The boy who would one day become Lee Child was eleven years old when the light dawned. He was on the number 16 bus, heading home from King Edward’s School to Handsworth Wood in Birmingham and reading Ian Fleming’s Dr No. He may have been smoking—he’d found his first pack of ten Rothman’s King Size on the very same route just a few months earlier. He loved it from the first drag.

Earlier that day, he’d been reading ‘Theseus and the Minotaur’ at school. His Latin master rated the eleven-year-old Jim Grant highly: ‘Has gone from good to very good,’ read his report in Autumn 1965; then in Summer 1966: ‘Clever boy: with clever classmates would shoot ahead.’

Even on his own he was doing OK, and it struck him like an epiphany: ‘Theseus and the Minotaur’ and Dr No ‘were exactly the same story in every beat and every plot point’. The same stories were being told over and over again, and the better they were the more often they were told, and the more often people wanted to hear them and the more popular they became. Increase of appetite grows by what it feeds on. ‘It was the study of Latin poetry that taught me all I needed to know about genre writing,’ he would tell an assembly of academics at the Graduate Center on New York’s Fifth Avenue more than fifty years later. Together with, he might have added, a healthy dollop of James Bond.

In 2010 the author of the bestselling Jack Reacher series wrote an essay on Theseus for Thrillers: 100 Must Reads (ed. David Morrell and Hank Wagner), laying bare the prototype:

I first read this tale, in Latin, as a schoolboy. There was something about the story elements that nagged at me. I tried to reduce the specifics to generalities and arrived at a basic shape: Two superpowers in an uneasy standoff; a young man of rank acting alone and shouldering personal responsibility for a crucial outcome; a strategic alliance with a young woman from the other side; a major role for a gadget; an underground facility; an all-powerful opponent with a grotesque sidekick; a fight to the death; an escape; the cynical abandonment of the temporary female ally; the return home to a welcome that was partly grateful and partly scandalised.

Article continues after advertisement

My own Eureka moment came when I re-read The Tempest. Unbearably pretentious—I could hear Child’s judgement ringing in my ears. But I couldn’t really agree. This wasn’t a Bloomian question of canon or hierarchy; only a time traveller from the 2400s can say whether or not we are still reading Reacher in four centuries’ time. But we routinely tout the universality of Shakespeare. We marvel at how his language has shaped and permeates ours, and how it continues to do so. If this means anything, then it must be that his writing always already inhabits the writing of others, as do the Greek myths—and not just some select others, an intellectual elite approved by the arbiters of taste, but embracing all humankind equally. Shakespeare spoke to the rude mechanicals and the groundlings as much as the court, just as Child addresses the professionals at the centre of the literary universe as much as the one-book-a-year consumers that in his preferred analogy he typically locates on the outer rings of Saturn.

