If it was once possible to claim (as Cyril Connolly sneeringly did) that ‘there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall’, what does that make your iPhone? It’s easy to think of ways in which it—and the apps you’ve downloaded—make it harder to write than ever, what with the incessant temptation to doomscroll (thank you, 2021) and the ever-present lure of a quick endorphin hit from a Like or a Retweet.

At a slightly more serious level, any major sea-change in the way we all communicate also compels contemporary writers to think carefully about the way we tell stories—and about the kinds of stories that we choose to tell. This can happen in subtle ways as well as obvious ones. As the literary critic David Trotter has observed, the arrival of the telephone in middle-class homes in Britain during the 1920s and 1930s was accompanied not only by the arrival of the telephone as a plot device in British fiction but also an increased prominence in British writers as various as the comic novelist Evelyn Waugh and modernist novelist Ivy Compton-Burnett of conversations presented without context, of reproduced speech unaccompanied by descriptions of bodily gestures and with few clues to tone, as if the experience of attempting to communicate by words and voice alone, over the telephone, prompted a whole generation of writers to think about the pressures this places on language, the comic or poignant or revealing or suggestive effects which it can produce and which might be reproduced on the page.

Among the areas of writing in which the plot possibilities of the telephone were most quickly and effectively seized was the detective novel, and it remains the case that the narrative challenges posed and opportunities offered by modern communication tools are especially obvious for writers of contemporary crime fiction and thrillers. Since the invention of the iPhone—and the fact that with one in your pocket you are always contactable and easily traceable, ping ping ping—we have faced a dilemma. The first option? To think up an ingenious way to remove a functioning handset from your protagonists (stick them on an island a la Lucy Foley’s The Guest List, send them on a digital detox retreat like Lianne Moriarty’s Nine Perfect Strangers, or set your novel before the damn things were invented). The other option is to ask what new kinds of plotlines constant connectivity offers up—and to produce stories which help us understand what it means for so many of us to be glued to our phones.

One of the best early examples of social media being used to smart effect and in a ways that never overwhelm the story is in Caroline Kepnes’ You novels. In the first, You, published in 2014 (You Love Me, the eagerly-anticipated third book in the series is our later this year), she seized on the possibilities that these always-on networks offer, using Facebook and Twitter as a fuel for her protagonist’s obsessive behavior. “I was always astounded by social media. Suddenly, we have different ways of presenting ourselves and different platforms that bring out different aspects of us. We don’t have boundaries. We don’t lose touch without an active effort. These mental gymnastics are at the heart of Joe, because so much of You was about his inferiority complex. Social media pushes buttons in him, and that’s why it’s an integral part of the stories. Social networks are a dangerous place for a ‘sensitive’ man with obsessive, narcissistic, violent tendencies, and I use it in the books as both way for Joe to learn and an ever-present antagonist. One of the challenges I have found is that it is almost too much fun developing his online profiles—I could write Joe tweeting as various characters for 50 pages but those tweets had to function as part of the engine of the novel. A book is forever, so although I write about current communication styles, the challenge is to appeal to people in the future as well as people who don’t use social media. I track the emotional drive of the story to make sure we’re still going somewhere compelling in a good, old-fashioned storytelling way.”

Two comms-tech fueled phenomena loom large in this year’s crime fiction. First, podcasts—which, as an aural format are an interesting challenge for a writer as Eliza Jane Brazier, author of If I Disappear, explains.”The missing host at the center of my novel only interacts with the narrative through her podcast—we never see her on the page. So the challenge was to make sure that that character came through in a way that was not only realistic but emphatic. To do this, I interspersed podcast snippets throughout the narrative, so the transcript functions almost as the voice in the main character’s head. There are even scenes where the device becomes very meta and it is as if podcast host is telling us the story. So I definitely found fun ways to incorporate tech into the novel!”

In the upcoming The Murder of Graham Catton by Katie Lowe does a clever 180 on the idea of noble true crime podcast crusaders. Lowe explains the podcast’s huge appeal as a plot device: “I find it fascinating that glossy production values and a charismatic host can cover an abundance of sins. Most podcasts—especially those dealing with real crimes that impact real people—aren’t held to any journalistic standards and their reporting can spread across other platforms, into the traditional media, and then (in the case of my novel) back into the lives of the people who want to move on. The idea of making my podcast and their audience the novel’s antagonists, rather than heroic detectives and defenders of justice, was just too delicious to resist.”

