“A TRUE CLAIRVOYANT IS BORN, NOT MADE” read the all-caps declaration in The Indianapolis Star on March 5, 1911. Making this bold statement? “The Man from India.”

The claim came in a classified advertisement for Professor Stanley, a clairvoyant who practiced from North Illinois Street in the Indiana capitol city. Professor Stanley – who offered psychic readings for 50 cents – declared in his ad, “ONLY ONE STANLEY.”

“The only adept of Hindoo (sic) occult mysteries practicing in America at the present time,” the Man from India noted.

But what about Professor Sidney Elkins, billed as “The Man from India” in the Chicago Examiner on June 25, 1911? Elkins, whose readings cost twice what Stanley charged?

And what about Khiron, “The Man from India,” who – according to his Post-Dispatch advertisements – practiced from 3699 Olive Street in St. Louis in January 1911?

Stanley and Elkins each urged those who plunked down a nickel for the newspapers to “Read carefully” their promises to provide the most insightful psychic readings.

It’s a promise that helped the men stand out not only from all those other “men from India” but also from all those other clairvoyants, seers, mystics, mediums and psychics who promised to foretell the future and convince that they were “THE ONE PERSON IN THE WORLD who knows every secret wish of your heart, your every trouble, hope and anxiety and gives a solution in detail to all your past, present and future affairs,” as Professor Elkins phrased it.

All for a dollar or less.

The seers – another one, Santell, declared to potential customers that he was president of the Mediums World Association and had studied psychic research in London and “the Occult College of India” – had to distinguish themselves in some way from the hundreds of other clairvoyants who advertised in newspapers across the United States.

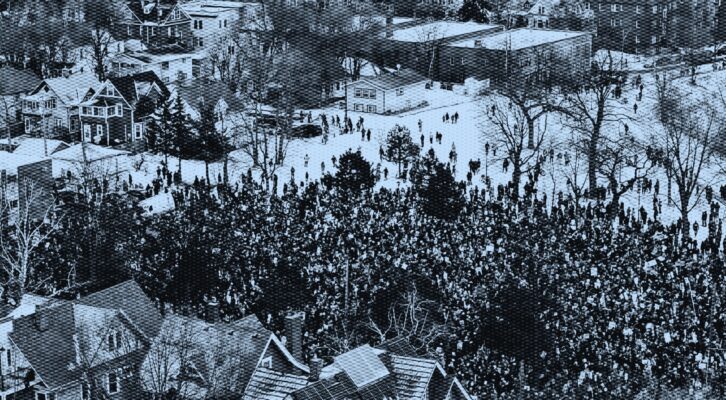

In many big city newspapers, a full page of the classified section was devoted to ads from clairvoyants.

In cities big and small, America in the early decades of the 20th century was captivated by psychics, seers and mystics.

Reaction to a frightening world?

There’s never been a time when any given point in the history of the United States was not called “a tumultuous time,” as the Encyclopedia dot com entry for the 1910s calls it.

But the period from 1910 to 1920 was a decade of innovations, like canned soup and Oreo cookies, as well as political turmoil in the years leading to the Great War, which would later be referred to as World War I. The decade ended with widespread deaths worldwide due to a flu pandemic first diagnosed among soldiers in 1918. Nine million people died in the war and about 50 million worldwide died from the flu.

Is it any surprise that the public would turn to mystics and seers to help them navigate what seemed like an increasingly frightening world?

The birth of spiritualism and psychic mediums in the United States has been pinpointed by Smithsonian Magazine to 1848 and Kate and Margaret Fox, two New York sisters who said they communicated with the undead through the medium standard practice of “table rapping.”

As interest in the spirit world grew, the Ouija board – which dated back hundreds of years to China – became popular in the United States after the Civil War, first as a tool for spiritualists but then for use in anyone’s parlor.

Belief in spiritualism rose in many quarters – there’s a spiritualist camp a few miles from where I live in Indiana and a similar spiritualist enclave is depicted in popular fiction like the crime drama series “Sneaky Pete” – and never really went away.

