I am not the only writer I know who watched a lot of television during the pandemic. Too much television. My husband and I parked ourselves on the couch and watched Tiger King (oh come on, you know you did too!), every episode of New Girl (still funny, even the second time), and countless British mystery shows, all of which began to blend together into a seamless, cozy, pacifying blur.

I didn’t mind this. I was so lucky: no one in my family was ill, no one died. We live on a boarding school campus in Massachusetts, so even though the school sent everyone home and moved its academics online for March, April, and May of 2020, we were quite happily stuck in our campus bubble. We spent lots of time hosting “driveway parties” and playing an invented, socially distant lawn game called Bean Bolf. I bought giant bags of flour and my college roommate sent me a sourdough starter in the mail. I sewed masks, which were apparently completely useless, and my kids built bike jumps in the woods. It felt a little like my childhood in the 80s, with some Zoom sprinkled in. Our sufferings were small—infinitesimal—compared to the greater world.

And yet, I missed them. Yes, the teenagers. My writing desk looks out on a large quad, surrounded by four dormitories. On normal days, the quad is filled with kids doing what kids do: laughing, racing each other on scooters, flirting, chasing each other around, tripping because they are trying to walk and watch a show on their phones at the same time. During Covid, though, the quad was mostly empty, except for an occasional faculty child on a solo bike ride, our silly Bean Bolf games, and, once, a bear, who lumbered slowly through the empty quad, amazed at his good luck.

I didn’t realize how much I relied on the small daily dramas of the students for inspiration until they were gone. A few months of watching the same stale television night after night—and writing very little, despite the massive windows of time I had to do so—made me notice that something was changing about the way I was consuming the stories I was watching. I didn’t really care whether the priest in the tiny, weirdly crime-prone English village would find the killer; I didn’t even try to figure it out myself. Because my daily life was lacking in intrigue, no fictional intrigue appealed. The stakes in the real world were much too high; the stakes in the fictional world were way, way too low.

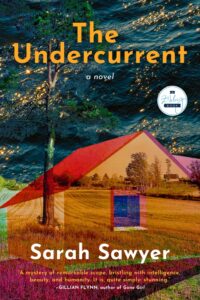

You would think that I would just turn off the television and feed my creative soul with something new and perhaps more stimulating, but it was Covid, so we just plugged along, the same thing every night. In the fall of 2020, my school was lucky enough to be able to open in-person for our students, which was a logistical nightmare but an emotional boon for the young people in our care. Slowly, they returned to campus, and although I was much busier, I could feel my creative energy and curiosity return. I decided to try my hand at writing something like a mystery, and The Undercurrent, a novel about a new mother who becomes obsessed with story of a missing girl, arrived very quickly, as if it had been waiting for me to turn off the television and write.

A friend of mine, the very excellent writer Kate Hope Day, alerted me to a quotation by Benjamin Percy, in his craft book, Thrill Me: “…a good story is a turnstile of mysteries.” This idea makes sense to me: the reader must desire, need, to pass through one turnstile—one scene, one chapter—to get to the next. The joy of reading centers around this sensation, and the joy of writing is in creating stories that make the reader want to lean on that turnstile and turn the pages of your book.

But more importantly, the desire to move through that turnstile is the core of living. When the world seemed to stop in 2020, it was hard to remember to push on it and keep going. Now that the pandemic is limping its way into history and the election looms, it’s clear that we can’t stay on our couches and watch the world go by. It goes too fast, and it requires our loving, total participation.

The students at my school have returned to their business of living. I sit at my desk and watch them run out the door to catch their breakfast before classes begin and return at the end of a long day, sweaty and exhausted. They are sometimes joyful, sometimes angry, sometimes lonely, sometimes kind, sometimes cruel. It is all so ordinary.

What could be a greater mystery?

***