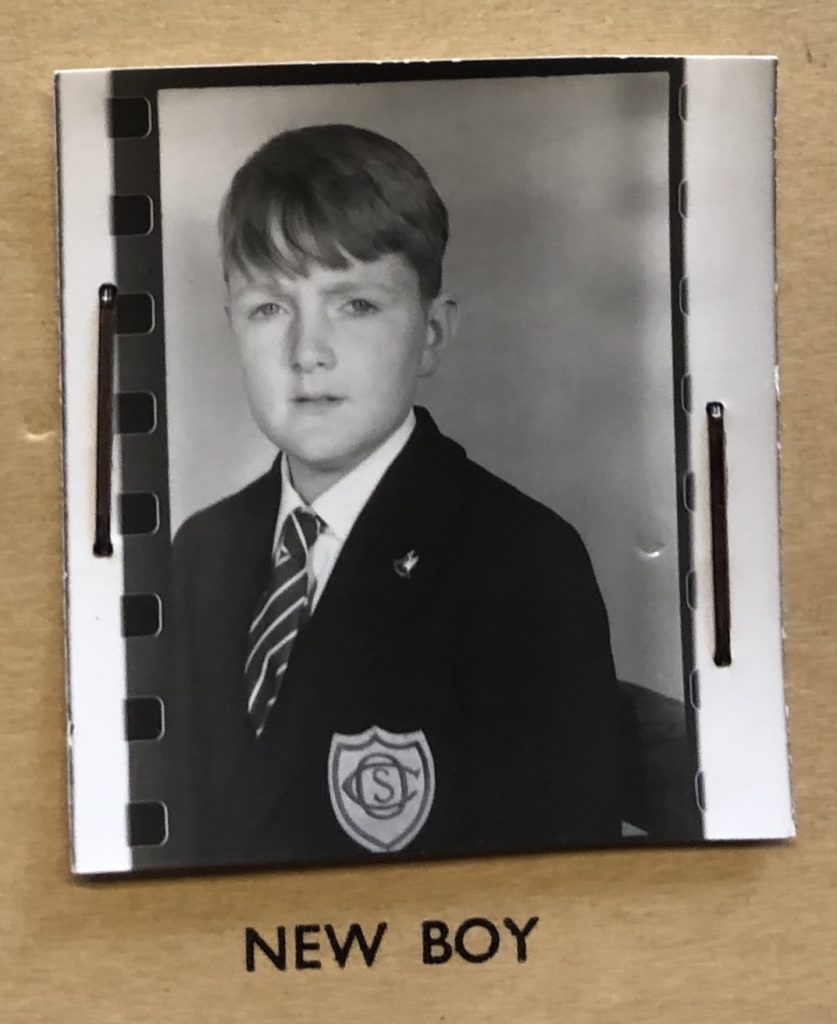

Jim Grant, aged 10, shortly after he first discovered Shakespeare (King Edward’s School archive).

Jim Grant, aged 10, shortly after he first discovered Shakespeare (King Edward’s School archive).

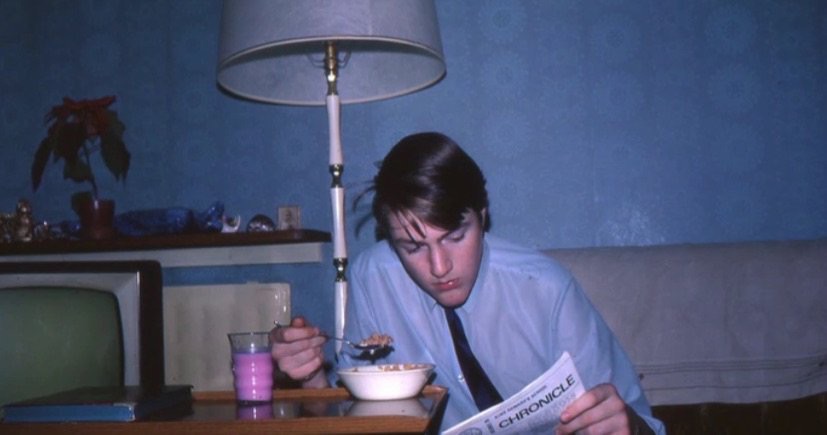

Naturally, having delved into the dark backward and abysm of time to write Lee Child’s biography and full knowing his undying love for the ‘sheer incandescent beauty of Shakespeare’s verse’, there was an element of confirmation bias in my perception of a bond between these disparate writers. Both are men of Warwickshire, and both were educated by the King Edward’s Foundation of grammar schools. Coventry, the city of Jim Grant’s birth, features prominently in Henry IV, Part 1, and just as the teenage Shakespeare would regularly walk there from Stratford-upon-Avon to watch the mystery plays, so too would Jim—a fan since the age of nine, when his father took him to see Henry IV, Part 2—catch the bus to Stratford to seek out the latest production by the Royal Shakespeare Company. As a teenager he interned there, and in 1970, on the cusp of Sixth Form, was backstage when Ian Richardson and Ben Kingsley played Prospero and Ariel, and Peter Brook first staged his seismic Dream. In 1973 he did sound and lighting for the Brook-inspired school production of The Tempest and at Sheffield University, where he spent four years in the Drama Studio while ostensibly studying Law, took as one of his early aliases ‘Richard Strange’, drawn directly from the song in which Ariel leads the distraught Ferdinand to believe that his father, Alonso, lies full fathom five beneath the ocean waves, transformed into something ‘rich and strange’ with bones of coral made and pearls that were his eyes. The programme notes for Ibsen’s A Doll’s House record that design was by Jim Grant and publicity by Richard Strange; Grant received a rave review for his stagecraft in the Sheffield Evening Telegraph.

