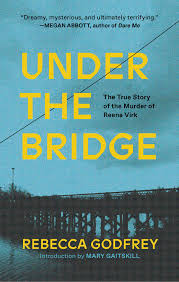

When Rebecca Godfrey’s Under the Bridge was first published, in 2005, the world wasn’t quite ready. A thoughtful and provocative excavation of a hideous act, Under The Bridge didn’t fit easily into the true crime genre, a category then still considered to be lurid. Under the Bridge may be more at home in today’s pantheon of “prestige” true crime content, but that doesn’t make it any less shocking. More than twenty years after it happened, the murder of 14-year-old Reena Virk is still heartbreaking and harrowing. Virk’s killers were teenagers, most of them girls, and Godfrey never makes the mistake of underestimating them. Each player in the tragedy is depicted with almost Tolstoyan precision. True Crime often features young women as victims, but in Under The Bridge, they are perpetrators, too, and Godfrey is one of the foremost chroniclers of female rage. The first time I read Under the Bridge, I was swept along by the story. The second time I read it, I was struck by the beauty of Godfrey’s prose and her unusual, almost surreal imagery. Mostly, however, I was impressed by the enormous empathy with which she writes about her subjects. Where other writers would look away in fear, Godfrey looks closer.

I’ll start with the obvious question: what was the original genesis of this book? What drew you to the case?

I saw the headline in November, 1997, in The New York Times, “Grisly Killing of Girl, 14, Startles A Small Town in British Columbia.” At the time, I was living in downtown New York, and “the small town” was Victoria, where I’d grown up, so there was a personal connection to the story. Eight teenagers had been arrested, seven girls. In the article, a friend of the girls said, “They were not a gang. They were a group of friends hanging out and things happened.” She said the motive was “rumors.” I was really intrigued by the evasive nature of the teenager’s answers—I wondered: What things happened? What were the rumors?

Soon after, I ended up seeing the arrested girls at the juvenile detention center in Victoria. They were each in a small cell, and they looked just like ordinary, suburban girls. The disconnect between their appearance and their alleged actions was so strong—I couldn’t stop thinking about them, thinking, “Well, what if they are innocent?”

How were you able to learn more about them?

Victoria’s a very small town, and I had a lot of connections, just from having grown up there. My friend’s dad was a social worker assigned to one of the girls; another friend’s brother worked as a guard in juvie. I began to learn more, talk to people who knew the accused teenagers and their friends, and ultimately, I talked to many of them directly.

I had absolutely no experience in crime reporting, but I could see that there was another story to be told, one that was very different than the official stories from detectives or established reporters, all of whom were older men who hadn’t spoken to the girls, and didn’t really seem to have the ability to understand their world or lives.

Your novel, The Torn Skirt, deals with many of the same concerns as Under the Bridge—teenage girls, small towns, violence and rebellion. What made you decide to write Under the Bridge as a work of nonfiction, rather than using the case as the basis for a novel? What kinds of challenges do you face as a journalist rather than a novelist? What kinds of freedoms?

In the Reena Virk case, the truth really was stranger than fiction. I couldn’t have invented a story with so much tragedy and so many compelling characters. I found I enjoyed the research aspect—going to trials, getting confidential documents, interviewing all kinds of people. I was terrified at first, but found if your interest is genuine and sustained, people respond. They want to help you get the story right.

I wasn’t taken seriously by a lot of officials; I was young and looked younger, and that actually was a great advantage. A lot of high profile reporters were stonewalled by police or lawyers, but I could get into a lot of rooms and have a lot of conversations because no one with authority was really paying attention to me or seeing me as important.

