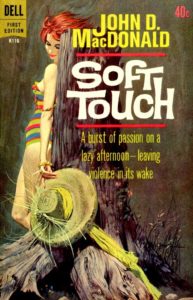

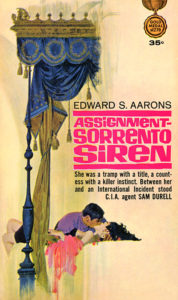

It’s possible that you don’t immediately recognize the name Robert McGinnis. But if you are even remotely interested in vintage crime, mystery, and thriller novels, you’ve certainly spotted his artwork. After all, he’s spent the last 60 years painting exceptional covers for those sorts of paperback yarns, most of them by still-familiar authors (Erle Stanley Gardner, Brett Halliday, Ruth Rendell, John D. MacDonald), though others came from writers whose popularity has since waned considerably (Carter Brown, Edward S. Aarons, Phoebe Atwood Taylor, Harold Q. Masur, and the like).

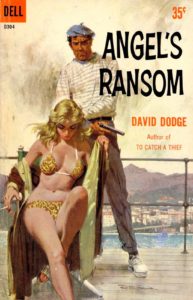

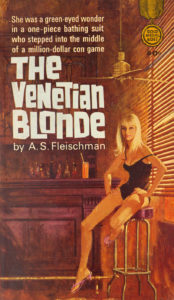

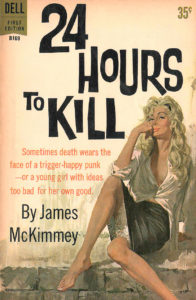

Over the course of his career, McGinnis—set to celebrate his 93rd birthday this coming Sunday—has produced more than 1,000 unique paintings employed on American paperback book covers. His works are distinguished by their precise use of color, the artist’s preference for portraiture over depicting story scenes, and especially the lithe and luscious women who are so often the focal point of his canvases. Women whom Vanity Fair once described as “a mix of Greek goddess and man-eating Ursula Andress.”

“Yes, there have been other painters who painted beautiful women—but there’s nothing like a McGinnis woman,” raves Charles Ardai, the editor at New York publishing house Hard Case Crime, which specializes in vintage-style paperback fronts and has made plentiful use of this artist’s output over the last decade and a half. “Leggy, serene, aloof, unruffled, coiled, and deadly or enigmatic and sensuous, Bob’s women are like otherworldly creatures, breathtaking and perfect.”

However, the appeal of McGinnis’s female subjects goes beyond their conspicuous corporeal attributes, insists Art Scott, who co-authored—with the painter himself—a handsome 2014 book, The Art of Robert E. McGinnis. “To me,” Scott says, “his exceptional talent for depicting physical beauty and sensuality is secondary to his gift for imbuing his women with personality: intelligence, competence, spunkiness, danger—as called for in their portrayal in the text. Other top paperback artists had this gift as well, but pre-McGinnis especially, the Calendar Girl/Starlet (or Calendar Girl/Starlet Menaced by Bad Guy) look and pose was what was usually on the covers.”

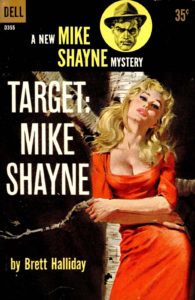

The case could well be made that McGinnis, along with contemporary commercial illustrators such as Mitchell Hooks, Ron Lesser, Robert Maguire, and Harry Bennett, was instrumental in raising the profile (and sales) of crime and detective fiction during the latter half of the 20th century. “His work was highly influential, both in the sense that a lot of other painters of paperback covers tried to imitate the McGinnis ‘look’ and in the sense that his beautiful covers got a lot of readers to pick up books they might not otherwise have tried,” explains Ardai. “I know my father bought Brett Halliday’s Mike Shayne novels at least as much for the covers as for the stories inside, and I’d much rather look at a Carter Brown cover than read a Carter Brown novel any day.”

