Although I’d previously sat through numerous TV mystery and detective dramas, and had occasionally come across crime short stories in my classroom reading, the first novel I ever tackled in this genre was 1949’s The Moving Target, by Ross Macdonald. I was just a teenager, working in my high school library, when the assistant librarian handed me a paperback copy of Macdonald’s first Lew Archer private-eye novel, saying, “You’ll like this one.” And boy, did I ever! Reading The Moving Target marked the start of my lifelong love of crime fiction, an interest that led me to become a critic of this literary category and a frequent interviewer of authors who’ve contributed to it—including, not long before he died, Ross Macdonald himself.

I am reminded of this, because today marks the 70th anniversary of the original release of The Moving Target, according to Matthew J. Bruccoli’s authoritative 1983 bibliography of Macdonald’s works. Or should I say, Kenneth Millar’s works, because that was the novelist’s real moniker. He was born in California, but grew up in Canada before returning to the Golden State as an adult. He dreamed of penning “real” novels, but conceded it was better to “write good commercial tripe than unpublished serious stuff.” Not everyone, however, admired his nascent efforts; indeed, Raymond Chandler, the esteemed creator of Los Angeles gumshoe Philip Marlowe, derided the “pretentiousness” of phrasing in Target and questioned the depth of “natural animal emotion” behind Millar/Macdonald’s storytelling. Fortunately, others were more encouraging, notably Anthony Boucher of The New York Times Book Review, who dubbed Target “the most human and disturbing novel of the hard-boiled school in many years.”

All these decades later, The Moving Target still impresses with its vivid prose and carefully rendered characters, plus its plotting mix of greed, broken trust, and festering disillusionments. While it’s tougher and more cinematic than some of Macdonald’s 17 subsequent Archer novels, Target hints at what will become more obvious as the series progresses: the author’s interest in the psychological roots of criminal behavior. The story finds L.A. private investigator Archer, a 35-year-old ex-cop with a sardonic streak (“Most of my work is divorce. I’m a jackal, you see”), being hired by the dysfunctional family of Ralph Sampson, an oil millionaire from “Santa Teresa” (a fictionalized Santa Barbara). It seems the alcoholic Sampson has vanished. His younger, paraplegic second wife figures he’s off on a bender, rather than having been kidnapped. But Albert Graves, a former district attorney and onetime Archer colleague, asks that she hire the P.I. to at least locate the man. It’s a task more easily assigned than accomplished, leading the shamus into a circle of suspects that include Sampson’s beguiling but drifting daughter, Miranda; Alan Taggert, the tycoon’s pretty-boy pilot and the elder Graves’ rival for Miranda’s affections; a sun-worshipping holy man, Claude, to whom Sampson gave a mountain retreat; as well as a downwardly mobile actress with an astrology bent, a forgotten piano player, low-IQ bruisers, and even human traffickers.

Many editions of The Moving Target have appeared since its debut. To celebrate the book’s seven decades in print, I offer 25 of the best and worst covers it has worn around the world.

