Nobody wrote scoundrels the way Ross Thomas could. His heroes all had checkered pasts, though often with a Bogartian streak that led them to do the right thing against their own self-interest. His villains were a spectacular assortment of con men, spies, shady politicians, corrupt cops, wheelers, dealers, fixers, and schemers. His complex plots often revolved around political intrigue and backroom chicanery leading to sudden violence, and featured double-, triple-, or quadruple-crosses, so much so that it might not be until the very end that you knew exactly who had done what to whom.

All of this, in a too-brief span from 1966 to 1994, was written with keen intelligence, sharp humor, and a brilliant gift for character, description, dialogue, and intimate observation. So good was he at all of the latter that Stephen King called him “the Jane Austen of political espionage.” His worldview was jaded, but to charges that he was overly cynical, Thomas only responded, “If there is a trace of cynicism in my books, it’s only based on reality. People are always saying, ‘Things can’t be as bad as you make them,’ and I say, ‘No, they’re worse.’”

Does any of this sound familiar to you?

Besides, he knew what he was talking about. Born in Oklahoma in 1926, Thomas saw action in the Philippines during World War II, then became a reporter in Louisiana. (“Finishing school,” he remembered fondly. “Louisiana used to have the best, hardest, most vicious state politics around. If you were interested in politics, it was the place to be.”) Then, in dizzying succession, he returned to Oklahoma to become the public relations director for the Oklahoma Farmers Union; moved to Denver to do the same for the National Farmers Union; set up a PR firm that handled campaigns for both Governor and Senator in Colorado (the gubernatorial candidate was a Democrat, the senatorial a Republican; Thomas won the first, lost the second); chucked it all to go to Bonn, West Germany, as a correspondent for the Armed Forces Network; chucked that to go to Nigeria to manage a prime ministerial campaign for tribal chief Obafemi Awolowo (who lost and got thrown in jail by the victor); then headed back to Washington, where he worked closely with two major unions to get their presidents elected and re-elected, as well as acting as a consultant to “various branches of the American government.”

What does that last one mean? Many people have thought there was a fair amount of spook-related activity sprinkled in amongst all that traveling and managing and consulting. Thomas himself would only admit to being a “former civil servant.” His wife, when asked about it point-blank, simply smiled and said, “Not that he told me.”

So when, at the age of 40, he found himself a bit bored one year—“I always got bored with jobs after two or three years,” Thomas said—and thought he might try his hand at a novel, he knew he had plenty of raw material. As he often told and re-told the story in later years, according to fellow crime writer Lawrence Block, “I set up my typewriter and started hitting the keys, and when I was done—“ in six weeks (!)—“I had a couple hundred double-spaced pages and didn’t know what to do with them, so I called a writer friend of mine in New York and told him what I’d done. ‘Now why would you do something like that?’ he wondered. ‘Well, go out and buy some brown wrapping paper and wrap your manuscript in that. And then address the parcel to this fellow at William Morrow, in New York, and mail it to him. And enclose return postage, so he can send it back to you.”

“People are always saying, ‘Things can’t be as bad as you make them,’ and I say, ‘No, they’re worse.’”Two weeks later, the editor called and bought the book. It was called The Cold War Swap, was set in Bonn, and revolved around a reprehensible little scheme cooked up by an American intelligence agency concerning scientists and the Iron Curtain. Published in 1966, it already had all of Thomas’s trademark elements in place and would go on to win the Edgar for best first novel. It also introduced two Americans, a former Army special ops officer and now saloonkeeper named “Mac” McCorkle and a lethal polyglot spy named Mike Padillo, both of whom relocated to Washington, DC and would reappear as partners in three more books, Cast a Yellow Shadow (1967), The Backup Men (1971), and Twilight at Mac’s Place (1990).

It was rare for Thomas to repeat his protagonists. Of his twenty books as Ross Thomas (he also wrote five others using a penname, about which more later), thirteen of them were stand-alones. The only other exception Thomas made was for the superlative duo of six-foot-two Artie Wu, who as “the illegitimate son of the illegitimate daughter of the last Emperor of China,” was a pretender to the throne, and Wu’s partner since they were boys in an orphanage together, Quincy Durant. Featured in three books—Chinaman’s Chance (1978), Out on the Rim (1987), and Voodoo, Ltd (1992)—you might call them soldiers of fortune, “fortune” in this case meaning both money and adventure, and very large quantities of both, both in the U.S. and abroad. Out on the Rim, for instance, features the two of them, along with three others, helping to execute a scheme to deliver five million dollars to a guerrilla leader in the Philippines. It has not escaped the attention of any of them, however, that five million divides nicely by five—and even more nicely by less than five. And the games begin.

All of these books use elements from Thomas’s own background in one way or another, as do the stand-alones—union politics in The Porkchoppers (1972) and Yellow Dog Contract (1976), the Nigerian election in The Seersucker Whipsaw (1967), Washington D.C. shenanigans in Briarpatch (1984), If You Can’t Be Good (1973), and many others.

The very final book, published shortly before Thomas’s death, bears one of his quintessential titles for one of his quintessential themes, Ah, Treachery! (1994). It features an ex-Army major named Edd “Twodees” Partain as he searches for $1.2 million in stolen illegal political contributions while trying to save his neck from former comrades trying to expunge the record of a covert op in El Salvador. The plot, as with all Thomas books, is intricate and up to date, the characters appropriately shady, and the humor evident throughout (a veterans’ group, for instance, is called Victims of Military Intelligence Treachery—you can figure out the acronym).

“Ah, treachery!” murmurs one character to another. “One of history’s favorite shortcuts.”

Right up there with assassination.”

One can only imagine what Thomas would have made of the state of politics today. He would have been appalled, of course—and no one would have written about it better.

__________________________________

THE ESSENTIAL THOMAS

__________________________________

With any prolific author, readers are likely to have their own particular favorites, which may not be the same as someone else’s. Your list is likely to be just as good as mine—but here are the ones I recommend.

The Fools in Town Are on Our Side (1970)

“Hain’t we got all the fools in town on our side? And ain’t that a big enough majority in any town?”

—Mark Twain, Huckleberry Finn

Article continues after advertisement

Even if it weren’t such a good book, I’d have picked this one anyway because of its title, which has stuck with me for, geez, nearly fifty years now.

It crosscuts seamlessly in time and place among the Deep South of the late 1960s, Hong Kong in the early 1960s, Texas in the early 1950s, and Shanghai in the late 1930s, but its main emphasis is on a fictional Gulf Coast city named Swankerton, which is awash in drugs, gambling, and prostitution. A disgraced former intelligence agent named Lucius Dye is hired to clean it up by an eccentric named Victor Orcutt. Dye is a little taken aback by the man—“He smiled a lot, but it didn’t mean anything, and I had the feeling he would smile just like that if a dog got run over”—and even more by his plan. Orcutt wants Dye to take the depravity further: “To get better, it must get worse. What I want you to do is to corrupt a city. So corrupt that even the pimps will vote for reform.”

Dye teams up with an ex-police chief named Homer Necessary, a man with one brown eye and one blue eye, “neither of them contain[ing] any more warmth than you would find in a slaughterhouse freezer.” Together they dive right in, and everything goes according to plan until it doesn’t, and that’s when things get really interesting. Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Texas? They all play a part, too.

Chinaman’s Chance (1978)

Thomas always claimed that an old editor once took him aside and gave him some advice. “Two things you never want to write about,” he said. “Dwarves and Chinamen. Nobody wants to read about dwarves or Chinamen.” Thomas thanked him and swore he’d remember. His next book was Chinaman’s Chance. The one after that was The Eighth Dwarf. An apocryphal story? Probably, but who cares?

Chinaman’s Chance was the first adventure featuring Artie Wu and Quincy Durant, and the first paragraph is classic.

“The pretender to the Emperor’s Throne was a fat thirty-seven-year-old Chinaman called Artie Wu who always jogged along Malibu Beach right after dawn even in summer, when dawn came round as early as 4:42. It was while jogging along the beach just east of the Paradise Cove pier that he tripped over a dead pelican, fell, and met the man with six greyhounds. It was the sixteenth of June, a Thursday.”

Wu and Durant are looking for a mark to buy a map from them which purports to show where the U.S. embassy buried two million dollars in cash in Saigon right before fleeing the city ahead of the Viet Cong. The man with the greyhounds, in turn, is looking for someone who might help him out with a problem—his wife’s sister has disappeared after a shocking event. She was living with a congressman whose estranged wife shot and killed first him and then herself—a classic murder-suicide—except that he doesn’t think it happened that way, his sister-in-law’s in trouble, and the cops are curiously indifferent about it all. Things are about to get dicey, and he figures he needs someone even dicier to get to the bottom of it. That would be Wu and Durant. Artie’s only question is, “Will it be cash or check?”

It turns out there are a whole lot of other questions he should have asked, too.

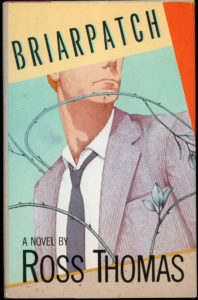

Briarpatch (1984)

This one got Thomas his second Edgar, for the year’s best novel, and deservedly so—it’s one of his very finest.

Benjamin “Pick” Dill is an investigator for a Senate subcommittee who gets the news one day that his sister, a homicide detective back in their hometown, “the capital of a state located far enough south and west to make jailhouse chili a revered cultural treasure” (read: Oklahoma City), has been blown apart by a car bomb. In describing Dill, Thomas shows off his descriptive chops: “The mouth [was] thin, wide, and apparently remorseless, or merry if the joke were good, the company pleasant…The eyes were large and gray and in a certain light looked soft, gentle, and even innocent. Then the light would change, the innocence would vanish, and the eyes looked like year-old ice.”

Dill flies home for the funeral, and finds mounting evidence that his sister may have been dirty—but he doesn’t buy it for a moment. Instead, he uncovers a web of murder and corruption that goes back deep into his own past, his sister’s very complicated history, and the city’s most basic underpinnings. A lot of blood has been spilt, a lot more is still to come.

Briarpatch contains all the plot twists and humor for which Thomas is known, but there’s also a distinctly darker tone. More than anyone else, Dill feels like a stand-in for Thomas himself and his world-view.

“After he hung up, Dill felt as if he had spent the past hour or so wandering through a vast and largely uncharted land with one of those ancient maps that read: Here There Be Monsters. Dill knew the map was right. He had come this way before. Yet, you still don’t believe they really exist—the monsters. No, that’s wrong. You believe they exist all right, but after fifteen years of watching them, writing about them, and even tracking them down, you still think they’re normal, harmless, and domesticated. Even housebroken.

“But what if they, after all, are the norm and you are the aberration?”

__________________________________

BOOK BONUS

__________________________________

As mentioned above, Thomas also wrote five books under the penname of Oliver Bleeck. They were about a man named Philip St. Ives, a professional “go-between” with a taste for intrigue and fast living who is trusted by the good and the bad alike to recover kidnap victims and stolen property, among them a tenth-century African brass shield, a rare book by Pliny, the notable Sword of St. Louis, and the “fat-headed U.S. Ambassador to Yugoslavia.”

The books are short, fast, entertaining, and sound exactly like Thomas. They’ve definitely lesser works compared to the others, but if you like his voice, there are worse ways to spend an hour or two.

Lawrence Block has a vivid memory concerning one of the books, Protocol for a Kidnapping (1971). He particularly enjoyed two friends of St. Ives who show up during the rescue operation in Yugoslavia and join him not only in the mission, but in some delightful banter: “The readers looks forward to more of it in later books—until after the plot has been successfully resolved, a stray bullet zips in and kills one of the buddies. Why??? ‘I could just picture these clowns joking around in book after book,’ Thomas told him, ‘and I decided the hell with all that, so I nipped it in the bud.’”

__________________________________

MOVIE BONUS

__________________________________

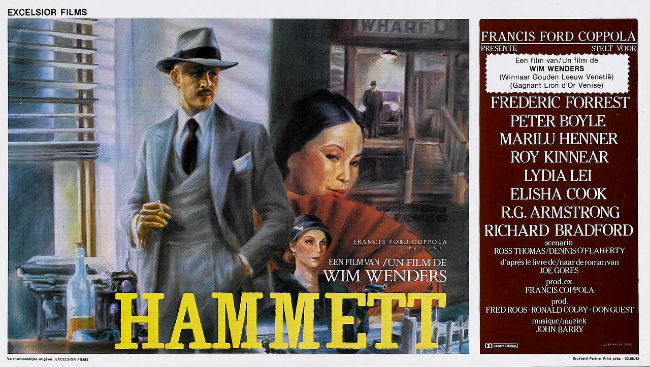

Surprisingly, little of Thomas’s work made it to the big screen. He was a co-writer on Wim Wenders’s 1982 Hammett, featuring Frederic Forrest as the real-life Dashiell Hammett investigating a crime, but it was generally regarded as a “well-intentioned failure.” Thomas also played a small role as, what else, a corrupt local politician. He also wrote the screenplay for a film called Bad Company, starring Ellen Barkin and Laurence Fishburne. Only one of his own books, though, became a movie, one of the Oliver Bleecks, called The Procane Chronicle, which, retitled St. Ives, starred Charles Bronson and Jacqueline Bisset.

In an article about the experience, Thomas wrote, “After five minutes of watching, I realized that nothing of mine was going to be used except the skeleton of the plot. When I had met Charles Bronson on the set, he had told me, ‘I haven’t read your book.’ That’s okay, I said, I didn’t see your last picture.”

Thomas’s wife once said that the subtleties and ambiguities of his books appeared to prevent them from becoming movies: “He didn’t mind. What entertained him and his readers didn’t necessarily translate to the screen very easily.”

Besides the movies, Thomas also did some work for television, with over a dozen episodes of such shows as Simon & Simon, Hardcastle and McCormick, Tales of the Unexpected, and Tales from the Crypt. Of more interest, Briarpatch was greenlit this July for a pilot by USA Network. In a gender switch, Rosario Dawson will play Washington investigator Allegra “Pick” Dill on the trail, as per the book, of the murderer of her homicide detective sister. No air date is set, there might never be an air date…but I’d watch that.

__________________________________

HOMMAGE BONUS

__________________________________

“The redheaded detective stepped through the door at 7:30 A.M. and out into the August heat that already had reached 88 degrees. By noon the temperature would hit 100, and by two or three o’clock it would be hovering around 105. Frayed nerves would then start to snap and produce a marked increase in the detective’s business. Breadknife weather, the detective thought. Breadknives in the afternoon.”

That’s the opening paragraph of Briarpatch, and a justifiably famous one. If anything about it, however, seems to ring some sort of bell in the back of your brain, that’s because you’re thinking of this, the first paragraph of Raymond Chandler’s short story, “Red Wind,” and one of his famous openings:

“There was a desert storm blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Ana’s that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that, every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ throats.”

This is no accident. Thomas was a great fan of Chandler’s, and had a personal connection besides, as he wrote in the Washington Post once:

“One hour and thirty-five minutes before we were to land on the beach of an island in the Philippines called Cebu, the first scout handed me something called Farewell My Lovely, by someone called Raymond Chandler. It was January of 1945, and I was eighteen.

“The title sounded as if it could have been thought up by the American equivalent of Agatha Christie….Imagine my surprise, as Dame Agatha, might say, when I opened it to discover Philip Marlowe over on that mixed Central Avenue block in east Los Angeles.”

The scout was soon dead, and Thomas lost the book on the beach. Taking over his job, Thomas spent the next 100 days or so wondering who Velma was. “I decided,” he said, “I needed to be Philip Marlowe safely back in Los Angeles in that palmy year of 1940—in a time that would never change. It was a harmless enough notion that probably kept me sane.”