In terms of freedoms, as a novelist, I was able to use a different kind of language. Journalists are limited by the need to be “objective” and to do that they pare back the emotion or poetry. I could also play with form. I didn’t follow that procedural template of murder, arrest, investigation, trial that we are so used to from Law and Order type narratives. I really wanted to avoid that detached, clinical voice journalism or crime stories so often have, and to do so, I turned to the techniques of a novel which allowed me to write the story in a more scenic, detailed, intimate way. But I also had to stay true to the reality and facts. For example, in interrogation scenes, or trial scenes, I always used the actual dialogue. That was definitely a challenge, presenting the story in an accurate way, but also bringing some beauty and humor and insight to it.

One of the original covers of the book features a white girl with butterfly tattoo on her back. Did you feel that the way the book was marketed contrasted with the kind of story you were telling?

“We’d joke that our books looked like tampon ads. It was maddening, particularly when you’ve written a book that aims to challenge or change those attitudes about young women.”I loathed that butterfly tramp stamp (laughs). It didn’t capture any of the darkness or atmosphere of the story. It felt very Britney Spears, saccharine. Back then, there was a tendency to market women’s books, fiction or nonfiction, with these Hallmark covers, stock photos and a kind of generic, “feminine” style. It happened to many of my friends as well. We’d joke that our books looked like tampon ads. It was maddening, particularly when you’ve written a book that aims to challenge or change those attitudes about young women.

Can you tell me a little bit about the process of re-issuing the book?

In 2005, when the book came out, there wasn’t the same audience for true crime as there is now, because of Serial, How to Make a Murderer, etc. With the exception of In Cold Blood, true crime was seen as kind of déclassé, not something sophisticated or revelatory. When I was writing the book and would tell people about it at dinner parties, they would wince. They looked like they wanted to run away. That stigma has really evaporated, and there’s a hunger now for books that explore a crime, but also the social or political forces behind the crime, and the shifting stories surrounding the crime.

It was very exciting to have Mary Gaitskill write the introduction, because I’ve been very influenced by her work and her ability to get at the way women, particularly young women, struggle with and enjoy rage, desire, envy, longing. She really understood Under the Bridge in a way I don’t think I even understand it.

I wrote an afterword, which I enjoyed doing, just having the opportunity to explore what became of everyone. The two teenagers who were given life sentences for second-degree murders took very different paths after they were incarcerated. Again, I couldn’t have invented such twists and turns.

There’s something about this story, these characters, that maintains a pull on people—even twenty years later. I’m still asked to go to schools to talk, and people always want to know, “Where are they now? What happened to Syreeta and Warren?” The loss of Reena Virk still haunts—it’s almost like a Victorian or Gothic novel—this haunting doesn’t cease; it just persists in strange, almost otherworldly ways.

True crime, obviously, is going through a bit of a renaissance, and along with it is an increased appetite for all that deals with violence and murder. Do you think Under The Bridge fits into this trend?

I think it does fit into this desire to explore crime not as an act of evil, but as a mirror into our lives. Part of the “prestige” element we’re seeing is because reporters or writers aren’t looking at the stereotypical killer, the nice guy/secret psychopath, like Paul Bernardo or Ted Bundy. There’s a more nuanced look at the violence of college kids, mothers, yoga teachers—people who don’t fit the profile and thus their role in a murder is more mysterious, more in doubt. Perhaps, since we’re dealing with Trump’s cruelty, there’s a desire to see morality win out; we want to believe there can be a triumph of justice, even while understanding, goodness to be difficult or elusive. We want to know why bad things happen but not in a way that’s lurid or voyeuristic. I think it’s been a really important shift—to understand that guilt or innocence are not always clear cut, and that the official stories, of courtrooms or headlines, are often very flawed. In Under the Bridge, Kelly Ellard, the 14 year old girl accused of murder, yells at the police, “Everyone’s got a story. My story is different than theirs.” I wrote the book with that idea in mind, that every crime is composed of many, many stories.

Anya and Nadja were, for me, the most compelling figures in the book. I was astonished by their courage and their determination to do right by a girl they had never met. Can you talk about them a little more?