__________________________________

ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITIONS

__________________________________

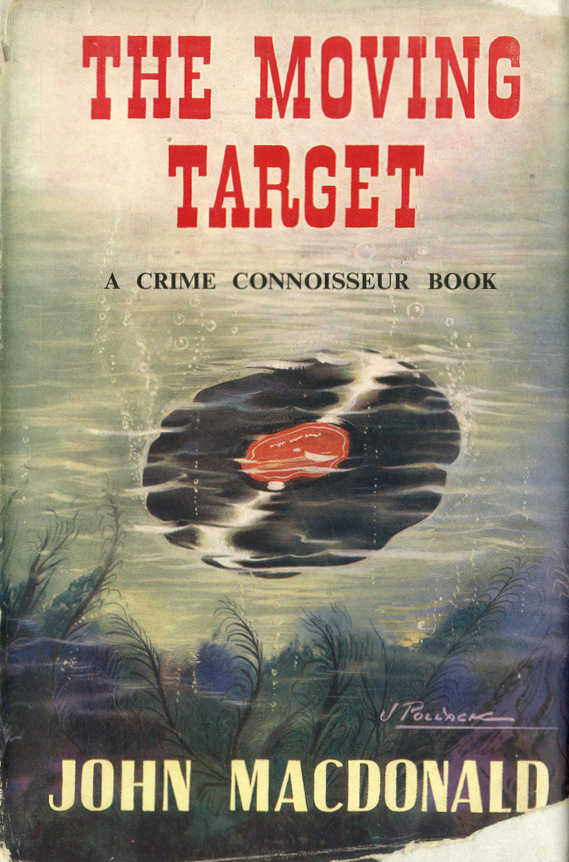

Alfred A. Knopf (U.S.), 1949: Millar spent nearly a year writing and then rewriting his first Lew Archer novel, which he originally titled The Snatch. And though it wasn’t the sort of “literary” work he’d hoped to build his career on, he thought it quite salable. So he was surprised when his New York-based publisher, Knopf, initially rejected the yarn, complaining that it was “fair to middling run-of-the-mill stuff” with a “perfectly impossible” title. (Another 22 years would pass before Bill Pronzini revived The Snatch as the name of his own debut private-eye novel.) Knopf insisted that Millar make multiple revisions and agree to a reduced purchase fee before it would accept his book as The Moving Target, released—on April 11, 1949—under the pseudonym “John Macdonald,” which were the first two names of the author’s father. (Millar chose a pen name in order to avoid confusion with his wife, Margaret Millar, who was already a respected mystery writer.) Artist Bill English’s bullseye motif for that premiere edition’s dust jacket inspired several subsequent Moving Target covers.

Pocket (U.S.), 1950: Illustrator Harvey Kidder based this paperback front on a scene located deep into the novel, which finds a bruised and battered Archer being held involuntarily on one of L.A.’s Pacific Ocean piers. The detective’s only hope of escape is to wield a “rusty file” (not a knife as the cover lines contend) against his thuggish captor, and then try to survive as they tumble together into the chilly waters below.

Cassell & Company (UK), 1951: When The Moving Target finally reached hardback publication in Great Britain, the name of Millar’s protagonist was “inexplicably changed to Lew Arless,” recalls editor Kevin Avery in his gorgeous 2016 book, It’s All One Case: The Illustrated Ross Macdonald Archives. More familiar was the dust jacket imagery, by English paperback painter John Pollack, who focused on a jazz record cast into the ocean off Santa Teresa, one of many such vinyl recordings disposed of hastily by a key player in the story, hoping to throw Archer—er, Arless—off his scent.

Pan (UK), 1954: That peculiar “Lew Arless” handle followed the fictional sleuth into his maiden British paperback appearance. However, his creator’s byline changed. As Tom Nolan explains in Ross Macdonald: A Biography (1999), after The Moving Target’s American release, New York writer John D. MacDonald—whose short stories had found homes in “slick magazines and detective pulps,” but whose debut novel, The Brass Cupcake, wouldn’t see print until 1950—contacted Ken Millar to complain about readers confusing them with one another. Millar agreed to add a middle initial, “R.,” which later became “Ross,” and his sophomore Archer novel, The Drowning Pool, was credited in the States to John Ross Macdonald (as were three subsequent entries in the series). That same nom de plume graced Pan’s 1954 softback version, the cover illustration for which is credited to frequent Pan contributor R. Sax.

