While Pupetta sat in prison for killing her first husband’s assassin, her guards had to play traffic cop to the many suitors who clamored to visit her. Love songs and poetry were written about this brave and beautiful murderess, and she reveled in the attention she says helped her bide the time.

Pupetta shuddered when I asked her about raising a baby in Naples’ notorious Poggioreale prison. She was allowed to keep him in her dark corner cell until he turned four. I told her about my own children, both sons, and she asked to see photos of them. As I scrolled through some old ones I kept on my phone, she seemed grandmotherly. I explained to her that my children were raised in Italy while their grandparents lived in the United States and Canada, and that they had just a passing relationship with them, which had always made me sad. She then told me about her own grandmother’s disappointment that she had married Pasqualone, how her grandmother had hoped that Pupetta might meet someone outside the usual crowd, which I took to mean the criminal underworld.

“I disappointed her,” Pupetta said. “I have never been judgmental about what my own children choose to do because I was so hurt that she didn’t respect my choices.”

After I left her house, I looked up her family history to learn that both of her grandmothers had died in the 1940s, long before Pupetta would have ever met Pasqualone. What was the purpose of the lie, I wondered. Was it to get me to trust her, or had she confused the grandmother with an aunt or other female relative she held in high esteem? At the time I thought that maybe she just wanted to be relatable, but surely she knew I would check her every story. When I went back for what at the time I did not know be our final visit before her daughter, Antonella, told me never to come back, I asked Pupetta whether the grandmother who had disliked Pasqualone was maternal or paternal— I hadn’t asked at the time. She looked at me and smiled and quickly dismissed the subject.

Raising a child in a prison as hard as Poggioreale gave Pupetta certain perks other inmates didn’t have, even though the circumstances made the experience anything but joyful. Unlike the general female population, who lived in large dormitory style rooms with triple bunk beds and a single toilet in the corner, incarcerated mothers were given single- or double-occupancy cells with wooden boxes on the floor beside their beds, inlaid with tiny mattresses for their babies. Pasqualino had a small selection of toys and a few books, and she got to take him out to play in the prison playground once or twice a day. But Pupetta mostly made up games to play or sang to him as they sat together on the cold cement floor of her cell.

Pasqualino’s first friends were the children of other incarcerated mafia women, many of whom were serving short sentences as accomplices or accessories to crimes committed by their men. After they got out, they didn’t forget the godmother in the corner cell. Pupetta laughed as she recounted some of the things her former inmate girlfriends snuck into Poggioreale when they visited her, from local white wine to truffles. She was the rare female inmate locked up in the 1950s for murder. Her long sentence gave her seniority, and her crime garnered automatic respect from all the new inmates.

She had done a man’s job by avenging her husband’s death and there were no other women who could say the same. In a crime school like this, she was both valedictorian and class bully. The other inmates did her bidding, and even changed Pasqualino’s soiled diapers during open recreation time or babysat when she needed a break from his crying. The stories of her incarceration that were published at the time vary in remarkable ways from her own memory, or the stories she chooses to tell. Undoubtedly it is one’s right to recast their own story—even one that has been lived in crime dockets like Pupetta’s—but the ease with which she chooses to rewrite hers entirely is sometimes mind-boggling.

What is known for sure is that during her incarceration, wedding proposals and gifts floated in from the outside almost daily, mostly from Camorristi who wanted to latch on to her rising star when she got out. But it was inside where she flexed her muscle as she ruled the top of the hierarchy among the imprisoned wives and girlfriends. She set up a system inside much like her late husband’s on the outside, in which she doled out “favors” to inmates who could then source information from their own visitors about what was happening on the outside, which Pupetta would pass along to favorable clansmen of her choice.

On Pasqualino’s fourth birthday, he was taken from Pupetta’s jail cell to start school and live with her mother. By the time Pupetta got out of prison, when Pasqualino was ten, he was calling his grandmother “Mamma.”

Freed, Pupetta was clearly ready to move on and start her new life, describing her release from prison as something of a rebirth. At the time she sought out the press, gave interviews to show that she was back, and courted various directors, trying to carve out a new career in film. “It was both terrifying and liberating,” she explained to me. She gave a number of interviews in which she berated the prison system, its treatment of her and other inmates, even though she had earned a number of special privileges during her final years inside. After so many years away at “crime school,” rehabilitation was not to be part of that new beginning, even though she says she had fully intended to live a cleaner life when she got out of prison. She felt no remorse whatsoever for the murder she’d committed, in fact she has always said she would do it again, even now in her eighties. She felt that it was her duty, which was a mix of her father’s principles and her newlywed husband’s influence over her. Had she not killed Big Tony, she would have likely been shuffled off to marry an associate, forgotten forever, reduced to being just another Camorristi wife. Pupetta wanted a different legacy. She did not need to avenge her husband’s death. Society did not demand it of her, especially in the 1950s. Without the influence of social media and the Internet, she acted in a vacuum and could have easily gotten away, quite literally, with murder.

There was a sense in the way she presented herself both in person and in recent media interviews that she had even fewer regrets in old age, that somehow her life had been well lived. There is no question that she enjoyed her notorious legacy, and I am completely convinced she would have reveled in the fact that the police in Naples prohibited a public funeral for her when she died. When I went to her gravesite to lay flowers, I was told I could not, that her life could not be celebrated, that too many “mafiosi” are sent off gloriously. I know she would have loved to be considered too important to be celebrated publicly. I left the flowers on a nearby grave.

One can only imagine a figure like Pupetta in the age of Instagram. She was able to create an alluring image of a woman in complete control, with her leather dresses, choke collars, and lowcut blouses, without a single follower or like. She often said to me, “Tell the Americans this,” when she told me a story. I often thought she would love the idea that people outside Italy would read about her.

She could summon the press, attract multiple men, and make decisions people listened to, despite the fact that she was a woman who nobody believed could actually be part of the mafia. As prosecutor Cerreti saw it, though, Pupetta was an early influencer of her own. She knew well that the image of the brazen “mafia woman” would carry some clout in the outside world, even if she possessed little in the way of organizational authority to back it up. “She is a self-made woman in many ways, both when she committed murder and how she chooses to portray herself today,” Cerreti told me.

A few years after Pupetta’s release in 1965, one of the women she had befriended in prison set her up on a blind date with Umberto Ammaturo, a square-jawed Camorra underboss with dark wavy hair. He groomed his thick sideburns to perfection with a straight razor he is rumored to have used to carve up more than one enemy. He was not her beloved Pasqualone, but he was sexy, and after all that time in prison Pupetta was lonely. More important, he was a Camorra underboss—meaning that settling on him would not result in her stepping backward from Pasqualone’s standing. That said, she might have taken Ammaturo’s nickname, ’o pazzo, “the crazy one,” as a warning of what was to come.

As handler of the Camorra’s emerging cocaine routes in and out of South America, Umberto was fluent in Spanish. He was also hotheaded. He had a short temper that Pupetta said often turned to violent outbursts against her and Pasqualino, who had moved back in with her when she left prison.

Umberto had started his criminal career as a guaglione, essentially a street kid who pickpocketed tourists and stood as a lookout for cops in order to warn the bigger criminals. He caught the eye of more seasoned men, who admired his deviance. He quickly climbed the criminal ladder, advancing to a full-time cigarette smuggler for the Camorra in the early 1960s.

He had connections to Tommaso Buscetta, one of the Sicilian Mafia’s most notable turncoats, who is personally responsible for the dismantling of the Cosa Nostra in the 1990s by testifying in Italy’s so-called Maxi Trials. After Buscetta died of cancer, it was revealed that he and his family had gone to live in Florida under new identities with full police protection for many years. Buscetta had testified against some of the biggest mobsters in Sicily and the United States in epic hearings that ran from February 10, 1986, to January 30, 1992.

Those trials led to a number of American mafia arrests and launched the career of one young district attorney in New York named Rudolph Giuliani. Thanks to Buscetta and another turncoat’s testimony, 338 people were convicted and sentenced to a total of 2,665 years in prison. (Giuliani went on to become one of the most successful anti- mafia prosecutors in US history and brought hundreds of criminals to justice.)

Umberto and Pupetta hit it off immediately. A few months after they started a relationship, Pupetta, at the age of thirty-one, was pregnant with twins. Not long after Antonella and Roberto were born, Umberto was arrested in Naples with the Camorra’s top man, who lorded over the various emerging criminal enterprises in northern Italy. The two were charged with smuggling cocaine from Latin America via the diplomatic mail pouch of Panama’s consulate in Milan. During the ensuing trial, Umberto faked a number of health conditions, including insanity, with the help of the Camorra- friendly forensic psychiatrist Aldo Semerari. Thanks to the crooked doc, Umberto ultimately escaped hard jail time and was sentenced to a psychiatric hospital— from which he quickly escaped.

Pupetta and Umberto never married, but they worked hard to elevate their joint criminal interests during their first years together. In November 1967, Pupetta was convicted of receiving stolen goods when a hundred shirts mysteriously arrived at the clothing shop she had recently opened in Naples without an invoice or purchase order, either of which would have required her to pay tax. She was acquitted of delinquent activity and never served her three-month sentence. She was investigated numerous times throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s and frequently found herself on the periphery of a variety of crimes.

When Pasqualino reached his teens, there was tension in the house. Pupetta’s firstborn was handsome and built like his robust dad, and Pupetta often reminisced about her dead husband when her son turned a certain way or smiled just so. Pasqualino started to rebel and compete with Umberto, who didn’t like the constant reminder of Pupetta’s previous life. Pasqualino’s temperament didn’t help, and he often lashed out about how his mother’s lover would never be a replacement for his own dead father—a man Pasqualino had never met.

When he started mouthing off to Umberto and eventually threatened to avenge the death of his father— a job his mother had taken care of just fine— the tension in the household reached a boiling point.