They were two teenage sisters in the foster care system, both very street-smart and sharp. At the time of the murder, they were living in a group home and they’d met the victim, Reena Virk there. One of the girls in the group home started boasting about the murder and how she was going to get away with it. A lot of kids heard these boasts, because the rumors of a girl being killed were rampant in the high schools.) Anya and Nadja were the first—and only—teenagers to go to the police. They acted as detectives when the real detectives didn’t take them seriously. They called Reena’s mother, confirmed that Reena was missing. They got the girl who was boasting about killing Reena to take them to the scene of the crime, and they asked her questions. “Who was with you?” “How did you move the body?” “What happened to her shoes?” Then they went back to detectives, gave them this information, and said, “Do something! Get divers to search for a body! Go arrest these girls!” The police thought the story was “far-fetched” but eventually they did begin to investigate. I really think the crime might never have been discovered if it weren’t for the two sisters. This was before social media, before email or GPS, so the killers were really able to keep the crime a secret for a surprising amount of time. To me, the sisters are the true heroes of the book.

Another character I’m completely obsessed with is Josephine, because she’s so unlike anyone I’ve encountered in life or in fiction. I don’t even really have any reference points to compare her to. How do you bring someone like that to life?

“Early on, a detective told me that when he arrested her, she asked for John Gotti’s lawyer…Her friends described her as looking like a ballerina, very delicate and classically pretty. I just thought, who is this girl?”I was obsessed with Josephine too. Early on, a detective told me that when he arrested her, she asked for John Gotti’s lawyer. He also told me she’d broken out of jail twice. Her friends described her as looking like a ballerina, very delicate and classically pretty. I just thought, who is this girl? She was really ruthless but also very loyal to her best friend. I got a hold of transcripts of her interview with the police, where they’re trying to turn her, trying to get her to tell them that her best friend was the killer, and she’s incredibly defiant. She’s only fourteen, and she’s just completely in control of the conversation. She veers between using gangster lingo, and manipulating the police—she acts the part of a teenage girl to throw them off. “We don’t talk about murder. We talk about make up and cigarettes.”

I also drew on my email correspondence with her. She was very forthright, funny, incredibly confident. Over time, she showed remorse for her role in the crime.

On my first reading of the book, I sped through it, because I was so eager to find out what happened. Re-reading it now, I’m struck by how unrelentingly sad it is. How do you pull the reader through a narrative this bleak?

I tried to have enough moments of beauty to balance out the sadness. I wanted to be honest to the experience—the loss of a young girl—while also finding these moments—the falling Russian satellite in the sky, the innocent first love of two characters, the dignity of Reena’s grandfather, the verve and sass of Anya and Nadja—which existed in the midst of a tragedy.

Are there ways in which this is a uniquely Canadian story? I found myself wondering how certain elements would have played out had the case taken place in the US—for instance, the death penalty is never a possibility for the perpetrators.

The central themes—envy, loyalty, first love—aren’t uniquely Canadian, and certainly the issue of high school violence is more prevalent—and fatal—in the US. But you’re right, the legal system in Canada is less punitive. One of the killers was able to participate in Restorative Justice programs, and meet with Reena Virk’s parents. I don’t know if that forgiveness and redemption could have happened with an incarcerated teen in the US.

What do you hope readers will take from the reissue that they might have missed in the original printing?

I do hope that the book will find a new audience, especially among young women who were too young to hear of the Reena Virk murder in 1997. There’s been some change in how popular culture or literature portrays young women and violence—in say, The Hunger Games or Sharp Objects. But, I still find it astonishing that so many beloved shows still only portray young women as victims. Watching True Detective, Twin Peaks, House of Cards—it’s just one pretty young brunette after another getting tortured, slashed, pushed in front of a train. It’s almost absurd. And these shows are really interested in the struggles of the male detectives, politicians, bikers, or whatever. The death of the girl is just an inciting event for their journey. In my book, the young women plan violence, they enact it, they suffer from it, and they survive it. I think that’s a more complicated, resonant story than what we so often see.