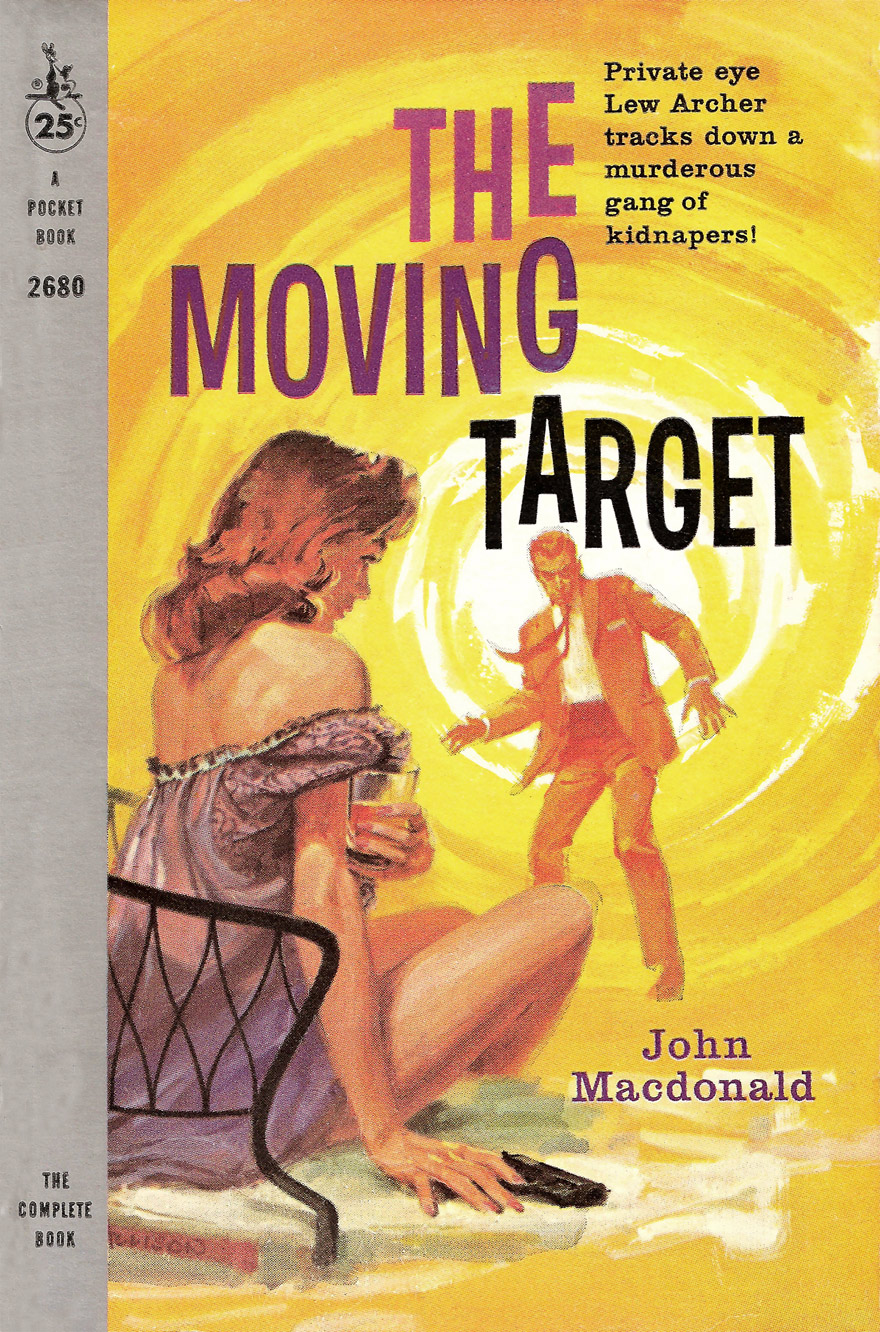

Pocket (U.S.), 1959: Again, we’re given the target device, only this time it’s stylized to also suggest Southern California’s oft-searing sunshine. Jerry Allison’s artwork depicts Archer seemingly startled by an underclad but well-armed Miranda Sampson, whose description on the “Cast of Characters” page in this particular edition reads: “The millionaire’s redheaded, green-eyed daughter was just becoming conscious of the full ripening of her powers, and she wasn’t quite sure what to do about it.” Can Macdonald’s P.I. withstand her abundant charms with any greater equanimity than the other males in this tale?