In 1972, a few days after Pasqualino’s eighteenth birthday, Umberto set up an appointment with him under the guise of a truce, offering to help the budding criminal develop some of his own contacts within the construction arm of the Camorra. The two made plans to meet at a dusty Neapolitan construction site where a new tangenziale, toll bypass, was being built. The superhighway would allow travelers to skirt the stifling Neapolitan gridlock to reach the Amalfi Coast and deep southern provinces more quickly. It would also line the pockets of dozens of Camorra clans that had infiltrated nearly every aspect of the project.

The meeting happened to be on the day that crews were pouring the cement foundation for the supporting pillars of the massive four-lane highway. There were more than a dozen mixer trucks working furiously to set the steel framework into deep pockets that had been dug into the lower foothills of Mount Vesuvius. The hot wind blew thick clouds of dust through the site as the noisy trucks rolled in and out.

Pasqualino was never seen again after that day, in a vanishing act that had all the markings of what the Camorra calls a lupara bianca—an assassination carried out with such precision that there is no trace of the body left at all.

As is so often the case in crime families, life becomes a sort of currency that can be easily spent or saved depending on a variety of circumstances. Pupetta would not talk to me about the disappearance and presumed murder of her son by her lover, brushing off each question with the flick of her black-manicured hand, assuring me that I can look it up. “I’ve talked about it too much already,” she said.

Without a confession—which, until her death, she still hoped would one day come from a turncoat—she had no choice but to assume her son’s grave is under the base of the tangenziale pillar. She would not confirm to me whether she was responsible for the flowers that appeared there every year on Pasqualino’s birthday—until the area became a rogue dumping ground for the mob’s toxic garbage enterprise.

Despite the assumptions Pupetta harbored, she and Umberto still went on to forge a criminal coupledom that eventually landed them a joint conviction for the murder and decapitation of Aldo Semerari, the shady shrink who helped spring Umberto from prison by signing off on his phony mental illness years earlier.

Semerari disappeared under suspicious circumstances from the Royal Hotel in Naples in late March 1982. His body, from the neck down, was found a week later in the trunk of a burned-out car with his decapitated head on the front seat. He had been tortured, based on the broken bones and cuts, and hung upside down to bleed out, undoubtedly while he was still alive—an extra cruel touch that was meant as a warning for others. When I asked a forensic scientist how difficult it would have been for Pupetta and Umberto, working separately or together, to behead the doctor, I was told they would likely have needed to use an electric saw, which cuts through bone much more easily than a blade. The fact that Semerari had no blood left in his body would also have made it an easier— and cleaner— job.

A day later, Semerari’s personal assistant, Fiorella Carrara, was found dead in her home with a Magnum .357 sticking out of her mouth. Her death was classified as a suicide, even though her fingerprints were not on the gun and she left no note, and three days after her body was discovered her home was ransacked and storage boxes were mysteriously removed from her attic. The investigation into Semerari’s decapitation initially focused on his political ties, but quickly turned to Pupetta and Umberto as primary suspects.

Semerari had ties to Italy’s far-right movement, which was involved in a string of nationwide terrorist attacks during a two-decade period referred to as the Years of Lead, so called for the sheer number of bullets used in terrorist attacks during the late 1960s to the 1980s. At the time, extreme right-wing and left-wing organizations were waging a war on the establishment—and on each other. The unrest wasn’t mafia related, but there were a number of people like Semerari who had their fingers in both pools of blood. Semerari was also a member of the Propaganda Due Masonic lodge, which included several of Italy’s most prestigious secret service members. It included a few holdout Americans who were stationed in Italy after the war to keep communism at bay, and also had charter lodges in Brazil and Argentina. The lodge counted up- and- coming politician Silvio Berlusconi, who would later become one of Italy’s longest-serving prime ministers, on its roster. The Freemasons— much like the mafia and even the Catholic Church— didn’t allow women to be members, but many were loosely associated, albeit on the periphery. The many alliances forged by the lodge likely kept Semerari out of jail, and many initially assumed they led to his death.

Pupetta adamantly denies any role in murdering and decapitating Semerari, though she did describe Carrara to me as a putana, “whore.” She described Semerari as a traitor for helping their rival Raffaele Cutolo, underscoring the extent to which she and Umberto had a motive to kill him. Betrayal in crime circles is without question the greatest unforgiveable sin, and even though Umberto eventually betrayed Pupetta and the larger circle, he, too, found Semerari’s betrayal in helping Cutolo a step too far.

___________________________________

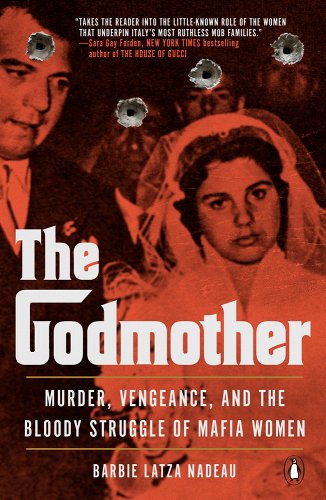

Excerpted from The Godmother: Murder, Vengeance, and the Bloody Struggle of Mafia Women, by Barbie Latza Nadeau. Published by Penguin Books. Copyright, 2022. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.