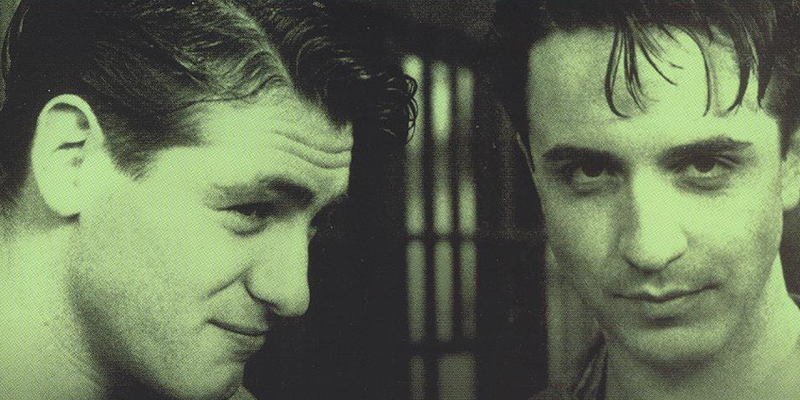

In 1992, two of the year’s most memorable independent films depicted gay men committing murder. Gregg Araki’s The Living End and Tom Kalin’s Swoon arrived at the peak of what critic B. Ruby Rich coined the “New Queer Cinema”, an informal movement of transgressive, formally inventive films from young queer filmmakers, usually with a political or historical bent. Araki and Kalin’s films were representative of one of the major strains of New Queer Cinema—centralizing queer villains from a queer point of view. The Living End is a jagged, Godard-esque lovers-on-the-run film with an HIV-positive couple at its center. While The Living End raged at contemporary oppression, Swoon examined the Jazz Age-killers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, a wealthy young couple who killed a child to achieve the “perfect crime,” and became the victims of a breathlessly watched trial.

Thirty years later, the thorny characters and violent acts that characterize these films render them still potent and disquieting. If The Living End and Swoon were powerful pieces of art in 1992 because they were impassioned and incisive responses to AIDS and decades of legal and social oppression, these films are powerful now partially because of how queer media has changed in the interim. After decades of assimilative legal successes and the growing presence of queerness in pop culture, debates over queer cinema are now centralized around mainstream representation in corporate-backed film and television. Films like Kalin’s and Araki’s can remind us that independent voices provide avenues for inventive forms and challenging content that can be hard to come by in 2022.

The Living End is a vessel for big emotions and big ideas.The Living End is a vessel for big emotions and big ideas. Its style is unrestrained, characterized by loud music, saturated colors, sudden violence, and frank eroticism. Its protagonists (named Jon and Luke, one of many nods to Jean-Luc Godard) openly philosophize: Jon, processing his recent positive HIV test, journals into a tape recorder about how “death is weird” and later discusses his disbelief in an afterlife, while Luke makes sweeping statements about choosing a life of “absolute freedom” in the face of imminent death. In this sense, the film follows in the tradition of road movies that use the conceit of a couple on the run from the law to examine social issues. Here, the inextricably linked issues were the ongoing AIDS pandemic and pervasive homophobia in government and in social life.

Jon and Luke’s odyssey begins when Luke urgently hitches a ride from Jon, after having killed a group of homophobes who attempted to attack him. They quickly fall into a relationship, and after Luke kills a cop, Jon agrees to drive him out of town, no destination in mind. The plot never builds to a fever pitch as in comparable films like Bonnie and Clyde and Thelma and Louise, because we never get any indication that the police are actually on their trail. Instead, Araki trains his gaze on how their bond shifts and changes in response to interpersonal dynamics, while also examining how the effects of legal and social homophobia affect every facet of their lives.

Luke acts as an informal vigilante against these forces. We see him kill numerous vocal homophobes over the course of the film, and the other targets of his actual or fantasized violence are usually politicians and cops. As Luke’s unpredictable crimes increase, his hedonistic “absolute freedom” philosophy begins to seem like a put-on—his crimes are driven not just by impulse, but by long-simmering rage at societal bigotry and abandonment. Jon, who’s initially taken with Luke’s spontaneity in contrast with his own tortured rumination, grows tense and exhausted as Luke’s actions put them in danger with increasing frequency. Their blissful escape from quotidian reality develops its own dangers: Luke has a death wish, and Jon would rather leave Luke behind than help him fulfill it. The film’s despairing ending sees Luke, having knocked Jon out and tied him up to prevent him from leaving, rape Jon on a beach while he holds a gun in his own mouth (he previously told Jon he wanted to die mid-climax). When he attempts to fire, the empty gun clicks. Deprived of his plotted death, he’s left alive with nowhere to go, and so lets Jon go and slumps away from him. Jon hits him, walks away, then comes back to lean against Luke as the sun sets. There’s no resolution in this end, no pat conclusions, no moral clarity. Araki provokes the viewer to consider what a queer identity and a positive HIV diagnosis entail for one’s life and place in society—when a person is faced with a potentially terminal diagnosis, hostility in public life, abandonment by the government, and an expectation to live life as normal, what future does that lead a person toward?

If Araki’s film mostly shows Luke and Jon as sympathetic characters, committing and aiding crimes out of a mixture of righteous anger and desperation, Tom Kalin’s Swoon paints a more unsettling picture. Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb were actual people who murdered a child, Loeb’s cousin Bobby Franks, as an experiment to prove they were Nietzschean supermen, individuals who exist on a higher plane than the average human and can therefore transgress laws and social norms. Kalin does not engage in image rehabilitation or stress that we should empathize with the couple, rather, he primarily asks us to consider the legal and social ramifications of their crime.

The film, with an aesthetic defined by elegantly composed frames and Ellen Kuras’s chiaroscuro black-and-white cinematography, is methodically paced. Kalin takes us through Leopold and Loeb’s domestic life of intermittent sex and petty crimes; the murder; the discovery of evidence; police interviews; the trial; and the lives of Leopold and Loeb behind bars, culminating in Loeb’s murder by another inmate and Leopold’s eventual release. Each event is given the same emphasis, and one logically builds to another, allowing the viewer to see the accrual of details that build to a jarring picture of a violent couple whose crime exposed and nourished widespread bigotries. The couple themselves, even before the murder, aren’t particularly sympathetic—Loeb is thoughtless and crime-obsessed, and Leopold is self-important and obsessive. The murder itself is brief, shocking, and bloody, and their disposal of the body reveals both their carelessness and lack of remorse. When the police catch on, mostly because Leopold left his glasses at the scene of the crime, both instantaneously claim that the other committed the crime. We are thus primed to view them as objects of fascination, but not sympathy, by the time the trial occurs.

Kalin implicitly embedded commentary on contemporary criminalization of homosexuality.The trial marks a shift in Kalin and co-screenwriter Hilton Als’s narrative schema from a psychological portrait to an institutional critique. The prosecutors argue that they were motivated by “unnatural lusts” and erroneously claim that Leopold and Loeb sexually abused Franks. Their defense engages a psychologist to contextualize their crimes, who dissects Leopold’s sexual obsession with Loeb. Here, Kalin places Leopold and Loeb laughing and undressing in bed in the middle of the frame—a clear visual signifier that they are not on trial for an act of violence, but for all-consuming “perversion”. In a 2019 interview, Kalin and interviewer Leah Rosenzweig discussed how the scene reflects the 1986 Supreme Court case Bowers v. Hardwick, which upheld a Georgia law prohibiting sodomy. Through an interpretation of a historical trial which sensationalized and punished queerness, Kalin implicitly embedded commentary on contemporary criminalization of homosexuality.

The scenes that follow build on this critique. After they are sentenced, Kalin presents a montage of headshots in profile with notes denoting their phrenological traits—a deviant brow here, an aggressive nose there. A voiceover explains how the facial features of Leopold and Loeb caused their “criminal urges.” Later, after Loeb’s killer is quickly acquitted by a jury when he claims Loeb propositioned him, Kalin cuts to a man reading aloud a news story detailing the event, describing the killer as a “Negro” who brutally attacked Loeb after incessant sexual pressuring (despite the assailant being white, and the evidence strongly pointing toward Loeb’s killer being the instigator). Both scenes stage the panicky spin which followed the Leopold and Loeb trial. Pseudoscientific arguments about their innate criminality and perversion were offered up to explain their actions—and thus criminal behavior writ large—and the killing of Loeb is distorted to reinforce preexisting sexual and racial assumptions. Despite its period setting, Kalin created in Swoon a sharp perspective on how marginalized people are blamed for crime and social dysfunction, with a particularly pointed view on how queer sex is treated as a sinister act on par with murder.

If The Living End depicts violent crime as an impulsive response to suffocating oppression, and Swoon shows that anti-normative sexuality can be a crime in itself, then together they provide a disquieting picture of the structures and consequences of homophobia. Despite legal victories and cultural assimilation in the interim, these structures have not entirely abated since 1992, and we now find ourselves in the midst of political and cultural backlash toward LGBTQ+ communities—see, for instance, Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill, censorship of queer literature, and legislation blocking healthcare for transgender children. These films, though responding to the most pressing issues facing queer people 30 years ago, still felt relevant to me when I watched them. The Living End’s anarchy and anger and Swoon’s disquieting dialogue with history are both emotionally potent, intellectually honest cinematic approaches to depicting queer lives under attack, whether in 1992 or 2022.

Even with the increase in volume of queer films in mainstream filmmaking, I find that perspectives like Kalin’s and Araki’s are underrepresented, which can at least partially be attributed to the difficulties of independent filmmaking and the limits of queer narratives that corporations will bankroll. The Living End and Swoon are powerful films because they are both uncompromising, singular aesthetic visions and urgent responses to the oppression of queer communities. In her conclusion to New Queer Cinema: Director’s Cut, written during the Obama administration, B. Ruby Rich wrote “Yes, I’m happy to have more rights, but oh how I miss the outlawry of the old days.” With the rights and safety of queer people still threatened, it may be time for cinematic “outlawry” to make a return.