Last week, Sara Gran and I had an hour-long conversation on Zoom. We were supposed to be talking about her new publishing company, Dreamland Books, and its first release, Gran’s novel The Book of the Most Precious Substance. Instead, our conversation ended up touching on almost every hot button topic in the genre, from gender politics to publishing issues. Our conversation was also very 2020/1: both of us bragged about washing our hair before the interview (it was, indeed, the first time someone had seen me in days). Sara Gran had recently gotten a real haircut, but assured me that she’d spent much of the pandemic cutting her own hair while smoking weed. (The drawback to this approach is that it apparently takes hours). I told her that while I thought I could do almost anything while stoned, I drew the line at haircuts. After that truly amazing icebreaker, we sat back and started talking crime fiction.

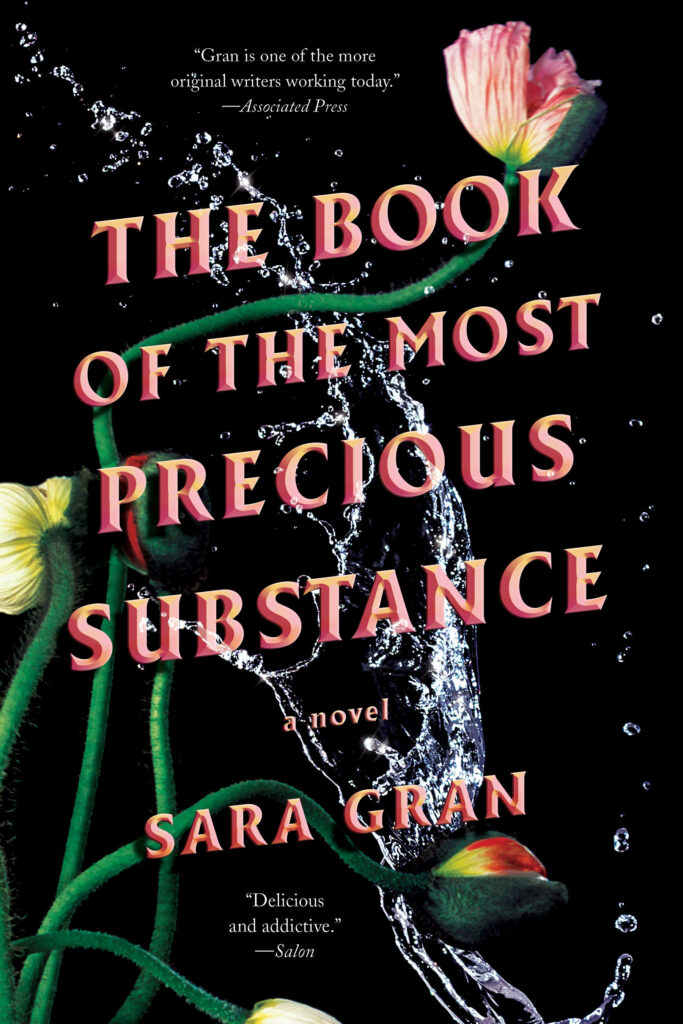

Here is a condensed transcription of our interview, edited for flow and clarity. Scroll down for the official cover reveal for The Book of the Most Precious Substance.

MO: Let’s talk about your new book, the first release from your new publishing company. I love combinations of rare books and superstition!

SG: I wanted it to be fun! In the 90s, there were a bunch of thrillers (like In the Cut by Susanna Moore, Damage by Josephine Hart) that were about middle-aged women. These were sexy, fun books, but they were well-written and good reads, not like what’s passed off as popular fiction today. They were absorbing, and fun, and really not heavy. So you write what you want to read and what you miss.

MO: I hope some of these 90s classics reenter the cultural consciousness (now that people are remembering that middle-aged women exist).

SG: That’s one reason that I’m doing this—publishing will discover that a large group of people, like human females past 40, or Black people, these huge categories of humans, they will discover they exist for a while, and market books toward them, and then let it go again and forget. When one book doesn’t sell as expected, the assumption is that “those people just aren’t buying books anymore.” They’re applying a totally different standard.

MO: This reminds me of the fact that Black college-educated women buy the most books of any reader group.

SG: That’s a really good point. It’s a weird thing because women write more than men, and sell more than men, and women buy more books than men, and people think of publishing as this female-dominated industry, but if you look at or above the editor-in-chief level, there’s very few women.

MO: And now you’re stepping into your publisher shoes.

SG: I realized this morning before we talked that tomorrow is the 20th anniversary of publishing my first book. So it’s a fun time to start my own publishing company because I’ve been wanting to do this since my first book (which was a great experience, I feel very lucky to have gotten published with no agent). But I remember thinking, “Should I just start my own publishing company? Eh, no, no one does that, maybe there’s a reason no one does that.” And now, 20 years later, I’m finally doing it, so it’s a nice moment for me.

MO: How does starting your own publishing company compare to working with a traditional publisher? Do you think it’s a better experience for writers?

SG: Well, I might go crawling back, that’s always a possibility…But so far it’s been really fun, and much more fun than working with a big publisher.

MO: I should probably have started by asking you to tell us a bit about the new publishing company.

SG: I’m starting with my book that you read, the Book of the Precious Substance, so I can work out any kinks. There’s lots I’m sure I’m doing wrong! Distribution is the biggest hurdle, I’m in the middle of trying to work that out. And then I want to publish other people as well! I want to keep it really small, so it’s just myself and maybe an assistant, and do 2-5 books a year tops, and really throw a lot of attention at each book.

MO: How does your writer hat compare to your publisher hat?

SG: Well, I have another hat, which is a producer hat, because I’ve been working in TV for 10 years. It’s funny, because the expectations for a writer of a book versus a TV writer are completely opposed to each other. In publishing, you’re always infantilized a little bit as the writer, you don’t get to participate in the grown-up conversations, and I have always found that frustrating, especially after 10 years in Hollywood where as a writer you’re also expected to be a producer, contributing to huge decisions like casting and multi-million dollar budgets, and where to film, and now during Covid, how to keep your crew safe. I’ve been a showrunner, I’ve produced development projects, so the expectation in publishing that I wouldn’t contribute to any major decisions or that my opinion was not as valuable, where I’m working this other job where I’m making all the decisions—it was difficult to reconcile. And I’m bossy just to begin with! I’m bossy and independent and like doing things myself.

A lot of the decisions are also creative ones, and I wanted to make a package that really fit the book and make sure the design elements help tell the story. I worked with a great designer, Zoe Norvell, and we worked really closely together to come up with this package that I think helps tell the story and enhance the experience.

MO: Let’s talk about the book. So, the sex magic—I loved it! What was the inspiration?

SG: I’ve always been interested in the weird shit that people do, and the weird shit that people believe—I think all these things have some truth in them, and none of them are entirely true or the whole story. The world exists in gray areas, in areas between real and not real. I have never written explicit sex stuff before, it was always a bit of a fear for me, but its good to lean into your fears as a writer, to make yourself uncomfortable, especially 20 years after publishing your first book.

MO: So much of sex is so unintentional—it seems like a lot of the magic in our actions is robbed by our inability to be intentional with those actions. If sex is casual, how can it be magical? You have to be intentional to find the magic in your actions.

SG: That’s a really good point, and that’s what frees my character to get back into sex after not being interested in so long, that it has this intentionality to it. There’s a frame of, “I’m not really making myself vulnerable” that she can hang these acts on.

MO: In that sense it reminded me of a kink, and these ways of being incredibly intentional to get you outside of thinking of your partner based solely on hotness.

SG: If sex magic does work, which I don’t know, the degree to which it would work would be based on producing an altered state, that you are freed from your everyday constraints. According to a podcast I was listening to, good sex should lower your IQ by about 50 points, and put you in a state of stupefaction.

MO: Probably most things that are relaxing are better when you lower your IQ…

SG: We have this guard up all the time, and when you drop that guard, if you do in a ritualized setting, you’re not exposing your vulnerability by dropping that guard.

MO: You have this really interesting reputation for writing books that are smart, entertaining, and cool. There really aren’t that many women crime writers that I can think of that are automatically billed as “cool.” I wonder what that’s about—why aren’t more women considered cool?

SG: Once you’re a middle-aged woman, you have to kind of go to extremes before people think you’re cool, because the default is that you’re a suburban soccer mom (god bless suburban soccer moms). Anything you do to deviate from that assumption will bring you a reputation (hopefully a good one). A lot of female writers feel like they’re being encouraged to be the good girl, the nice girl who just happens to publish a book about bad stuff—that’s the public image you see for a lot of female crime writers. ‘I’m so nice, but I go home and write this dark stuff.’

MO: One of my pet peeves on the internet is all the articles questioning why women love true crime. Women have always been fans of true crime and dark things. It’s such a lazy description: “she looks so nice, but inside she’s so twisted.”

SG: Yeah, I think we’re all a lot more twisted on the outside.

MO: It’s nice that we’re in an era with lots of women with tattoos. That helps.

We talk about tattoos for a bit, and Sara admires mine of a snail. We briefly geek out over medieval marginalia.

MO: Do you have a large rare book collection?

SG: No, I’m not a book collector at all! I collect books that I want to read, and I sometimes collect books and editions that I like, but I do not collect first editions or super-rare books. I can’t afford them (nor would I want them sitting around the house). There’s a theory of collecting best editions, rather than first editions. There’s nothing particularly valuable about a first edition, other than that people have decided its valuable. I’ve never understand the rational of collecting them, although I’ve been happy to sell them many times over the years. I have an enormous collection of weird shit that I want to read. My rule for collecting a book is, am I likely to come by it again. Now I have thousands of books and I need to divest a little bit.

MO: I don’t take care of my books well enough to collect them, alas… I’m going to veer super-left for this next question. Sometimes I think of one of the purposes of CrimeReads as helping depressed people who are surrounded by the happiness industry. As someone who’s written very clear-sighted novels for readers with dark visions of the world, what do you think of the power of literature in helping us feel normal about the thoughts we’re already having?

SG: I think that’s the primary purpose of literature. I hate to say that, because I hate to say any sweeping judgements, so scratch that. I think that’s one of the things that literature can do. I can take a piece of my soul and I can put it into a book form, where your soul can meet it. Or your subconscious, if you don’t believe in a soul, but not your conscious brain and not our political thoughts and opinions. I’m reading so I can take a me and you can find it later and feel less alone. That is the primary purpose.

MO: *heart* I look for fiction that channels my emotions without necessarily representing my experience; and that goes along well with the subconscious/consciousness divide.

SG: It’s dream logic. A director once told me that the reason why the film editing works so well and you don’t really notice if you’re jumping from this view to that view is because that’s how dreams work. And that’s how books work—they have the space to explore dream logic, the logic of the soul, or whatever is under conscious thought. It’s a metaphorical and symbolic language, but not metaphorical or symbolic of anything in particular, just a set of signifiers for things that cannot be put into words any other way. If you could put your subconscious into words any other way, than why the fuck would you write a novel?

We take a break to admire my cat.

MO: How has fan response changed to your Claire DeWitt novels since you started writing them?

SG: Fan response has been one of the most amazing things I’ve ever experienced, I have to say. It’s really changed my conception of what I was doing with my life and what I was writing. My books have not been bestsellers—sales have been good, but not, like, million copies good—but the letters I get tell me that these books really changed something for them, that they are doing things differently than they ever did before. These books have had a huge influence on the people who love them. I feel a bit like I don’t even need to do anything else, I just need to finish this series. And I don’t know if I’ll ever finish the series but I did finish the cycle of the series. The response has been life-altering.

MO: For me, they were a black swan moment—I didn’t think a character like that could exist before I met Claire DeWitt.

SG: It’s only Hollywood and publishing that are still using these outdated gender norms. When I go out in what I call normal America, or anywhere else in Los Angeles, no matter people’s walks of life, no one has these antiquated visions of what women can and cannot do. Hollywood and publishing are in many ways living 30 years in the past in terms of race and gender issues, which is shocking to me because these are supposedly liberal industries, but in reality (and obviously much more in Hollywood than in publishing) there’s still so much catching up to do.

MO: Coming from a bookstore environment, when I moved up to NYC and started learning about publishing I was surprised at how gendered it was in comparison.

SG: It is weirdly gendered. I understand that they want demographic targets for their books, but women are not a demographic. Women are half the population. When it comes to male demographics, there’s more of a breakdown.

MO: As someone raised by a single dad, I’m always surprised by the genres that are coded as male. Women love stories about hot, vulnerable, wounded men, so why are war movies for guys?

SG: When you get into the actual numbers, it gets interesting. Women are the biggest consumers of horror, for example.

MO: Perhaps that’s because female experience often is a horror novel. But with the new abortion laws, women’s lives are more like thrillers, with a countdown.

SG: That’s a horrific but apt comparison. But there are deeper nodes too, in this maternal, human, race to the clock before you die. There’s a deep universality to these sort of traditional genre thoughts. That’s why they keep coming back again and again.

MO: I also love to watch authors be creative within structured bounds.

SG: Raymond Chandler said he didn’t give a fuck about mysteries at all—he said that what he wanted was a frame on which to hang the things that interest him. For me, as a writer, it’s a really positive challenge to take these genres and say why are they so compelling, how do you respect what people love about this genre while also taking this to a more literary place or more innovative place. Those structures give you a lot of freedom because you’re not just out in the ocean floating.

MO: Exactly. You can use the structure, but you don’t need to know who killed the chauffeur. Back to gender – so yes, women are definitely not a demographic, but when I think about times when psychological thrillers have peaked, it’s at peak times of uncertainty in women’s changing roles, back to the 1870s, when the sphere of domesticity is being established during the industrial era. Willkie Collins is a bit earlier, but he’s writing in an era where women increasingly feared being locked up by their husbands in asylums.

SG: Art gives us this outlet for what we can’t say out loud, accessing our deeper core and our deeper fears.

MO: I should take this moment to reassure anyone listening to this interview that your new book is straight-up entertaining.

SG: I hope so! I needed to be entertained, and they say write what you want to read, and I couldn’t find anything quite like what I wrote in this book.

MO: It’s the adventure aspect that really made the book fun for me. It wasn’t just a novel about searching for something, it’s a quest novel.

SG: This is part of why YA is so popular, I think readers have really been missing adventure novels, by which I mean novels with some propulsiveness to them. You don’t have to have lose anything in your story in order to bring these elements in. Just like with literary fiction–you don’t have to lose any of the beautiful language when you also focus on the plot.

MO: That’s probably why I think of you as a writer’s writer—your commitment to combining literary and genre elements.

SG: That’s the ultimate compliment, thank you. That kind of response, to the Claire DeWitt novels—I can die happy now.

This is why Sara Gran is starting her own publishing company—she knows that in a publishing industry full of mergers and motivated by sales, it’s harder and harder to find a place for weird, literary fiction like her own. It’s up to smaller publishers, old and new, to take up the slack. She’s sure they will. Small production companies and new record labels preserved the diversity of film and music after those industries enter a new era of conglomerates.

SG: When people don’t go to the movie theaters, the studios can only make money with the 50 million dollar movie‑there is no place for the 10 million dollar movie. So all these small production companies with real money behind them came up to fill the void. And that’s what’s going to happen in publishing too.

Writers seem less likely than musicians and filmmakers to take some initiative and to start a business and to say I’m taking on that role.

MO: I’m thinking of those horrible royalty deals in the 90s that made musicians all very cautious, when musicians would make no money from a massive hit.

SG: Or they’d be forced to pay for studio sessions…Some of that does happen in publishing, but things have to get bad to a certain degree before people are going to go to an alternative. And hopefully they won’t! But I do wonder if they’ll be more small publishers cropping up. Although often, small publishers offer the exact same contract terms as big publishers. The royalty rates are pretty much the same everywhere all across the board. If you publish with a big publisher, they will ask for more in terms of rights, and now NDAs and morality clauses.

Sara Gran worries that morality clauses and mergers might end up leading to writers being dropped for poor sales, or radical creativity, or being “difficult”. There could be lots of writers soon looking for a new home.

MO: What do you want to see more of in the book world?

SG: I want to see more of people starting their own publishing companies, I want to see more opportunities, and I want to see more works being published by people of color. People talk a lot in Hollywood and publishing about the diversity of people who face the front, the actors, the writers, the “above-the-line people” as we say in Hollywood, but there’s not enough talk about diversity in ownership. It’s ironic working in these fields and hearing people say all the right things and do all the right things, but no change is happening at the top. I would love to see more diversity in the ownership ranks.

MO: You’re really only going to see superficial change, until people think about economics.

SG: And having some of those changes is better than none. Since I’ve been in Hollywood I’ve seen a drastic shift in how women are treated, how people of color are treated, how people of all genders are treated, and it’s definitely for the good, and I don’t mean to minimize those accomplishments, but the real change is going to come to from ownership.

MO: Is it too early to ask you what kinds of books you’re looking to publish?

SG: The answer is, things that I think are great. Books that I think are wonderful and won’t have a home at a traditional publisher. I’m so lucky to know a lot of incredible writers, and a lot of really great writers have an unpublished manuscript sitting around. And that was again another reason why I wanted to do this, because I had unpublished manuscripts sitting around. One I rewrote so much of in the effort to make it saleable that I thought I’d ruined it, and to me that’s heartbreaking. This is what I do with my life. This is what I’ve done for 15 years now. And there was this one book in particular that always ate away at me. I’ve had other books where people told me “you’ll never get this published” and I did, to some degree or to a lesser degree through my own efforts.

But no submissions yet! I have a firm no submissions rule until I know what I’m doing better. I want to publish books that I am proud of. There’s no genre, no type. And I want to give authors more ownership. The number one thing I want to do is to not have a life-of-the-copyright print clause. That’s been another heartbreak for me, is seeing my books go out of print.

We shop talk about how busy editors are these days, how distribution is the biggest challenge for independent publishers, and how much booksellers and readers love swag. As a former bookseller, I lament the fact that there aren’t more bookish posters available for sale. As a former bookseller, Sara Gran agrees, and promises to explore posters as a potential marketing strategy.

And now, the cover of The Book of the Most Precious Substance (which would look very, very good on a poster) is at last revealed: