The most powerful piece of true crime–related art I’d seen in years was tucked away in a difficult-to-access corner of a downtown New York City museum. This was not what I expected at the spring 2022 New Museum retrospective for the artist Faith Ringgold, a formidable educator and activist best known for showstopper quilts that present visceral juxtapositions of major facets of Black American history.

The quilts were, justifiably, worth the museum visit. But my attention, at the time and since, kept returning to that corner, near a stairwell connecting the museum’s third and fourth floors, where the Atlanta Children and the paired Save Our Children in Atlanta and The Screaming Woman sculptures had been secreted away.

Atlanta Children, on the right, was structured as a chess board, but these were no typical pieces. Each depicted a Black child in distress or pain, or dead. On the left was a female sculpture (the aforementioned Screaming Woman) clad in a green dress, a button adorning her right lapel, holding a poster Ringgold had created listing the names of twenty-eight boys, girls, and young men. “This is a commemoration to all those wantonly slain in the dawning of life,” Ringgold wrote. “Make it impossible for the sins of hate and indifference to persist in America. Stop child murders!”

These words and images resonated as viscerally with me in 2022 as they must have with every person who has viewed them since their creation in 1981. Ringgold was making art out of the Atlanta child murders, one of the most confounding serial crimes in American memory, a story that resists the usual constraints of true crime storytelling—and yet inspired one of the foundational texts of this ongoing true crime moment, whose title and trajectory are in turn the inspiration for this anthology.

—

Black boys and girls were disappearing and turning up murdered in and around Atlanta. Between 1979 and 1981, as answers proved frustratingly elusive in tandem with the rising body count, parents of the murdered children demanded justice, because it was becoming all too clear there would be none. The subsequent killings of two men, Nathaniel Cater and Jimmy Ray Payne, both in their twenties, led to the arrest of twenty-three-year-old Wayne Williams, tied to their deaths by considerable circumstantial physical evidence. But even though police immediately named Williams as the prime suspect in the child murders—murders which appeared to stop with his conviction for the killings of Cater and Payne in 1982—he was never officially charged with those crimes. Larger issues grew more prominent in the intervening decades: Why hadn’t Atlanta police taken the child murders more seriously, and earlier? How had systemic inequalities, from asymmetrical economic status to homelessness and, above all, racism, influenced the trajectory, and the mistakes, of the investigation?

More than forty years later, after countless treatments in books, podcasts, documentaries, and scripted television series, the Atlanta child murders remain a cipher among criminal cases. The lingering lack of total resolution highlights how deeply the system failed the murder victims and their families. This is not, however, because of what remains unknown: it is because of what is known, is evident in plain sight, and still denied wholesale.

No wonder the celebrated writer James Baldwin felt called to explore the Atlanta child murders, first in a long essay for Playboy, and then in The Evidence of Things Not Seen, published in 1985, two years before his death. Baldwin was two decades removed from the height of his celebrity, when The Fire Next Time (1963) had made him the philosopher-king of the civil rights movement, whose work was supposed to bring order out of mounting chaos, and who was unfairly expected to alleviate white guilt and offer them hope as a salve.

But by the early 1980s, America had soured on Baldwin. Readers viewed his later novels and nonfiction as downers, as speaking truths that were no longer fashionable, no longer palatable, no longer a conduit for idealism. As Hilton Als wrote in 1998, “Baldwin’s fastidious thought process and his baroque sentences suddenly seemed hopelessly outdated, at once self-aggrandizing and ingratiating.” Backlashes against progress, and the rise of Reaganite Republican politics, prevailed. Baldwin still spoke in his own tongue, still called out the essential disparities. But younger generations found greater literary kinship with the works of Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Toni Cade Bambara. Searching for different truths blinded people to what was right in front of them: that Baldwin still had the fire, still was nowhere close to the end of the line.

This change in attitude about Baldwin may explain why the initial critical response to The Evidence of Things Not Seen was one of widespread bafflement. Baldwin had no interest in adhering to a typical true crime narrative, or even traditional narratives at all. His lambasting of the Atlanta Police Department and of the city’s governmental bodies was a song on repeated refrain, but most people just wanted to turn the music off. His reporting was introspective: while he did visit crime scenes and bore witness to the loved ones left behind, Baldwin ultimately concluded that he could not impose himself upon the parents of the murdered children after they had already suffered such grievous and continuing losses.

What baffled people then makes far more sense now in a society loosed from anything resembling order and of a consensus reality. The Evidence of Things Not Seen has rightly grown in stature over time, reconsidered as a forerunner for other important works that showed how crime is woven into the fabric of society, how the legal system is built to fail millions of the marginalized, and how prioritizing collective voices can supersede traditional narratives about perpetrators.

As Baldwin wrote in the book’s preface, the Atlanta child murders ultimately created a campaign of sustained terror, and because the totality of that emotion is so great, “terror cannot be remembered. One blots it out.” It is not the terror of death, but rather “the terror of being destroyed.” That palpable sense of fear permeates every interaction Baldwin has as he grapples, once more, with “having once been a Black child in a white country.”

