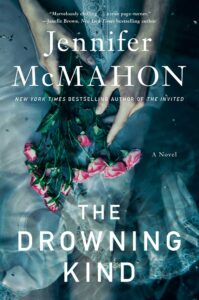

Recently, I was talking with a friend who was excited to hear I had a new book coming out soon. “But is it scary?” she asked apprehensively. I told her a little about it: a woman returns to her old family home after her sister drowns in the spring fed pool—oh, and the pool is rumored to be bottomless and her sister believed there was something lurking in the water. So yeah, it’s a little creepy. My friend apologized and said that she just couldn’t read unsettling books because of how unsettling the world is right now. I would argue (and did!) that that is exactly when we need these books the most; they take us to dark places and help us explore our fears from the relative safety of our favorite reading spot.

There’s no doubt about it: we’re living through some deeply disconcerting times; uncharted territory for us all. We are over a year into a pandemic that has led to millions of deaths and wreaked social, political, and economic havoc worldwide. It’s been devastating, life-altering, and downright terrifying. How am I—an anxious and frightened person by nature—coping? By reading terrifying books about bad things happening to good people; about evil spirits, the dead coming back to life, and monsters real and imagined. I’m re-reading old favorites like Frankenstein (more heartbreaking than terrifying, but still a deeply unsettling book), and the short stories of Shirley Jackson (The Summer People is one of my very favorites—the dark and deliciously creepy story of an older couple who dares to stay at their summer cottage past Labor Day). I’m discovering new favorites like The Deep by Alma Katsu, a terrifying twist on the Titanic story, and The Only Good Indians by Stephen Graham Jones—the Elk Head Woman scared the bejesus out of me and even now, weeks after reading it, I keep thinking I catch a glimpse of her out of the corner of my eye. I’ve even been revisiting some of my favorite apocalyptic novels as well: The Stand by Stephen King, The Passage by Justin Cronin, and my very favorite: Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel.

I was a fearful and anxious kid. My mother struggled with mental illness and alcohol abuse, and my biggest real-life fear was who I might find each day when I came home from school. Would she be Fun Mom, who’d make me a fluffernutter and want to hear all about my day? Drunk Mom, who’d cuddle up with me and weep about the pain of existence? Maybe I’d find her unconscious with empty bottles of pills and booze and have to call an ambulance. Or worse yet, she might just be gone, leaving no clue as to her whereabouts.

I was frightened of lots of other things too: mean kids, ghosts, half-human-half-beast creatures in the woods, kidnappers, big dogs. I spent many hours lying awake in the dark studying a small crack on my bedroom ceiling, convinced that something horrible was going to come crawling out of it. Nonetheless, I couldn’t get enough of scary movies and stories—I snuck my mom’s copy of The Amityville Horror (The thing I found most terrifying about it was that it said it was a True Story!) when I was way too young for it, and read it under the covers with a flashlight, wide-eyed with horror, but unable to stop reading. I’d invite my friends over for elaborately-plotted séances and ghost summonings, where I’d spook them to the point of hysteria. And of course, I loved to tell scary stories.

At the time, I didn’t think about why a scaredy-cat like me would be so drawn to things designed to make me even more frightened, or to frightening other people. But it’s obvious now that a lot of it was about giving me control of the horror. I could (though usually didn’t!), close the book or turn off the TV. I chose to go to the monster movie. And when I was calling the shots, whether writing a story about a haunted meatball for a 3rd grade creative writing assignment, trying to convince my little brother and his friends that a serial killer who’d just escaped from an insane asylum was on the loose in our suburban neighborhood, or ratcheting up the tension in a “totally true” ghost story told around the campfire, I had even more control over fear. It made me feel brave even though I was the opposite of brave. It gave me a rush because it taught me how to face the monsters and the darkness, take control, and come out alive.

That rush has stayed with me. Reading frightening stories tickles some part of our brain—perhaps the part that’s still holding onto that predator/prey must-survive instinct. It allows us to face danger and terror in a safe way. It’s contained and expected. You can take breaks and go at your own pace. You can turn on every light in the house and lock every door and window. You know that once you read that last page and put the book down, the story is over. (Though the best of them linger for some time after.)

Reading dark fiction brings us through such a wide range of emotions: prickling unease, terror, revulsion, deep dread, sadness. In facing our fears, we gain insight into ourselves; we learn what truly frightens us, how far we’re able to go before we’ve had too much. Maybe we also build our coping skills: I handled that—it was bad, but I survived.

There are so many beasts, villains, monsters, and yes, even viruses, that can’t be conquered in real life (or at least feel as though they can’t be conquered), but in horror fiction we get to conquer them. And on some deep level, it is a thrill to drag that thing lurking in your closet or under your bed out into the light and realize we can not only survive it, but face it, conquer it, maybe kill it once and for all (until the sequel at least…).

Scary stories can act almost like a manual for how to get through dark times: we walk alongside Stu and Frannie and the gang in The Stand, and battle plague and darkness and Randall Flagg; we see and feel good triumphing over evil, we know a new brighter day will come. In Station Eleven, we follow Kirsten and the Traveling Symphony, who have survived the downfall of life as we know it and are now bringing music and Shakespeare to a post-pandemic world, feeding the souls of survivors, as the painted sign on the lead caravan says: “Because survival is insufficient.”

Art survives, brings us strength, and carries us through; I think this includes horror fiction. It’s what gets me to my desk each morning to write, chasing my own fears on paper after listening to pandemic death tolls on the news, what makes me pick up the next novel I know I’ll get lost in. And you can bet it’ll be a creepy one.

***