I have spent the last ten years writing Historical Romance set in the Old West, Regency and Victorian England, and the Highlands. As a History major in college, it suited me just fine to write about the time periods I studied in school, so when I penned my first romance novel, it was, of course, set in the late 1800s on the Oregon Trail.

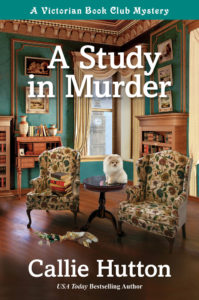

Two years ago, I decided to try my hand at writing a cozy mystery, and since I am most comfortable writing historical novels, of course I set A Study in Murder in Sherlock Holmes’ era.

Aside from my love of history, there seems to be something sinister about that time period in England. Sherlock Holmes, Charles Dickens, Jack the Ripper. As I wrote, I imagined dark, dreary settings with rain continuously falling and the sound of horse’s hooves clopping on cobblestone streets.

I have two shelves full of historical research books, and nine binders of information I’ve printed off the internet about the time periods I write in. However, very little of my years of research covered solving crimes without the help of modern day forensics and methods of communications.

One thing in my favor, of course, was cozy mysteries generally do not rely as heavily on forensics as say thrillers (James Patterson) or mysteries (Stephen King). After all, Miss Marple had no blood splatter analysts on hand. She solved her crimes by using common sense, a knowledge of how human nature worked no matter where or when, and her ability to get people to confide in her over a cozy visit. Tea, anyone?

I spent a great deal of time googling various crime solving methods and studying timelines of when things were invented and commonly used. While fingerprinting was known, it wasn’t until 1892 that an Argentinean Police Commodore, Juan Vucetich, retrieved fingerprints off a door post to identify a murderer.

A Study in Murder, set in 1891, would have no such resources available to the police, who weren’t doing such a good job of finding the correct killer, anyway. Isn’t that why we have amateur sleuths?

Aside from the usual lack of scientific help, my sleuths had no cell phones, internet, cars, airplanes, and other modern-day conveniences.

The historical fiction writer brings more than a story to her readers. He or she introduces a time and place not all readers might be familiar with. A different way of dressing, speaking, or conducting one’s life. There was no jumping into a car to make a quick getaway from a dangerous situation or pulling out a Glock to shoot at the bad guy.

Things moved slower in the past. Travel took a long time, and notes had to be sent back and forth between houses in lieu of picking up a phone. One also had to be aware of the so-called sensibilities of women at the time, although my heroine is a murder mystery writer, so she doesn’t shy away from the thought of visiting a morgue to identify a water-logged body with her co-conspirator. (Yes, she faints.)

Good manners were expected. One did not ask personal questions or offer broad insults. Men ruled the day, so women had to be more circumspect in their dealings with uncomfortable inquiries. Questions had to be asked in such a way that it seemed like normal conversation.

Again, the habit of tea came into play quite a bit in my story. Women were wont to speak freely over a warm cup and a few biscuits (cookies to us Americans). There were also sewing groups, church, and in A Study of Murder, a book club where Amy and William gathered a lot of their information.

Injuries and gunshot wounds, in particular, did not heal as quickly as they do today, and people were confined to bed for longer periods of time when they did suffer some sort of injury.

Dress, food, communications and manners change, but alas, people do not. Just ask Miss Marple.As a history lover, I have to be careful in my books to make sure I am not writing a history book. My books are set in Bath, England—where I have visited twice—which still has a great deal of history in its streets and buildings. That helped in setting my story, but it’s far too easy for us nerds to start including information that fascinates us but might have a reader skipping pages to get back to the story.

Another thing a historical author must be aware of is anachronisms, which is where my online etymology comes in handy. Words having to do with crime, or even just with every day items can be checked there for the date a word was first in use.

Since I am an American, and my books are set in Bath, England, I must also be aware of British vs. American terms. For example, I have an excellent beta reader who lives in Bath, England who told me the difference between ‘steps’ and ‘stairs.’ To me, they were the same thing, but not to a British reader.

My intent in writing historical novels is to keep the reader interested in the story, and ‘whodunit’, but also bring the past alive. Our modern-day life can impose some strong difficulties and stressors. I’m quite sure there were plenty of difficulties in the past, as well, but my intention is to make it seem interesting and believable.

I take liberties in some respects. My characters take far more baths than I’m sure the nineteen hundred century people did. I have, on occasion, used an instrument or moved up a date of an occurrence to fit the story. I always comment in my Author’s Notes about things I’ve changed.

Since I do a lot of research, and I assume many of the people who read historical fiction do like history, I generally also leave in my Author’s Notes fascinating (at least to me) information that I uncovered in my research. From what I’ve seen, some reviewers like that.

However, contemporary mysteries and historical mysteries are basically the same. As Miss Marple said, people are alike, whether it’s in her small village of St. Mary Mead, or at a luxurious hotel in the Caribbean.

Dress, food, communications and manners change, but alas, people do not. Just ask Miss Marple.

***