But as always, too, there were echoes of Jorge Luis Borges (who once posited that every man who recites a line of William Shakespeare is William Shakespeare), specifically, his essay ‘Kafka and his Precursors’, in which he finds intimations of Kafka in Zeno, Han Yu, Kierkegaard, Léon Bloy, Lord Dunsany and Robert Browning, and argues that every writer creates his own precursors, colouring our readings of the past as much as the future: ‘Kafka’s idiosyncrasy is present in each of these writings […], but if Kafka had not written, we would not perceive it; that is to say, it would not exist.’ In the atemporal space of literature, Shakespeare and Child exist side by side, just as they do—for example—in the mind of Shakespeare scholar and Child aficionada, Emma Smith.

It was Smith, in her brilliantly lucid This is Shakespeare (based on her lectures at Oxford University) who focused my mind on the less superficial signs of kinship. Reacher fans know he is a throwback: stubbornly analogue, closer in spirit to Plato’s cave than the Information Age. The same is true of his creator, who even now favours Filofax over smartphone. And as a writer, it seems to me, Child is broadly driven by an early modern aesthetic.

When asked to account for the popularity of his books, Child most often concludes that the satisfactory resolution of conflict Reacher both promises and delivers is compensation and consolation for our otherwise inescapable real-life frustrations. Sadly, that satisfaction is fleeting and the insubstantial pageant too soon faded: the reader, like Ferdinand, might choose to dwell forever in the paradise of fiction; like Caliban when waked, he would cry to dream again. It follows that a Reacher story, like a Shakespeare tragedy, is immune to the spoiler, a concept Child dismisses with disdain: we all know how such stories are going to end, and knowing how they end is intrinsic to our delight in reading them. Picking up a Reacher book should be like ‘pulling on an old sweater’; fans should feel ‘welcomed and comfortable when they come into the book’. In her discussion of Shakespearean tragedy, Smith traces this aesthetic to ‘a humanist education system suspicious of novelty, sometimes judging invention or fiction as morally compromised because untrue’ (an anxiety Child movingly explores in a 2016 essay for the New Yorker, ‘The Frightening Power of Fiction’), which taught ‘generations of playwrights and poets that translating, reworking and rewriting existing texts was the sign of the artist’. The pleasure of reading, Smith writes, ‘was not in the surprise and fulfilment of seeing how things turned out in an uncertain plot, but rather in enjoying the variations on an established theme’, a formal expression of the view also held by Child’s father, John Grant, that what he looked for in ‘a good book’ was for it to be ‘the same but different’. Smith cites Jean Anouilh’s definition of tragedy as ‘restful’—on the face of it surprising, but on reflection not so at all. With tragedy, as with a Reacher story, if for different reasons, there is ‘no need to do anything. It does itself. Like clockwork set going since the beginning of time.’ Child frequently and cogently argued—not least in his 2019 non-fiction monograph The Hero—that the thriller was the original form of fiction, conceived to inspire, empower and embolden, and thereby crucially enhancing the survival odds of Homo sapiens as a species.

Smith brought other parallels to my attention, too. Though most would automatically oppose Shakespeare’s lush Elizabethan verse to Child’s spare Camusian prose, there was no denying the supererogatory detail of many of the latter’s descriptions, be they of weapons, combat, landscape or weather. And in the same way that the politically astute Shakespeare deftly avoids the partisan, allowing his plays to be ‘co-opted by different agendas in different ages’, so too the classically educated Child, likewise well-versed in argument in utramque partem, and similarly aspiring to attract the biggest possible audience, is appropriated with equal fervour by both left- and right-wing readers, all of whom see Reacher championing whichever cause is closest to their hearts, and all of whom the author hopes to subtly challenge. The larger-than-life Reacher, of monstrous dimensions, is a mythic character operating in a realist environment. His unreality is due in part to his prodigious powers of action and deduction, but also (in direct antithesis to Hamlet) his lack of explicit interiority, reminiscent of the principle of psychomania popular in medieval theatre, where elements of a single complex self are exteriorised across multiple characters—accounting for the sometimes disconcerting tendency of Reacher’s allies and accomplices, even his enemies and opponents, not merely to see the world through his eyes but to adopt his voice and mannerisms. Much is made of Reacher’s size as an unstoppable force, the invincible agent of retribution, crucial to the execution of plot. But it’s also the most obvious marker of his mythological status: he is so gargantuan a figure that he contains all others within him. The same is true of the writers themselves (there are many ways in which Reacher acts as a writer), and Prospero speaks for both Child and Shakespeare when, in contemplating Caliban, he confesses: ‘this thing of darkness I / Acknowledge mine’.