It is not the evidence of what is unseen, but rather what society still refuses to see. When Lady Justice is willfully blind, how damaging are the costs and how irreparable is the harm? As both Faith Ringgold and James Baldwin knew too well, crime has always been a catalyst for greater pain, and no part of the pursuit of justice could alleviate it.

—

The past few years have borne perpetual witness to seismic changes that continue to rock the globe: the COVID-19 pandemic; protests against racial injustice, and then a vicious backlash; right-wing extremism and the cancer that is white supremacy; increasingly oscillating temperatures thanks to climate change; the obliteration of reproductive and LGBTQ+ rights; and the distortion of reality put in sharp focus by the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

Most of these major events were shocking, but surprises they were not. They were evidence of what was visible to anyone bothering to pay attention. Denial, however, is a more potent aphrodisiac than looking reality squarely in the eye. It is far easier to cast the perpetrator of a mass shooting, for example, as a lone wolf in the throes of mental derangement rather than a cog in the spinning wheel of more cohesive and reprehensible ideologies firmly rooted in bigotry and conspiracy theory.

True crime cannot be divorced from society because crime is a permanent reflection and culmination of what ails society. And while collective interest in true crime has only grown since the first season of Serial in 2014, so too has it morphed into something larger and more troubling, reflecting the acceleration of what we cannot look away from.

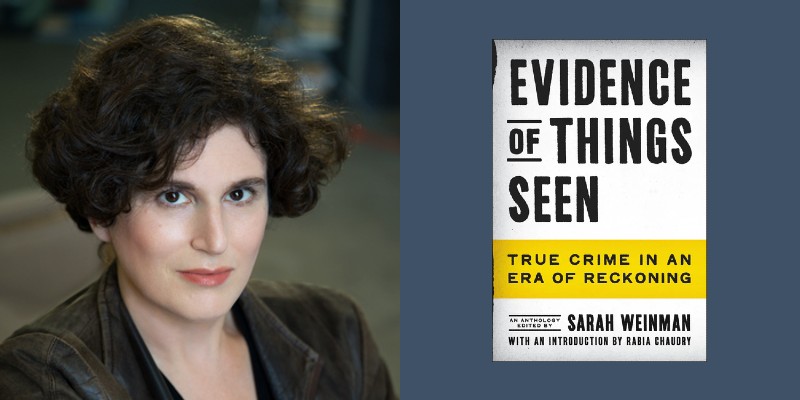

Evidence of Things Seen—of course the title is an homage to Baldwin, the Jeremiah of the latter half of the twentieth century—is divided into three parts. “What We Reckon With” examines events of the past few years, as well as the precipitating factors that catalyzed those events. Racial injustices past and present are examined by Pulitzer Prize winner Wesley Lowery in his searching portrait of a 1980s-era lynching, and by Samantha Schuyler, chronicling the brief life and murder of Black Lives Matter activist Toyin Salau.

Canadian writer Brandi Morin delves into the plight of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, specifically in California but universally applicable to North America, while Justine van der Leun investigates the continuing failure to treat as victims rather than perpetrators those who endure intimate partner violence and kill their abusers. White-collar crime, and the federal government’s steadfast refusal to punish those who engage in it, gets the full treatment by Michael Hobbes, and Atlanta merits the cruel spotlight once more through May Jeong’s powerful account of the city’s 2021 spa shootings, its effect on Asian communities, and the larger history of exclusion and xenophobia.

“The True Crime Stories We Tell” gives space to critical examinations of the genre and those who helped shape it. Amanda Knox takes back her own narrative and voice in unforgettable fashion, while Diana Moskovitz and Lara Bazelon convey the importance, complications, and damage done by the work of Miami police reporter and author Edna Buchanan, and Baltimore journalist and television showrunner David Simon. The ever-growing interdependence between true crime and those who consume it, and what happens when amateur participation becomes something more sinister, gets a full airing by RF Jurjevics.

The final section, “Shards of Justice,” offers some paths forward, both for our deeply fissured legal system and for the true crime genre itself. Amelia Schonbek examines a case of restorative justice with unbounded empathy, while Keri Blakinger, one of the finest criminal justice reporters working today, gives an inside look at death row prisoners finding solace and comfort in a radio station that’s specifically targeted to them. Sophie Haigney’s moving letter to the child of a victim of gun violence, whose death she witnessed, refracts and upends expectations, while Mallika Rao finds greater meaning, even hope, in an unfathomable murder story.

All fourteen of these pieces, as well as Rabia Chaudry’s incisive introduction, reflect true crime’s shift from providing answers to asking more questions. As a whole, this anthology is a testament to the discomfort we live in, and must continue to reckon with, in order to hold the true crime genre to higher ethical standards and goals. It is our duty to take the evidence of what we see, tell the truth, and strive for better.

___________________________________

From Evidence of Things Seen by Sarah Weinman. Copyright © 2023 by Sarah Weinman. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers