs. Pollard, having fallen into a wily trap laid for her by the local Federal postal inspector, was again arrested and charged with the crime; and this time she confessed to having written the letters, her motivation for doing so evidently having been her keen social jealousy. (She desperately wanted to “keep up with the Joneses,” as it were.) At her sentencing a sobbing Mrs. Pollard was let off lightly by the merciful judge, who declined to give the Elizabeth matron any jail time and fined her only $200 (about $5000 today); but the disgraced woman was expelled from the Boudinot chapter of the DAR after her conviction, which some may have felt was sufficient humiliation to someone as painfully conscious of social standing as Mrs. Pollard. She died in 1947, still residing at the same house in Elizabeth with her two unmarried daughters, one of whom ironically had become a dentist.

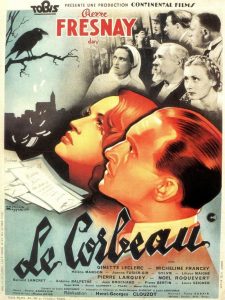

This vein of epistolary venom, once opened, proved impossible for Lady Justice to stanch. A few years after the contentious affair at Elizabeth, in 1917, someone across the Atlantic Ocean began inundating the small French provincial city of Tulle with malevolent screeds, which were left at mailboxes, doorsteps and windowsills, slipped into women’s shopping baskets and even placed on church pews and in confessionals. In December 1922, Angele Laval, the thirty-seven year old daughter of a comfortably circumstanced shoemaker’s widow, was arrested for writing the letters and charged with defamation. Although Angele denied guilt, she was convicted, fined and sentenced to a term of penal servitude. Several suicides had resulted from the letters, including that of Angele’s own mother, who had been mortified by the accusations against her daughter. After her release from prison, Angele lived reclusively in Tulle until her death in 1967. French director Henri-Georges Cluzot’s classic 1942 mystery film Le Corbeau (The Crow) was inspired by the dreadful events at Tulle.

1922 and 1923 proved banner years for poison pen cases in the transatlantic world. In May of the latter year, the internationally prominent George Maxwell, an expatriate Englishman who was co-founder and current president of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), was indicted in New York for “sending scurrilous and obscene letters through the mail.” The indictment claimed that over the course of a decade the handsome fifty-two year old Maxwell, styled a “gay Lothario” (i.e., serial womanizer) by newspapers, had mailed, with tragic consequences, nearly one hundred and fifty poison pen letters sexually defaming nine prominent East Coast socialites (Possibly there were as many as forty women involved.) It was said that as a result of the letters homes had been broken up, a man had gassed himself, a woman had swallowed iodine and another woman had been driven insane.

Maxwell’s chief accuser was Manhattan stockbroker and aviator Allen R. Ryan, whom New York City Police Commissioner Richard E. Enright had appointed Special Deputy Commissioner for National Defense upon American entry into the Great War. Ryan, a recipient of one of the infamous letters, publicly accused Maxwell of having had an affair with his wife, oil heiress Sarah Tuck Ryan. Claiming that he was the victim of a high level conspiracy, Maxwell immediately sailed back to the United States from England to contest the charges, which a judge dismissed in July, having found there was no evidence that Maxwell actually authored the malicious missives. Seemingly vindicated, Maxwell continued to serve as president of ASCAP until 1941.

Around the time that terror stalked Tulle and a great wave of spleen engulfed high society in the northeastern United States, a rash of spiteful and often coarse anonymous letters—some of them melodramatically signed “by the unknown hand”—began appearing across the pleasant and seemingly placid little seaside town of Sheringham in Norfolk, England. After five months of finger-pointing and recriminations, police in November 1923 arrested twenty-five year old Dorothy Myrtle Thurburn, daughter of artist Percy Cecil Thurburn and great-granddaughter of Roger Thurburn, who in the early Victorian era had been Her Britannic Majesty’s Consul in Egypt. A former Girl Guides leader who had arrived in Sheringham with her mother in 1921 and received scores of poison pen letters herself, Dorothy was described in newspapers, appreciative of the seeming incongruity between her appearance and her alleged wrongdoing, as a “pretty, demure little miss, very girlish in her appearance.” Dorothy categorically denied having written the anonymous letters, although she, an artist’s daughter, admitted to having drawn caricatures of as well as made frank written comments about Sheringham residents.

The letters which Dorothy denied writing, some of the less explicit of which were read out in court, were anything but demure. In sometimes shockingly profane language they accused Sheringham citizens of everything from having had extra-marital affairs and out-of-wedlock children to being “badly made-up,” “walking like a duck” and having “yellow-dyed hair” and “odd hips and twitching eyes.” The brazen letter writer, who seemingly lacked any sense of self-awareness, denounced local women as jealous old cats and she-devils. Her targets included even the local gentry, as embodied in Lady Brainbridge of nearby Haddon Lodge.

Dorothy Thurburn’s trial saga dragged out into 1925, as stymied juries twice proved unable to reach verdicts. At the first trial the prosecution argued that Dorothy had left vicious letters to herself in order to avert suspicion and a police constable testified that he had actually witnessed the “demure little miss” posting correspondence at a pillar box in which poison pen letters were shortly afterward found. Dorothy’s defense attorney declared that her caricatures had all been done in good fun and that she had sincerely apologized afterwards to anyone whom she might have been offended. He also argued that the drawing ink used to compose the anonymous letters was readily obtainable at ordinary stationers’ shops and that during the time they had been sent, Dorothy had innocently kept a mild diary which gave no inkling, if you will, of any wicked activities.

The defense additionally offered as a character witness famed novelist Henry De Vere Stacpoole, author of the critically derided but bestselling (and later several times filmed) novel The Blue Lagoon (1908), giving rise to this amusing courtroom exchange between the judge and Dorothy’s attorney:

Judge: “You have written ‘The Blue Lagoon’?”

Witness (smiling): “Yes.”

Mr. Cassels: ”My Lord, he is not charged with that.” (Laughter).

At the second trial, Dorothy’s new attorney was Edward Marshall Hall, England’s so-called “Great Defender,” whose gallery of notorious clients included George Joseph Smith, the infamous Brides-in-the-Bath murderer. (He had also been briefed to defend accused wife slayer Hawley Harvey Crippen, but the two men fell out with each other.) The Great Defender made considerable headway in discrediting the police constable’s claim that he had seen Dorothy posting letters in the telltale pillar box. In summing up, however, Mr. Justice Sankey suggestively asked of letters which Dorothy had admitted to writing, “They are very funny letters for a young lady to write. Do you not think you are dealing with rather a peculiar lady who writes letters of that character? You may put it rather higher. Do you not think you are dealing with an abnormal young lady?” A torn jury again deadlocked.

At Dorothy’s third trial in early 1925, the prosecution declined to offer evidence and Sheringham’s “demure little miss” at long last walked free in fact, if not free from suspicion. Dorothy and her mother, who always stood by her, left the county, Dorothy proclaiming, “I never wish to see Norfolk again as long as I live.” Shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, Dorothy lived alone on private means, still beside the seaside, in Eastbourne, Sussex, where she passed away, unmarried, in 1975, a half century after she had been acquitted of crime. Whether or not she really was the “unknown hand” who callously engineered one of the most paradigmatic of real life English poison pen mysteries still remains, well, unknown.

Nasty poison pen outbreaks continued to occur throughout the Twenties and into the Thirties, with no one knowing where the contagion would strike next.Nasty poison pen outbreaks continued to occur throughout the Twenties and into the Thirties, with no one knowing where the contagion would strike next. In 1929 Frenchwoman Martha Gitton was sentenced to three months in prison and ordered to pay 15,000 francs in damages after she was convicted of inundating the provincial town of Gien with anonymous letters filled with wildly scurrilous passages. The case was considered an especially shocking one because Martha had appeared to all to have been a keenly religiously devout young woman. Indeed she was regarded locally as “almost saintly,” in the words of the newspapers, attending church daily, helping the pastor in his work and succoring myriad benevolent projects. Worse yet, Martha not only had spent her nights drafting poison pen letters, she had, after attending a pilgrimage at Lourdes, faked a miraculous cure from tuberculosis, for which she had derived much regional fame.

Five years later (in November 1934), when Reverend John William Shaw, Archbishop of New Orleans, suddenly died from massive heart attack, friends said the fatal event had been brought on, in part, by the Archbishop’s agitation over a series of poison pen letters which had recently been mailed all over the city, wherein were contained “vicious charges against him and some of his priests.” The press left the nature of these charges tantalizingly unexplained and in three weeks the affair was overshadowed by another reported outbreak of poison pen letters, this time in Vermilion, Ohio, a town of under 1500 souls located west of Cleveland on Lake Erie.

The entire Vermilion kerfuffle resembled something out of a classic mystery novel, like Ngaio Marsh’s Overture to Death (1939) or Josephine Tey’s Miss Pym Disposes (1947), where rivalries and feuds among women in uncomfortably close proximity unexpectedly produce intense jealousies and bitter animosities. For months, it seems, members of the Vermilion chapter of Sorosis, a women’s literary and social club, had been receiving “vile and obscene letters,” newspapers breathlessly reported, “the contents of which cannot be decently repeated.” Most distressingly, it appeared certain that the anonymous writer came from within the hallowed confines of the Sorosis Club itself. (Ironically, the Sorosis Club–which on feminist impulse had been founded by professional women in New York in 1868, after the so-called “lesser sex” had been chauvinistically excluded from an audience event with famed visiting English author Charles Dickens–had been created in order to promote among women “mental activity and pleasant social intercourse.”)

Several outraged members of the Club who had received nasty letters—including Zella English, wife of Vermilion’s Congregational minister—collected samples of the writing of all the members of the Club and had them examined by experts from Cleveland, Chicago and New York. These experts unanimously pointed the finger of guilt at no less than the Sorosis Club president, Zenobia (Whitmore) Krapp, the forty-one year old daughter of the founder of Vermilion’s newspaper, George Whitmore, wife of local dairy farmer Fred Krapp and mother of a teenage girl. Indignant Club members promptly expelled Zenobia Krapp from their system, but that did not end the matter. The zealous Zenobia retaliated by filing a $10,000 defamation lawsuit against eleven of her former Club members.

And still the poison persisted, with several additional people receiving hateful anonymous letters, including Zella’s husband, Reverend English, and Mrs. Marvell Snyder, the newly-installed Sorosis Club president and wife of the local school superintendent. Marvell undauntedly reaffirmed her belief that Zenobia Krapp was the culprit, publicly declaring that the letters arose of the former president’s anger over not being asked to play the piano at a Sorosis Club sponsored church program. “Mrs. Krapp plays the piano,” Marvell explained phlegmatically. “There are several other Sorosis Club members who play it too, and in the opinion of some people they can play better than Mrs. Krapp. That’s what’s back of the whole thing.”

Currently I am unclear as to the outcome of the lawsuit, but Zenobia Krapp lived determinedly and apparently virtuously on in Vermilion for a half-century after the unpleasantness at the Sorosis Club, passing away at the age of ninety-one in 1984. Fifty years earlier, a final anonymous letter to Marvell Snyder had with unconscious irony advised the outspoken Vermilion matron, “Why not clean up your own doorstop and curb your tongue?” However, Marvell again bested her rival and got in the last word, so to speak, passing away in Dayton in the year 2000, fully sixteen years after Zenobia, at the advanced age of 104—by which time the poison pen letter had been superseded by noxious internet comments from odious online trolls.

****

Given these outbreaks of poison pen letters in the United States, France and England, which coincided with the onset of the Golden Age of detective fiction and its extensive exploration of “malice domestic,” it is only surprising that poison pen mysteries seemingly did not pop up sooner in crime writing. However, 1930 saw the inclusion of the short mystery problem “The Poison Pen Letters” in The Third Baffle Book, a collection of brainteasers produced by American publisher Doubleday, Doran’s Crime Club. The first poison pen mystery novel of which I am aware, English suspense queen Ethel Lina White’s Fear Stalks the Village, followed two years later. Then over the next decade came Dorothy L. Sayers’ landmark mystery Gaudy Night (1935), Henrietta Clandon’s Good by Stealth (1936), J. J. Connington’s For Murder Will Speak (1938) and Agatha Christie’s clever variant on the poison pen theme, The Moving Finger (1942). All of them were set, like Fear Stalks the Village, in England. (The Henrietta Clandon novel, a drolly ironic inverted mystery told from the twisted perspective of the poison pen writer, is being reprinted.) In 1937 a play, tellingly titled Poison Pen, was successfully staged by Richard Llewellyn, future bestselling author of How Green was My Valley (1939) and None but the Lonely Heart (1943). A fine film by the same title, starring Flora Robson, Ann Todd and Robert Newton, was adapted from Llewellyn’s play in 1939, three years before Henri-George Clouzot’s poison pen masterpiece Le Corbeau appeared in Vichy France. (Otto Preminger remade the latter film in the U. S. in 1951, under the title The 13th Letter.)

The first decade after World War Two seems to have been the high water mark for poison pen mysteries, with at least ten mystery novels on the subject published between 1946 and 1955, all of them taking place in England. Some of the most famous names in classic English mystery fiction—including John Dickson Carr (actually an American), John Street (writing as “Miles Burton”), Edmund Crispin, Gladys Mitchell, Nicholas Blake and Patricia Wentworth—contributed sinister tales of anonymous tattle-telling. Even children’s author Enid Blyton got into the wicked game, in more juvenile fashion, with The Mystery of the Spiteful Letters (1946). In Australian writer Max Murray’s clever The Voice of the Corpse (1948), set in the ingeniously named village of Inching Round, it is the objectionable writer of poison pen letters, Angela Pewsey, who is murdered.

The two-decade period from 1956 and 1976 saw the publication of poison pen mysteries set in France (Frank Horner’s The Devil’s Quill, 1959), and the Netherlands (Nicholas Freeling’s Double Barrel, 1964), as well as American Shirley Jackson’s classic, Edgar-winning short story “The Possibility of Evil” (1965) and Australian Mark McShane’s highly original The Crimson Madness of Little Doom (1966). English comic mystery writer Joyce Porter with Dover 3 (1965) had her egregious series sleuth match wits, in a matter of speaking, with an author of anonymous missives while W. J. Burley’s traditionalist mystery A Taste of Power (1966) returned readers to an enclosed English school setting somewhat reminiscent of that in Dorothy L. Sayers’ Gaudy Night. The late English author Robert Barnard provided a fine coda to vintage poison pen fiction with A Little Local Murder, which is set in the English village of Twytching. (Apt name that!) Barnard published this detective novel, his second in a long line, in 1976, less than a year after the death of Dorothy Myrtle Thurburn, the accused “unknown hand” behind the scores of poison pen letters that five decades earlier had so scandalized Sheringham. Too bad Dorothy did not live to tell the author, anonymously or otherwise, just what she thought of it.

Some Poison Pen Letter Outbreaks, 1909-1934

Elizabeth, New Jersey, United States, 1909-1914

Convicted: Anna (Dunn) Pollard

Tulle, France, 1917-1922

Convicted: Angele Laval

Northeastern United States, 1913-1923

Accused: George Maxwell

Sheringham, Norfolk, England, 1921-1925

Accused: Dorothy Myrtle Thurburn

Gien, France, 1929

Convicted: Martha Gitton

New Orleans, Louisiana, United States, 1934

Vermilion, Ohio, United States, 1934

Accused: Zenobia (Whitmore) Krapp

Two Dozen Vintage Poison Pen Mysteries, 1930 to 1976

“The Poison Pen Letters,” in The Third Baffle Book (1930), Lassiter McWren and Randle McKay

Fear Stalks the Village (1932), Ethel Lina White

Gaudy Night (1935), Dorothy L. Sayers

Good by Stealth (1936), Henrietta Clandon

For Murder Will Speak (1938), J. J. Connington

Poison Pen (1938), Richard Llewellyn

The Moving Finger (1942), Agatha Christie

The Mystery of the Spiteful Letters (1946), Enid Blyton

The Voice of the Corpse (1948), Max Murray

Night at the Mocking Widow (1950), John Dickson Carr

Groaning Spinney (1950), Gladys Mitchell

The Long Divorce (1951), Edmund Crispin

Beware Your Neighbor (1951), Miles Burton

Poison Pen at Pyford (1951), Douglas Fisher

The Dreadful Hollow (1953), Nicholas Blake

Welcome Death (1954), Glyn Daniel

Poison in the Pen (1955), Patricia Wentworth

The Devil’s Quill (1959), James Horner

Double Barrel (1964), Nicholas Freeling

“The Possibility of Evil,” (1965), Shirley Jackson

Dover 3 (1965), Joyce Porter

A Taste of Power (1966), WJ Burley

The Crimson Madness of Little Doom (1966), Marc McShane

A Little Local Murder (1976), Robert Barnard