Jim Grant at home in Birmingham, aged 17, when he was volunteering as a sound and lighting technician both at school and at the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon (family photo).

Jim Grant at home in Birmingham, aged 17, when he was volunteering as a sound and lighting technician both at school and at the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon (family photo).

Like any writer, Prospero conjures a world—‘The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, / The solemn temples, the great globe itself’—out of the magic of his imagination and casts a spell over his audience, who for the space of a few hours inhabit that world and dance to his tune. Like any writer, he has power of life and death over his characters: ‘Spirits, which by mine art / I have from their confines called to enact / My present fancies.’ Or, as Child once put it: ‘I am the only person Reacher is afraid of.’ ‘The story proceeds based on the teller’s aims and the reader’s needs,’ he writes in The Hero, and: ‘The entire purpose of story is to manipulate.’ But the affinity runs deeper (starting with the shared love of books and the powerful association of words with music)—because ‘Lee Child’, like Prospero, is a fictional character.

The immediate, pressing, and entirely practical purpose for the invention of the (larger-than-life) ‘Lee Child’ was for Jim Grant to earn enough money to put food on the table for his wife and daughter, much as it was for Shakespeare. But the existential motivation ‘For raising this sea-storm’ allies Child more intimately to Prospero: revenge. Both treachery and its bedfellow, vengeance, are obsessively nursed and rehearsed, within a single spell or play in one case, and across a series of twenty-four novels in the other. In this aspect The Tempest reads like an allegory of Jim Grant’s second-act career from conception to retirement. The sense of grievance that fuels ‘the right Duke of Milan’, ousted by usurper (and brother) Antonio—amplified in the play by the plotting of Antonio and Sebastian against Alonso, and of Stephano, Trinculo and Caliban against Prospero himself—is identical to that which defines Lee Child, born out of betrayal by his beloved Granada Television, taken over and dismantled in the early 1990s by greedy upstart executives. Chief Morrison in Killing Floor, Julia Lamar in The Visitor, Colonel Willard in The Enemy, and Allen Lamaison in Bad Luck and Trouble are thinly veiled proxies for his old Granada foes, getting their just desserts in fiction in a way they never would in (ever disappointing) real life. Reacher, the novelist’s Ariel-cum-Caliban (via the wild man of the forest)—himself downsized from the army, with his own Ariel in the haptephobic Sergeant Neagley, reading his mind and anticipating his commands—systematically and inexorably catches up with the wrong-doers, and dispatches them over and over and over again (they are not given the chance to be redeemed by repentance like Alonso). Prospero, one-time ‘prince of power’, the victim of foul play, reinvents himself as all-powerful magician and king of the island; Jim Grant, one-time ‘word of God’ in his role as transmission controller, reinvents himself as undisputed king of thriller writers.

A majority of Reacher books take the form of a road trip; they all, to a greater or lesser extent, reprise The Odyssey. And the prolonged pursuit of revenge is not the only manifestation of the quest narrative in The Tempest. Alonso and Ferdinand, each believing the other to be ‘mudded’ in the ooze, nevertheless traverse the island in vain hope of finding each other. They seek freedom from the torment of guilt and grief, just as Prospero seeks freedom from exile, and Ariel and Caliban crave freedom from colonial bondage. For Reacher/Child, liberty is the upside of expulsion from the highly regimented structures of the 110th MP/Granada Television. But both the nagging sense of betrayal (by parents and school mates) and the longing to escape (from family and grey, postwar Britain) go back much further in Child’s life, to the root of who he is. In a 60-page essay on Anglo-Saxon England that the young Jim Grant successfully submitted for the Medieval History Prize at A Level he declares his support for the oppressed ‘little guy’, his contempt for the bloated ‘big guy’, and his empathy for the freed slave, dwelling on the act of manumission that took place at a crossroads, leaving the once bound man to wander at will, his own master at last, just like the newly minted hobo of Killing Floor and its prequel, The Affair. We may never hear Reacher chanting ‘Freedom, high-day, freedom’ or ‘Merrily, merrily shall I live now’ while he waits patiently for a ride at the cloverleaf, but we soon learn that it is freedom he cherishes above all else; that freedom outweighs even his deeply suppressed fear of loneliness.

The essence of Lee Child’s early modern aesthetic is his respect, even reverence, for craftsmanship, a legacy, he would argue, of his sociological origins. In Shakespeare’s day, Warwickshire, with Coventry as its principal city, was the headquarters of the wool and textiles trade. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with the creation of a magnificent Grand Central-style canal system, it evolved into one of England’s foremost industrial counties; the population of Birmingham grew from less than 100,000 to more than three-quarters of a million, with seventy-five per cent of people employed in manufacturing. In the twentieth it became the centre of the motor industry. The city Jim Grant grew up in was renowned for its skilled metalworkers. On Saturday mornings he would wander down the road to visit his mate David Harris, whose father made beautiful things out of metal in his bare-earth workshop—exquisite cruet sets in finely wrought silver for Cunard’s original Queen Mary, and fake silver coins commissioned by the Greek government to facilitate a good archaeological experience for tourists on Knossos (home of the Minotaur).

Child saw his books as the product of honest craft, and as such it was imperative they be made well and do the job they were designed to do, so the consumer would have confidence in his handiwork and come back for more, and then more again. Like the wheelwright made wheels, the cartwright carts, and the playwright plays, he, the bookwright, made books. He was a book writer, plain and simple. It was not the analogy with master craftsman Shakespeare that was unbearably pretentious, but rather the concept of the ‘author’—worse still, auteur—with its attendant romantic notions of divine inspiration.

Shakespeare achieved star status in his lifetime, and in 1597 bought the second-largest house in Stratford. Lee Child was similarly successful. But however wealthy he became, selling over one hundred million books in more than forty languages across the globe and cashing in on the fringe benefits of two Hollywood movies, he never lost sight of the original motivation to put food on the table; the responsibility of breadwinner was programmed into his middle-class DNA. And it was that obligation to his tribe, as well as to the fans that had made his fortune (hopelessly addicted to the formula of a Reacher novel a year) that in 2020 compelled him, when he reached retirement age, to hand over his kingdom to his younger brother, also a thriller writer and seemingly destined to inherit the franchise. Child’s daughter Ruth was already provided for; now Andrew Grant and all his descendants would be too.

Like Prospero, his lust for vengeance assuaged and his material goals exceeded, Lee Child could finally lay down the burden of creation and retreat to Milan, or in his case, Wyoming. He was happy to put aside his staff, but no way would he drown any books. He was tired, he claimed; he felt old, he said; he no longer believed, as he had done a few years earlier, that he could be parachuted into any new situation and within days be the master of it. It was time to relinquish the loftier magic for the resumption of mortal humanity.

At the end of The Tempest Prospero addresses his audience in an epilogue, the conventional appeal for applause reminding us that—like Lee Child—Shakespeare was first and foremost an entertainer:

Now my charms are all o’erthrown,

Article continues after advertisementAnd what strength I have’s mine own,

Which is most faint. Now t’is true

I must be here confined by you,

Or sent to Naples. Let me not,

Since I have my dukedom got

And pardoned the deceiver, dwell

In this bare island by your spell;

But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands.

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant,

And my ending is despair

Unless I be relieved by prayer,

Which pierces so, that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardoned be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

‘I’ve told twenty-four decent stories in the course of my life,’ Child told me in early 2019. In January 2020 he sent me his own epilogue to my biography, neatly prepackaged in quotation marks:

‘As a final rumination, lately I have been thinking along these lines, which might be a kind of epitaph:

“People ask, am I happy now I have retired? The truth is, I retired because now I’m happy. The times I grew up in, and the place, and my family, all left me with an implacable horror of being mediocre. Finally, after all these years, I have grown to accept I escaped that fate.”’

But he’d already put his thoughts in Abby’s mouth towards the end of the last of the sole-authored books in the series, Blue Moon:

‘Seems to me I have a choice of two things. Either a good memory with a beginning and an end, or a long slow fizzle, where I get tired of motels and hitchhiking and walking. I choose the memory. Of a successful experiment. Much rarer than you think. We did good, Reacher.’

___________________________________

Heather Martin’s authorised biography of Lee Child, The Reacher Guy, is published by Constable at Little, Brown in the UK, and in the US by Pegasus Books.