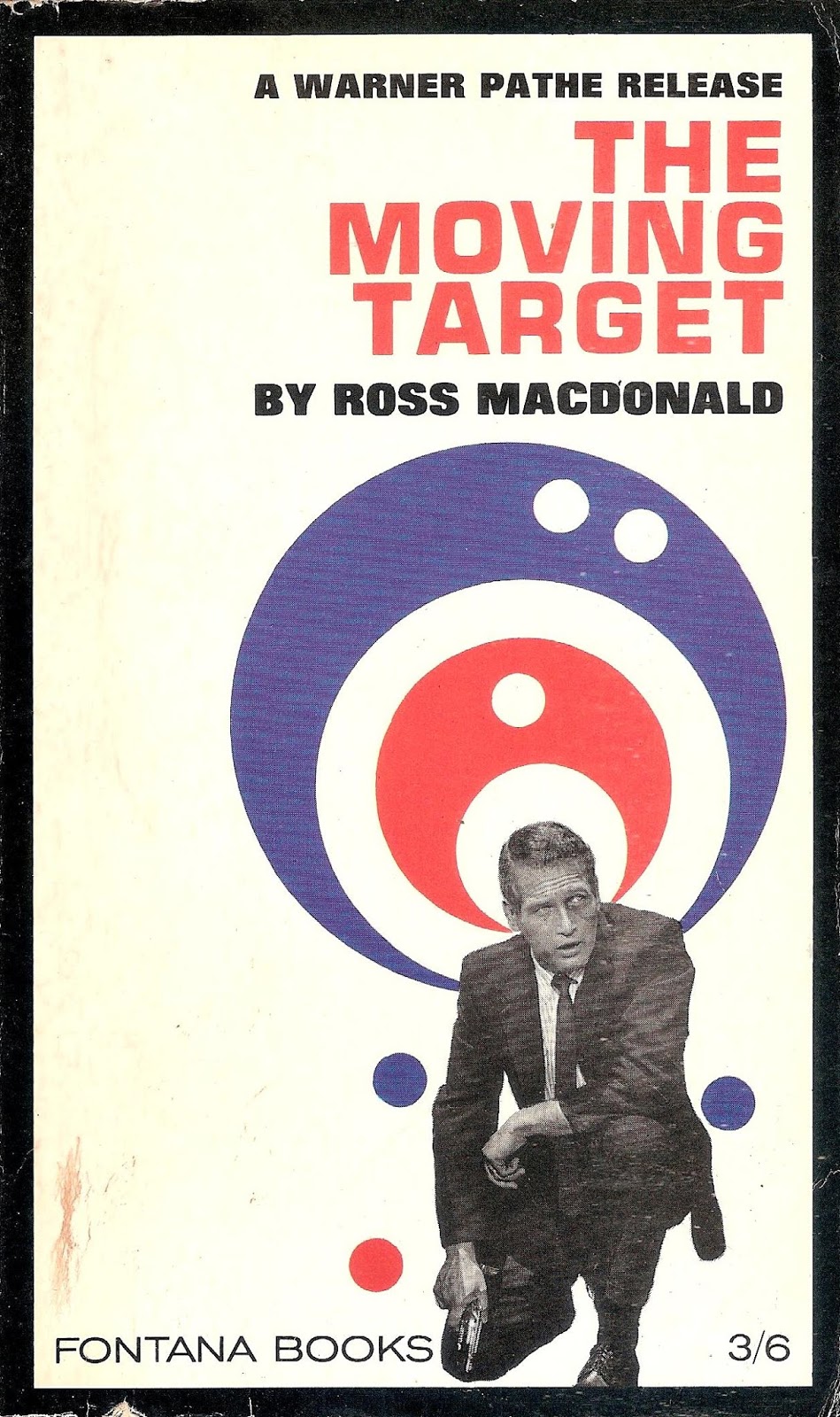

Pocket (U.S.), 1966: In 1964, novelist/screenwriter William Goldman persuaded producer Elliott Kastner to option The Moving Target for big-screen adaptation. Warner Bros. Studios was interested, too; however, it wanted exclusive rights to Lew Archer for a future movie series. When Millar balked, declaring he wouldn’t sell those rights for less than $50,000, Warners decided to use the story Kastner owned, but change both its title and the detective’s surname. Goldman, who penned the script, chose Harper in both cases, because it sounded so much like Archer. Kastner had imagined Frank Sinatra in the starring role, but after that crooner/actor declined, he turned to the younger Paul Newman, who soon appeared on Pocket’s movie tie-in version of the novel.

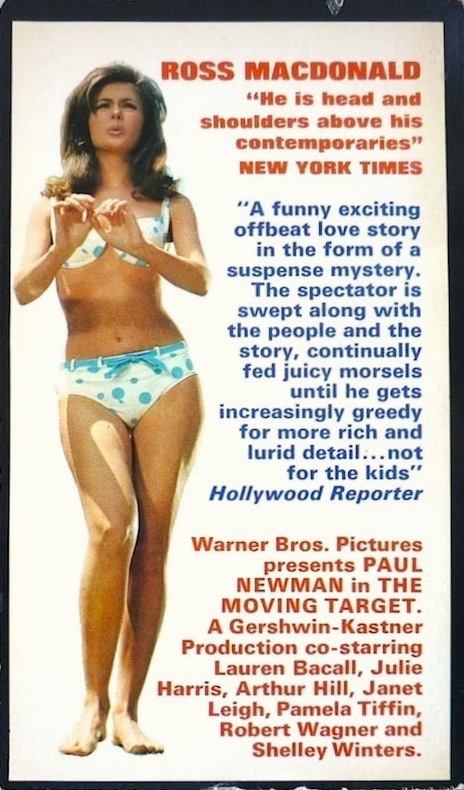

Fontana (UK), 1966: Harper debuted in Los Angeles in February 1966, but the picture reached British theaters months later as The Moving Target. Like its American counterpart, the UK paperback tie-in edition was generally dull-looking. Yet it employed a modified bullseye on its front, and on the backside, it went full cheesecake, offering a color shot of mid-20s actress Pamela Tiffin, as she appeared playing Miranda Sampson in a poolside dancing scene early in the movie.

Fontana (UK), 1971: In the early ’70s, the British paperback imprint Fontana issued a line of Lew Archer novels that promoted Macdonald’s name in a larger font than his titles, reflecting the author’s post-Harper prominence. Clearly directed at male consumers, these books boasted photos of women’s body parts together with carefully arranged props—guns, badges, knives, and axes. While the weapons were easily identified, the anatomical backdrops were occasionally less so. On The Moving Target, for instance, is that paper shooting target tucked beneath a woman’s pendulous breast…or trapped in a butt crack?

Bantam (U.S.), 1974: This is the softcover edition I first enjoyed, part of a uniformly designed set that many readers still consider the height of Archer series branding. Each book front comprised an arresting rectangular photograph (commonly of a woman) beneath the title and author’s name (both of which appeared in bold, shadowed type); in addition there was mention of Macdonald having been installed in the Mystery Writers of America’s pantheon of Grand Masters (after failing three times to win one of the MWA’s coveted Edgar Awards) and a quote from William Goldman’s rapturous review of Macdonald’s 1969 Archer yarn, The Goodbye Look (“the finest series of detective novels ever written by an American”). The same general format was picked up in the opening title sequences for two TV projects based on Macdonald’s work: a 1974 series pilot, The Underground Man, starring Peter Graves and based on the novel of that same name; and Archer, a short-lived 1975 drama that cast Brian Keith as Macdonald’s P.I.

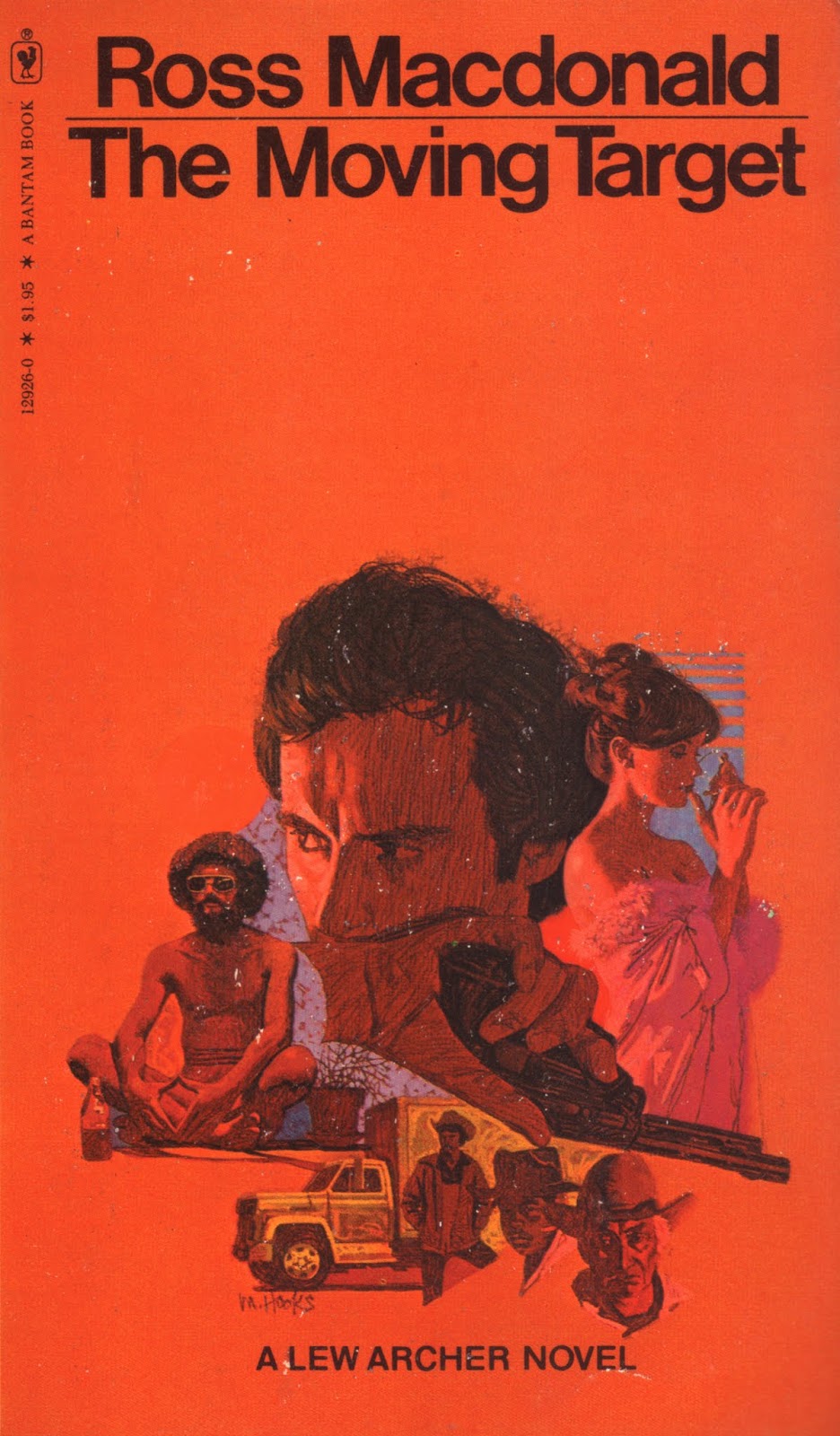

Bantam (U.S.), 1979: Mitchell Hooks’ cover painting for The Moving Target managed to encompass a little bit of everything: his central portrait of a youngish, pistol-toting Archer; cult leader Claude, who’s in the story is called “a dirty old goat with a foghorn voice and the nastiest eyes I ever looked into”; 20-year-old Miranda, once again challenged in the way of keeping clothes on her back; and a truck around which men loiter, presumably illegal migrants. Replacing Bantam’s beloved photo editions, Hooks’ more than a dozen Lew Archer book fronts initially drew skepticism, but have since gathered innumerable fans.

Gregg Press (U.S.), 1979: This antiquarian edition’s dust jacket, with its simple serifed type and drawing of a human eye—suggesting the old Pinkerton National Detective Agency logo, only with a target for a pupil—isn’t the most imaginatively designed of this bunch. Yet it was evidently part of a limited reprint series curated by Manhattan bookseller/editor Otto Penzler, and contained an introduction by crime novelist Thomas Chastain.

Bantam (U.S.), 1984: Released a year after Macdonald’s death, at age 67, this cover showcases English artist James Marsh’s nightmare version of that old hand gesture suggesting a pistol cocked and ready to fire. Should we call this a smoking hand-gun?

Warner (U.S.), 1990: There are enough scenes in The Moving Target of Archer wheeling his car through the coastal mountains and canyons around the City of Angels, that it’s impossible to determine which one inspired this dramatic paperback image by Gary Kelley. Then again, maybe none of them did, as Archer drives a blue convertible in the story, and the vehicle shown here is clearly no slick ragtop ride.

Vintage Crime/Black Lizard (U.S.), 1998: Cover designer Ingsu Liu was probably going for moody with this front, but she wound up with murky, instead. Between the low lighting and blurry focus, it takes a while to identify the photo’s subject; and then we are left wondering what level of threat the man—Archer?—actually faces. Is that some variety of weapon at the lower right, or just part of a colorful jukebox?

__________________________________

FOREIGN-LANGUAGE EDITIONS

__________________________________

Mondadori (Italy), 1953 and 1975: “I like a little danger,” Archer tells Miranda at one point. “Tame danger, controlled by me. It gives me a sense of power, I guess, to take my life in my hands and know damn well I’m not going to lose it.” Not that he can be entirely confident of his longevity. In fact, the risks the P.I. takes here—from trespassing to speeding along treacherous roads to mouthing off at cops and confronting kidnappers—help make Target one of the most dramatic Archer outings. The two editions above, from Mondadori’s giallo (“yellow”) line, capture the imminent jeopardy awaiting Macdonald’s man. The cover on the top was done by Milan illustrator Carlo Jacono, while the other is credited to Oliviero Berni.

Skarabee B.V. (Dutch), early 1970s. Artist Robert McGinnis has painted only one cover for a Ross Macdonald paperback during his long career—and this isn’t it. The art featured here (with a male lead looking uncannily like actor James Coburn) was instead borrowed from M.E. Chaber’s The Bonded Dead, a Milo March tale released by America’s Paperback Library in 1971. McGinnis authority Art Scott estimates that this Dutch translation of Target probably hit bookstores “within a year or two [after that], but maybe not.”

Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verl (Germany), 1986: Between this edition’s brutal photo and its alternative, hard-bitten title (Reiche sterben auch nicht anders translates as “Rich people do not die any differently”), one can hardly mistake it for a cozy whodunit.

Editorial Laia/Alfa (Spain), 1987: There’s something banally literal about this illustration, like a college design project developed from a list of essential components. A running man? Check. A gunsight’s crosshairs trained on that individual? Check. Bullet holes? Check. OK, on to the next assignment.

BB Art (Czech Republic), 1995: Methinks the artist here might have been confused. The Moving Target (or “Moveable Target,” as I’m told is the direct English translation of Pohyblivý Terč) isn’t a TV tie-in adaptation of a vintage crossover episode mixing Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer with WKRP in Cincinnati. Yet doesn’t that pair on its face look an awful lot like actors Stacy Keach and Loni Anderson?

Editions 10/18 (France), 2003: What titillates European males evidently differs from one nation to the next. While Fontana gave Brits naked body bits, this French publisher presented Macdonald enthusiasts with…car porn. Its paperback series delivered intimate shots of mid-20th-century automobiles—the side panels of classic “woodies,” the sweeping engine hoods of convertibles, old-fashioned running boards, sparkling grillwork (as on Cible mouvante), and even, for The Far Side of the Dollar, a simple door handle. Are you now craving a cigarette as much as I am?

Yuanliu (China), 1999: No, no, no, a thousand times no! A skeleton caught in a crazy light show—is this a classic detective novel or a YA disco horror yarn?

Metaixmio (Greece), 2013: Despite its use of elements that are now clichés on Macdonald’s book—guns and a bullseye pattern—this cover’s bold, clean presentation is actually quite eye-catching. Only one minor problem: the Greek title doesn’t exactly match the art. Google says it means “Moving Goal,” not Moving Target.

Gallmeister (France), 2012 and 2018: Finally, a couple more striking French fronts. On top, the illustrator’s presentation of a paper marionette capitalizes nicely on the author’s suggestion in this novel that everyone—Archer not excepted—is susceptible to manipulation. Below that, we have one final spin on bullseye imagery, this time blended with a succession of silhouettes showing an armed man in either flight or pursuit. My issue with this second cover’s art is that, while it again hits the right messaging marks, it might fit just as easily on dozens of other modern P.I. novels. There’s no sense of this book being anything special—and it is. While firmly grounded in detective pulp traditions, The Moving Target made clear in 1949 that a “new-type detective” (as Archer calls himself) was needed in the unraveling society of post-World War II America, someone who could be both sleuth and psychologist.