McGinnis has deployed his genius widely over the years. He’s crafted fronts not only for works of crime and spy fiction, but also for historical and Gothic romance novels. He has contributed to slick magazines and developed iconic posters for such Hollywood flicks as Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Barbarella, The Odd Couple, Cotton Comes to Harlem, and Sean Connery’s 1967 James Bond movie, You Only Live Twice. And he’s exercised “pure self-expression” through an assortment of gallery pieces, primarily portraits of women, rural landscapes, and Old West scenery. His colleagues at the Society of Illustrators recognized McGinnis’s expertise and prolificacy in 1993, when they elected him to the Illustrators’ Hall of Fame, an honor first bestowed on Norman Rockwell in 1958.

Yet this “pop culture Rembrandt” (as he was dubbed by a magazine serving his current hometown of Greenwich, Connecticut) got his start in the book-cover biz illustrating crime novels. And more than half a century later, he’s still influencing that field.

***

Born on February 3, 1926, and reared in Wyoming, Ohio, a farm country town not far from Cincinnati, McGinnis showed early artistic leanings. “He wanted to draw his favorite comic strip character, Popeye,” Scott writes in The Art of Robert E. McGinnis, “and his father, himself a talented artist, took his hand and guided it in drawing the cartoon sailor.” With his mother’s encouragement, McGinnis took classes at the Cincinnati Art Museum, and after high school he apprenticed as an animator at Walt Disney Studios.

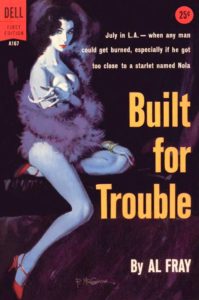

He served with the U.S. Merchant Marine during World War II, and subsequently studied and played football at Ohio State University. McGinnis had once thought of going into agriculture, but in 1953 he and his former college sweetheart, Ferne Mitchell (whom he’d married in 1948), relocated to the New York City area, where he instead took up commercial artistry and in 1956 started illustrating fronts for magazines such as True Detective and Master Detective. Through his contact with the then up-and-coming Mitchell Hooks, McGinnis won his earliest assignments painting covers for crime novels (at $200 apiece). The 1958 Dell Books release So Young, So Cold, So Fair, by John Creasey, marked his debut as a paperback artist; within two months more, his work was again spotted in bookstores and on spinner racks, this time introducing Built for Trouble, by Al Fray. Scott cites the 1959 cover of Gil Brewer’s The Red Scarf, which the painter sold to publisher Fawcett Crest, as “one of the earliest examples of the fully realized ‘McGinnis Woman.’”

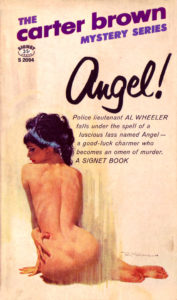

In addition to boasting signal flair with a brush, McGinnis was known for going out of his way to please art directors, often submitting multiple sketched proposals for a cover, rather than just one. Frank Kozelek, who worked with him at Signet, publisher of the Carter Brown series in the 1960s, recalled in an essay for 2001’s The Paperback Covers of Robert McGinnis (compiled by Art Scott and Dr. Wallace Maynard) that “This was Bob’s hallmark throughout my working relationship with him. He always wanted to give you his best effort to choose from. He was always concerned with your reaction to his work and always ready to do more on a project if you weren’t totally happy with either a sketch or a finished painting. I don’t think I have ever met an artist with less apparent ego—though his work could have supported a very healthy one.”

McGinnis’s first big break came when he was hired to illustrate Dell’s line of Michael Shayne mysteries. They were built around a rangy, redheaded Miami private investigator and were penned originally by Davis Dresser, a Chicago-born, Texas-bred ex-civil engineer who sported an eye patch (the consequence of a barbed-wire mishap during his boyhood) and wrote under the pseudonym Brett Halliday. Scott notes that between 1958 and 1968, McGinnis created for the Shayne books 86 portraits of women—most of them pictured alone—beginning with The Private Practice of Michael Shayne.

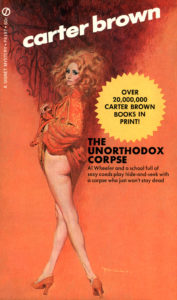

In 1961 the artist scored an even bigger commission, this time from Signet, which led to his fashioning 100 covers for a best-selling succession of short novels concocted by a English-born Australian writer named Alan Geoffrey Yates, better recognized by his nom de plume, Carter Brown. Those books were filled with provocative plots and racy dialogue, and served up several continuing leads, among them Hollywood gumshoe Rick Holman (“savior of blackmailed film starlets”), New York City-based detective Danny Boyd, hard-drinking Southern California homicide cop Al Wheeler, and “torrid blonde private eye” Mavis Seidlitz. It depended largely on those revolving protagonists to differentiate the Brown books from one another; the plots themselves might have worked fine with any of Yates’s sleuths at the helm.

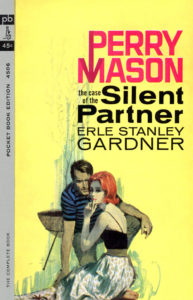

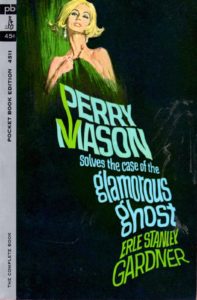

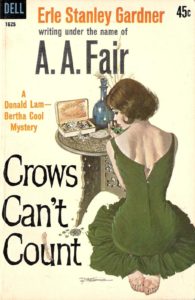

Only when compared with those two projects do McGinnis’s daunting labors on behalf of Pocket Books’ array of Perry Mason novels pale. He painted only 30 fronts, during the early ’60s, for Gardner’s twisty and often dramatic novels about a phenomenally successful Los Angeles defense attorney. Beyond those, however, McGinnis conceived a variety of covers for another, smaller, more light-hearted Gardner mystery series, this one written under the pen name A.A. Fair and focusing on a mismatched pair of L.A. shamuses: Donald Lam, a brave and “brainy little runt,” who, after losing his license to practice law, was enlisted as principal operative for B. Cool—Confidential Investigations; and Bertha Cool, the corpulent, bad-tempered, and 60-something proprietor of that agency, who was prone toward uttering outlandish exclamations such as “Kipper me for a herring!” and “Peel me for a grape!”

By the mid-1960s, McGinnis’s liberated pop culture aesthetic was much in vogue, and crime-fiction publishers recognized the value of his most basic design formula: gorgeous women on simple backgrounds, with minimal type and occasionally a series hero or cameo portrait of one. “The women,” Scott asserts, “were easier to remember than titles, and the customer’s ‘I don’t think I’ve seen her before’ sold the book.”

McGinnis soon put his stamp on four other lines of novels. He delivered themed images for 25 tales by New York author Kendell Foster Crossen. The majority of those graced books Crossen had devised under his alias M.E. Chaber, featuring a globetrotting insurance investigator named Milo March. The covers found March (a dead ringer for actor James Coburn, in McGinnis’s imagination) coupled with a winsome, often insufficiently attired young woman (or two, as in a single instance). A Lonely Walk (1970) and As Old as Cain (1971)—the latter of which finds the snoop, libation in hand, standing behind a seated blonde who looks strikingly like Goldie Hawn—are two excellent examples of the breed.

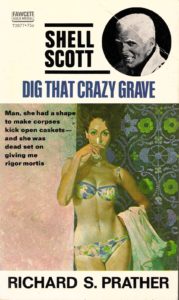

In addition, this artist applied his fine hand to 16 of Richard S. Prather’s Shell Scott P.I. novels; almost two dozen Edward S. Aarons stories starring Cajun CIA agent Sam Durrell, all of which included “Assignment” in their titles and sent the protagonist away to exotic foreign locales; and more than 40 John D. MacDonald books, both his outings for Florida “salvage consultant” Travis McGee and his standalone works.

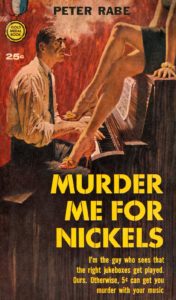

“One thing I’ve noticed on the crime novels especially,” says Scott, “is how brightly lit most of his images are—rather unexpected, given how many of those books fall into the ‘noir’ genre. Together with his clean lines and uncluttered layouts, this made his images pop and easy to ‘read.’ [Peter Rabe’s 1960 novel] Murder Me for Nickels certainly fits the noir look, but not many others. Robert Maguire, on the other hand, never missed a chance to work the light-and-shade angle and did it brilliantly. McGinnis showed off his artistry with the dark and shadowy in the Gothics.” (Examples of his Gothic paintings can be enjoyed here.)