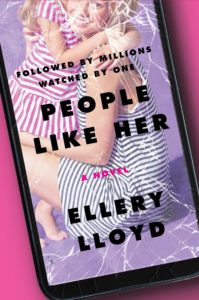

Then of course there is Instagram—specifically Instagram in the hands of someone who does it for a living—which is the focus of our own debut novel, People Like Her. A dark and suspenseful read set in the cut-throat world of influencers, it is narrated from three points of view—Emmy, a momfluencer who isn’t all she seems, Dan her washed-up novelist husband and a third, unnamed stalker, plotting a revenge on the family that is as intricate as it is vicious.

As a writing partnership, we spent a lot of time discussing how our novel might represent social media and reflect the ways in which our characters engage with social media, and the creative challenges and decisions that involved for us in writing our novel. Some were practical, some a bit more philosophical—anyway, these were some of the decisions we identified and wrestled with, as writers attempting to engage in a novel with the way we live online now.

Familiarity

Collette: Given a (hopefully) broad and varied readership, how much familiarity with any given aspect of internet culture can you assume? We came up with the idea for People Like Her after we had our daughter (we are a couple) and I fell down a scroll hole, spending more hours a day than is entirely advisable following in those little squares the lives of mums I’d never met and never would. Paul, on the other hand, had barely even heard of the app and has a broken hashtag key on his laptop. It made him the ultimate sounding board—do you understand what I’ve written and how it works given you’ve never used the app? How can you explain it simply without being patronizing—or boring? This is a tension you’ll often see on TV, when primetime mainstream crime series attempt to deal with online issues—and have to explain to each other, in terms you could understand if you had just been defrosted from thirty years’ hibernation, what a message board is, or how a dating app works.

Level of Detail

Paul: A question we kept asking ourselves was whether this was a novel about social media, or whether that was just part of the context. Because that raises the question of how much do you want, in your novel, about how this stuff actually works. And what might be the ways of introducing this information dynamically, so that it serves a plot purpose. And actually those are big questions for any author: what is the relationship between the story you want to tell and these enormous stories—technological or political or economic or social—that are going on in the world, that we are all aware of and struggling to get our heads around. But they are also quite specific questions on a sentence by sentence level: how much stuff do you want about scrolling, how much description do you want of people clicking and liking? The more used we get to new tech, the less you need to take the reader through the stages of using it. After all, if someone makes a phone call in a novel, you would not describe the process of picking the phone up, of dialing—but it was really quite recently thrillers would describe, in quite painstaking detail, the process of searching for some information online: ‘He cracked his fingers, and flexed his shoulders, and with a few swift strikes of the keyboard he called up his preferred search engine, Ask Jeeves.’

Everything Online Dates Immediately

Collette: On which note: The one thing that we absolutely know about communications tech—especially social media apps—is that the tech can change overnight. New features appear, old ones get retired, designs change. So don’t hinge your plot on some very specific aspect of a particular app, if you don’t want your novel to be immediately dateable—or dated.

The Moral of the Thing

Paul: Perhaps the aspect of writing a story featuring social media, and which is to an extent about social media, was to avoid finger-wagging. We’ve all read about the bad things social media does to our brains. We know it does not feel good, to stay up too late scrolling through pictures of people we don’t know, perhaps selling us stuff we don’t need and can’t afford in #ADs. Although we understand intellectually that the images we are seeing are carefully selected, and we are not comparing like with like, it still gives us a niggling, unfounded sense of our own inferiority. The biggest challenge writers face—and the biggest opportunity for the novel, as a form—is finding some way to convey that, and embody it, and help us consider what it might mean, that we know all of this and yet still do it.

In People Like Her we hope we have avoided some of the pitfalls outlined above. No doubt we have stumbled into many others. But these processes and pressures are not new to this generation of writers – one of the ways in which the novel has always reinvented itself, and moved forwards, is by incorporating and impersonating other kinds of writing: letters (see Clarissa) and travel writing (see Robinson Crusoe) and diaries (see Diary of a Nobody, see Bridget Jones, see Gone Girl) and emails (see Bridget Jones again, all those late nineties and noughties novels written entirely in emails). It is one of the ways that the novel not only keeps itself fresh, but also allows us to step back and take a careful, thoughtful, reflective look at the way we engage with each other, the ways we conceive of ourselves and present that to the world—and to really look at the language we use to articulate this, and the ways the stories we tell can bring it to life.

***