Writer Varlam Shalamov spent 15 years imprisoned in Stalin’s gulags, first working arduous hours in a gold mine before getting a relatively easier position in medical services. Upon Stalin’s death, spurred by the dismantling of the prison camps and in an effort to preserve historical memory before it too could be erased, Shalamov set out to record his stories and memories of life in the gulag.

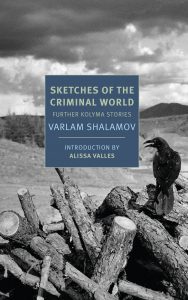

The following is an excerpt from Sketches from the Criminal World: Further Kolyma Stories, published this January by New York Review of Books. Sketches from the Criminal World is the follow-up to 2018’s Kolyma Stories, both named for the arctic prison camp of Kolyma, where winter lasted nine months out of the year and survival was a struggle at best, and often an impossibility. The essays and stories in these collections were composed between 1954 and 1973. The essay below is originally titled “How ‘Novels’ are ‘Printed.'”

***

Prison time is time prolonged. Prison hours are infinite because they are monotonous and have no story to tell. Life, displaced into an interval of time from reveille to end of work, is strictly regulated: it conceals an inner musical element, a certain even rhythm of prison life, which organizes a stream in the flow of individual mental shocks, personal dramas that have been imported from outside, from the noisy and varied world outside the prison walls. This prison symphony also includes a starry sky, divided into grids, and a flicker of sunlight bouncing off the rifle barrel of the sentry who is standing on the guard tower, a tower whose architecture resembles that of a skyscraper. This symphony also includes the unforgettable sound of the prison lock, its musical ring, like the noise made by ancient merchants’ chests. And many, many other things besides.

There are few external impressions in prison time, which is why time in prison later seems to be a black abyss, a vacuum, a bottomless pit from which your memory can only with a reluctant effort retrieve any event. That’s inevitable: after all, nobody likes to remember bad things, and memory, obediently carrying out its master’s secret will, pushes unpleasant events back into the darkest corners. Were they events, anyway? The scales of concepts have been changed, and the reasons for a prison quarrel that ends in bloodshed seem quite incomprehensible to an outsider. Later that time will seem to be blank and empty: time will seem to have flown by quickly, flying by all the quicker for the slowness with which it was dragged out.

But the clockwork is still something absolute. It is the source of order in the chaos. It is the geographical grid of meridians and parallels against which the islands and continents of our lives are mapped out.

This rule applies to normal life, too, but in prison its essence is more exposed and more undeniable.

It is these long prison hours that thieves try to shorten by their “memoirs,” and not only by mutual boasting, monstrous bragging, when they colorfully describe their robberies and other adventures. Those stories are fiction, artistically simulated events. Medicine has the term “aggravation”: exaggeration, when a trivial illness is presented as serious suffering. Thieves’ tales are like this aggravation. A pennyworth of truth is turned into a silver ruble to be exchanged in public.

A gangster talks about whom he ran around with, where he used to steal, and provides his unknown comrades with a reference for himself; he talks about breaking into unbreakable Miller safes, when in fact his burglaries went no further than stealing clothes from a wash line at a suburban cottage.

The women he has lived with are extraordinary beauties, virtual millionairesses.

There is something more important and, in essence, dangerous in all this fibbing, these mendacious memoirs, quite apart from a certain aesthetic enjoyment of the process of storytelling—a pleasure for both storyteller and listener.

The fact is that these prison hyperboles are the criminal world’s propaganda and agitation material, and the material is quite significant. These stories are a gangster’s university, a faculty of their terrible science. Young thieves listen to their elders and reaffirm their faith. Reverence for heroes of nonexistent exploits is instilled into young minds, and they themselves dream of achieving the same. This is the neophyte’s initiation taking place. The young criminal remembers these teachings for the rest of his life.

Perhaps the gangster storyteller actually wants, like Gogol’s Khlestakov, to believe in his inspired lies. They make him feel stronger and better.

Finally, when a gangster’s acquaintance with his new friends is sealed, when the oral questionnaires of the new arrivals have been filled in, when the waves of bragging die down and some episodes of the memoirs, the most spicy, have been repeated twice and committed to memory so that any one of the listeners will in different surroundings present someone else’s adventures as his own, all the same the prison day seems never-ending. Then suddenly someone has a good idea: “How about printing a novel?”

Some tattooed figure then climbs out into the yellow light of the electric bulb, a light of so little candlepower that it is difficult to settle down to reading: the figure then begins with his gabbled “debut,” which resembles the usual opening gambit of a chess game: “In the city of Odessa, before the revolution, there lived a famous prince and his beautiful wife . . .”

“Printing,” or literally “churning out,” means “retelling” in gangster language, and the origin of this colorful slang term is easily guessed. A retold novel is a sort of oral offprint of a narrative.

“Printing,” or literally “churning out,” means “retelling” in gangster language, and the origin of this colorful slang term is easily guessed. A retold novel is a sort of oral offprint of a narrative.The novel in this case does not need to be a novel, a tale, or a story in accepted literary forms. It can also be any memoir, movie, or historical monograph. The criminal’s novel is always someone else’s anonymous work, expounded orally. Nobody ever names or knows the author.

It is essential for the story to be long: after all, one of its purposes is to pass the time.

Such a novel is always half improvised, since it was heard somewhere else and partly forgotten, partly embroidered with new details, the color depending on the storyteller’s abilities.

There are several particularly widespread and popular novels, as well as some scenario outlines that even the Semperante improvisation theater would have envied.

These favorites are, of course, detective stories.

It’s a curious fact that modern Soviet detective stories are completely rejected by the thieves. Not because they lack ingenuity or talent: the things the thieves do listen to are even more primitive and mediocre. In any case it is up to the storyteller to make up for what Adamov’s or Sheinin’s stories lack.

No, the thieves are simply not interested in modernity. “We know our own lives better,” they say, and rightly so.

The most popular novels are Prince Viazemsky, The Jack of Hearts Club, the immortal Rocambole—the remains of the amazing Russian and foreign pap that Russians read in the nineteenth century, when not only was Ponson du Terrail considered a classic but so was Xavier de Montépin and his multivolume novels The Detective Murderer and An Innocent Man Executed, etc.

Among the plots taken from good-quality literary works, The Count of Monte Cristo used to have a solid place; on the other hand, The Three Musketeers was a total failure and was treated as a comic novel. So the idea of a French director to film The Three Musketeers as a merry operetta must have had a sound basis.

No mysticism, no fantasies, no psychology: strong plots and naturalism with a sexual bent—that was the slogan for gangsters’ oral literature.No mysticism, no fantasies, no psychology: strong plots and naturalism with a sexual bent—that was the slogan for gangsters’ oral literature. One of these novels, if you listened closely, showed that it was derived from Maupassant’s Bel Ami. Of course, the title and the heroes’ names were quite different, and the plot itself was subjected to considerable changes. But the basic structure, the career of a pimp, remained.

Anna Karenina was reworked by the gangster novelists in exactly the same way as it was when it was staged by the Moscow Art theater. The whole Levin-Kitty plot was swept aside. Without its scenery and with the heroes renamed, the novel made a strange impression. Passionate love, arising instantly. A count squeezing (in the literal sense of the word) the heroine at the entrance to the railway carriage. The errant mother visiting her son. The count and his mistress on a spree abroad. The count’s jealousy and the heroine’s suicide. It was only the wheels of the train, Tolstoy’s rhyme for the railway carriage, that told you what was going on.

Les Misérables was a story that people were happy to tell and to listen to. The author’s mistakes and naïvety in portraying French criminals was condescendingly corrected by Russian gangsters.

Even the biography of the poet Nekrasov (apparently using one of Kornei Chukovsky’s books) was used to concoct an absolutely amazing detective story with Panov (Nekrasov’s pseudonym) as the main hero.

These novels were narrated by the thieves who liked them, but mostly in a monotonous and boring voice: it was uncommon to find a gangster storyteller who was the sort of artist, or born poet, or actor capable of bringing any plot to life with a thousand surprises. If such an expert was found, all the gangsters who happened to be in the prison cell at the time would gather around to listen. Nobody would go to sleep until morning, and the expert’s underworld fame would reach a long way. The fame of such a novelist would be not less but rather greater than that of any Kaminka or Andronikov.

In fact, every storyteller was called a novelist. This was a concept with a definite meaning, a term in the criminal vocabulary: “novel” and “novelist.”

The novelist or storyteller was, of course, not necessarily a criminal. In fact a noncriminal, freier novelist was even more highly valued, for the stories he could tell were stories that criminals could give only in a limited range, just a few popular plots, nothing else. It was always possible that a new man, an outsider, might have memorized some interesting story. If he was able to tell this story, then he would be rewarded by the old crooks’ patronizing attention, for art wasn’t enough to save your clothes or your parcel from home. The Orpheus legend was just a legend, after all. But if there was no real cause to fight over, then a novelist would get a place on a bunk next to the gangsters and an extra bowl of soup at dinner.

But it would be wrong to assume that novels existed only to while away prison time. No, their significance was greater, deeper, more serious, more important.

The novel was virtually the only way in which gangsters came into contact with art. The novel responded to the gangster’s monstrous but powerful aesthetic needs: he didn’t read books, magazines, or newspapers; he “scoffed his culture” (a special expression) in this oral form.

Novels are, as it were, a sacrosanct part of the thieves’ confession; they are included in his code of conduct and his spiritual needs.Listening to novels is a sort of cultural tradition highly respected by gangsters. Novels have been recited since time immemorial; they are sanctified by the entire history of the criminal world. That is why it is considered a sign of good manners to listen to novels, to love and patronize this sort of art. The gangster is a traditional Maecenas to novelists; he’s brought up to like them, and nobody will refuse to listen to a novelist, even if they are bored to tears. It’s clear, of course, that robberies, thieves’ discussions, and the obligatory passionate interest in cards, with its unbridled recklessness, are all rather more important than novels.

Any minute of leisure puts people in the mood for novels. Card games are forbidden in prison, and although a pack of cards can be manufactured with incredible speed using a piece of newspaper, a stub of an indelible pencil, and a bit of chewed bread—this shows the thousand years of experience of generations of thieves—it’s still not always possible to play cards in prison.

No criminal will ever admit he doesn’t like novels. Novels are, as it were, a sacrosanct part of the thieves’ confession; they are included in his code of conduct and his spiritual needs.

Criminals don’t like books or reading. Very seldom does one come across any who have been taught from childhood to love books. Such “monsters” read virtually in secret, hiding from their comrades, for they are afraid of biting, coarse sarcasm, as if they were doing the devil’s work, something unworthy of a gangster. Gangsters hate intellectuals because they envy them: they feel any unnecessary education to be something foreign, alien. And yet it is Bel Ami or The Count of Monte Cristo, as they appear in their novel version, which arouse general interest.

Of course, a reading gangster could explain to a listening gangster what it was all about, but . . . traditions are very powerful.

No literary historian, no writer of memoirs, has even touched on this variety of oral literature, which has existed from time immemorial to our own times.

Using the old crooks’ terminology, “novels” are not only novels, and what matters is not just the way they stress the word, as róman instead of román. Even a literate chambermaid, carried away by Anton Krechet, or Nastia in Gorky’s story, spending her time reading Fateful Love, got the stress wrong.

“Printing novels” is the most ancient of thieves’ customs, with all its religious obligations, which are part of the gangster’s credo, along with playing cards, drunkenness, debauchery, robbery, escape attempts, and courts of honor. This vital element of the criminal way of life is their equivalent of fiction.

The concept of a novel is fairly broad. It includes various prose genres: the novel, the tale, and any short story, authentic ethnographical essays, theater plays, radio plays, and a retelling of a movie someone has seen, the language rendered from screenplay into libretto version. The outline of the plot is interwoven with the storyteller’s improvisations: strictly speaking, a “novel” is a momentary creation, like a theater performance. It happens just once and becomes even more ephemeral and fluid than an actor’s art on the stage, for the actor is still keeping to a fixed text that the playwright gave him. In the well-known “theater of improvisation” there was far less improvisation than in any prison or camp “novel.”

The older novels, like The Jack of Hearts Club or Prince Viazemsky, have long vanished from the Russian reader’s market. Historians of literature will sink no lower than Rocambole or Sherlock Holmes.

Nineteenth-century Russian pulp fiction still survives in the gangsters’ underground. These are the old novels that criminal novelists tell (or “churn out”). They are criminal classics, as it were.

Nineteenth-century Russian pulp fiction still survives in the gangsters’ underground. These are the old novels that criminal novelists tell (or “churn out”). They are criminal classics, as it were.A freier storyteller, in the overwhelming majority of cases, can retell a work that he read on the “outside.” To his own great amazement, it is in prison that he first finds out about Prince Viazemsky, after he has heard it from a criminal novelist.

“It happened in Moscow, on Razguliai; Count Pototsky often came to a high-society ‘hideout.’ He was a healthy young man.”

“Slow down, slow down,” the listeners say.

The novelist slows down the tempo. He usually goes on telling the story until he is completely exhausted: until at least one listener has fallen asleep it is considered indecent to break off the story. Decapitated heads, packets of dollars, jewels found in the stomach or intestines of some high-society “Marianne” come one after the other in the story.

Finally, the novel is over, and the exhausted novelist clambers back to his place, while the satisfied listeners unfold their colorful quilted blankets—essential possessions in the life of any self-respecting gangster.

That’s what a novel is like in prison. It’s different in the camps.

Prison and labor camp are different things, quite unlike each other in their psychological content, despite seeming to have much in common. Prison is far closer to ordinary life than camp life.

The almost invariably innocent, amateur literary aura that being a novelist has for a freier in prison suddenly takes on a tragic and ominous nuance.

You might think that nothing has changed. The same gangsters who ask for the stories, the same evening hours for telling them, the same subjects for novels. But now novels are recited for a crust of bread, for a gulp of soup poured into your tin mug from an empty tin can.

Here there are more novelists than anyone needs. Dozens of hungry men have a claim to that crust of bread or gulp of soup; there were cases when a half-dead novelist collapsed, unconscious from hunger, in the middle of the story. To prevent such cases, the custom arose to let the next novelist have a sip of soup before he “churned.” That sensible custom became fixed.

In the crowded camp’s solitary cells, like a prison within a prison, the gangsters were usually in charge of distributing food. The administration hadn’t the strength to do battle with that way of doing things. After the gangsters had their fill, the rest of the barracks would then get to eat.

An enormous earthen-floor barracks was illuminated by a smoking kerosene lamp.

Everyone except the thieves had done a full day’s work, spending many hours in the icy cold. The novelist wanted to get warm, to sleep, to lie down, to sit down, but even more than sleep, warmth, and peace, he wanted food, any food. By an unbelievable, fabulous effort of will, he mobilizes his brain for a two-hour novel to give the gangsters pleasure. And as soon as he finishes his detective story, the novelist sips his “gulp of soup,” which is now cold and covered with a crust of ice, and then laps up and licks the homemade tin mug until it is dry. He doesn’t need a spoon: his fingers and tongue will be more use to him than any spoon.

In total exhaustion, in constant vain efforts to fill, if only for a minute, his shrunken stomach, which is now devouring itself, a former university lecturer offers himself as a novelist. He knows that if he is successful and his customers approve, he will be fed and protected from beatings. The professional criminals believe in his storytelling abilities, no matter how emaciated and exhausted he is. In the camps people don’t judge others by their clothes, and any “scruff” (a colorful term for a bedraggled individual dressed in torn rags, with the cotton-wool padding sticking out from all over his pea coat) may turn out to be a great novelist.

Having earned his soup and, if lucky, a crust of bread, the novelist shyly chomps it in a dark corner of the barracks, arousing his comrades’ envy, for they don’t know how to churn out novels.

If he is even more successful, the novelist will be treated to some tobacco, too. That is the height of bliss! Dozens of eyes will watch his trembling fingers rubbing the tobacco and rolling a cigarette. Should the novelist clumsily spill a few precious flakes of tobacco on the ground, he may burst into real tears. How many hands will be stretched out in the darkness toward him, so as to light up his cigarette with a coal from the burning stove and, as they light it up, at least get a breath of tobacco smoke. And quite a few pleading voices behind his back will utter the tried and tested formula, “Let’s have a smoke,” or use the mysterious synonym of this formula, “forty . . .”

That’s what the novel and the novelist are like in the camps.

From the day the novelist enjoys success, nobody will be allowed to upset him, or to beat him: he’ll even be given bits and pieces to eat. He can now boldly ask gangsters for a smoke, and they will leave him their stubs: he will now have won a position at court, and will wear a gentleman-in-waiting’s uniform.

Every day he has to be ready with a new novel—there’s a lot of competition—and it will be a relief for him one evening when his masters are not in the mood for cultural nourishment, not in the mood to “scoff culture,” and he can sleep the sleep of the dead. But his sleep may, however, be roughly interrupted if the criminals have a sudden whim and decide to cancel their game of cards (something that happens very seldom, for a game of bezique or blackjack is far more precious than any novel).

Among the hungry novelists you meet ones with ideas, especially when they have had several days of being fed. They then try to tell their listeners something a bit more serious than The Jack of Hearts Club. This sort of novelist imagines he is a cultural worker to the thieves’ throne. Such people include former writers, proud of their fidelity to their true profession, which now finds an outlet in such unlikely circumstances. There are some who imagine they are snake charmers, flautists playing music to a swirling cluster of poisonous reptiles . . .

Carthage is to be destroyed!

The criminal world is to be exterminated!

(1959)

__________________________________