Scott observes that McGinnis “also likes the dramatic use of bold one-color backgrounds: e.g., orange—Donald Mackenzie’s Moment of Danger [1959], Carter Brown’s The Unorthodox Corpse [1970]—and blue, almost monochrome, as on Ed McBain’s The Con Man [1962].”

McGinnis has turned out so many eye-catching paperback covers over the last six decades, that choosing the “best” is well-nigh impossible. Scott is willing to identify a few of his personal favorites. Others, though, might favor James McKimmey’s The Wrong Ones (1961). Or perhaps the 1961 Steve Bentley thriller Angel Eyes, plotted by future Watergate scandal co-conspirator E. Howard Hunt under one of his many pseudonyms, Robert Dietrich, and part of a set employing what Scott calls McGinnis’s one-shoe-off gimmick. Many critics would give high marks to Model for Murder (1959), the second of Robert Kyle’s P.I. Ben Gates novels, as well as to the McGinnis façades for Donald E. Westlake’s Parker novels, which he brought to print under the byline “Richard Stark.” And what about such standouts as Stanley Ellin’s The Eighth Circle (1958), Day Keene’s Too Hot to Hold (1959), Dan Cushman’s Opium Flower (1963), Jim Thompson’s Pop. 1280 (1964), and Peter O’Donnell’s Modesty Blaise (1966)? Or the Hard Case Crime novels McGinnis has most recently been enhancing?

The once-significant market for original paperback artistry pretty much dried up by the 1980s, as cheaper photographs replaced painted covers. Yet in 2004, Charles Ardai asked the then 78-year-old McGinnis to bring his “old-school, retro look” to Hard Case Crime. Since then, McGinnis’s art has appeared on 25 Hard Case titles. The first was Little Girl Lost, a novel composed by Ardai as “Richard Aleas,” with later illustrations being picked up for reprints or new yarns by Lawrence Block, Stephen King, Russell Atwood, Ed McBain, and others.

One of the authors who’s benefited most from McGinnis’s association with Hard Case Crime is Max Allan Collins, who has so far seen nine of his novels fronted by “McGinnis Women.” “When I started out, in the early ’70s,” Collins recalls, “I was at the tail end of the era I loved—Rex Stout and Agatha Christie and [Mickey] Spillane and McBain were all still publishing, and a bunch more. But I was getting lousy photo covers and felt the era of the great pulp-style book covers was over.”

Then, shortly after the 20th century slipped into the 21st, Ardai asked Collins if he’d be interested in reviving a character he’d last written about in 1987: the “remorseless hit man” known as Quarry. Collins said he’d do it—but only if Ardai enlisted McGinnis as the cover artist. The result was The Last Quarry (2006). It was followed by The Consummata, a sequel to Spillane’s 1967 Morgan the Raider novel, The Delta Factor, which had been left half-finished when Spillane died in 2006; Collins completed the book and saw it published by Hard Case in 2011, with another McGinnis front.

Four years later, as pay cable TV network Cinemax was preparing to launch a series based on Collins’s Quarry stories, Ardai decided to reprint all of the original Quarry novels, beginning with 1976’s Quarry (aka The Broker). Trouble was, that opportunity came on quickly, and the challenge of commissioning five brand-new cover illustrations all at once, with short deadlines, was formidable. Collins suggested they approach McGinnis, to see whether he had any extra paintings lying about his studio, in need of homes. They got lucky, as Collins explains: “Bob had five unused paintings, in just the right style for my books and Hard Case Crime. I’m not positive, but I think those may have been the only unused paintings in the genre that he had available.”

Back when Robert McGinnis began working on paperback fronts, a lot of other artists eschewed the field, thinking it second-rate. However, he’s made a prominent name for himself with his exacting eye and the sophisticated temptresses who spill from his brushes. Ardai has already slated another McGinnis piece to appear on The Triumph of the Spider Monkey, a 1976 Joyce Carol Oates novella that Hard Case will reissue in July. “We have several more paintings from Bob in inventory,” the editor explains. “I can’t tell you too much about which authors’ work they’ll be for, except in one case: one of them will be a cover for an upcoming graphic novel I’m writing myself, called Gun Honey.”

A couple of years ago, McGinnis told an interviewer, “I don’t know what I would do if I ever stopped painting.” At the rate he’s going these days, and with any luck, he may never have to find out.