Edison, Houdini and Conan Doyle

Many people want another chance to speak with loved ones who are dead and gone and want answers to unfathomable questions, as promised by Professor Elkins and other clairvoyants and seers.

That need to reach out across the divide that is uncrossable by the living was felt by Americans famous, infamous and unknown. As president, Abraham Lincoln attended seances organized in the White House by his wife, Mary Lincoln, who hoped to reach her son.

Inventor and electric light developer Thomas Edison was apparently a believer in the spirit world. Edison wanted to develop a “spirit phone” that would receive the voices of the dead. He spoke to Scientific American about it in 1920 and even wrote about his wish in his diary.

It’s well-known, of course, that the escape artist and performer Harry Houdini spent much of the last six years of his life, leading up to his death on Halloween 1926, debunking stage spiritualists. Houdini was frustrated that he’d never been able to make contact with his departed mother, Cecilia Steiner Weisz, despite the promises of mystics that he would be able to. He exposed frauds and even, in 1926, testified to the widespread duplicity of seers in front of a Congressional hearing, unsuccessfully advocating laws against fortune-telling for money.

Although Houdini, starring in silent films, piloting aircraft and traveling with his own stage act of magic feats and escapes, would seem to have been sufficiently busy, in the 1920s he took on mediums and mystics in cooperation with Scientific American. The magazine offered a $2,500 reward for a psychic who could prove stage spiritualism was real.

This put Houdini, who was working with Scientific American, on a collision course with Margery Crandon, a popular mystic who amazed people at her seances. Houdini debunked Crandon to the magazine’s satisfaction, thwarting efforts to award her the $2,500.

Houdini’s exposes of spiritualists put him at odds with his friend, Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, who was a believer. Conan Doyle wrote a series of articles, published as the collection “The Edge of the Unknown,” in which he wrote about his beliefs and even postulated that his friend Houdini was not only the “greatest medium-baiter” but also “the greatest physical medium of modern times.”

Faith in the unseen was a hard thing to shake, even for the creator of literature’s best-known and most discerning detective.

Houdini’s wife, Bess, famously held seances every Halloween after her husband’s death to see if he could communicate from beyond the grave. She stopped the practice in 1936 after no mediums could provide the code phrase, “Rosabelle believe,” that she and Harry had worked out before his death.

Bess believed that if anyone could cross the divide between life and death, her husband would have been the one to do it. She gave up.

“Ten years is long enough to wait for any man,” Bess reportedly said.

‘Lemme hold that gold coin for a minute’

But all the debunkers in the world couldn’t dissuade someone whose philosophy was, as “The X-Files” said it on a poster of a UFO in Fox Mulder’s basement office, “I want to believe.”

One compelling argument for the value of clairvoyants in closing the book on a tragedy came in Indiana in the early years of the 20th century. In August 1909, newspapers reported the death of Lewis Stinglemire, whose daughter, Carrie, had been a domestic worker in the home of the president of Purdue University. The article recapping the father’s death noted that, seven years earlier, Carrie had gone missing.

A clairvoyant consulted by the father told him the young woman had jumped into the Wabash River and told him not only where to find her body but the condition of her remains. Stinglemire got a canoe and paddled down the river until he found his daughter’s body, exactly as the clairvoyant had said.

The day after the discovery, the newspaper reported, Stinglemire received a letter from his older daughter, who lived in Milwaukee. In the letter, she wrote that she had consulted a psychic who had also advised that the younger woman had jumped into a river.

As valued as clairvoyants were to some, others were skeptical. In a letter to the editor of a Muncie, Indiana, newspaper, a writer questioned why a clairvoyant would reveal to a customer the location of a gold mine or hidden treasure rather than just go get the fortune themselves.

The writer didn’t rule out the possibility of clairvoyance, but argued, “A real clairvoyant does not come to town and take out a column ad in the leading paper and flood the town with misleading handbills … I sometimes think the only real remedy is to let the ‘gullibles’ learn their lesson by bitter experience.”

Well before Houdini exposed many mystics, law enforcement responded to complaints from members of the public about times they felt cheated by clairvoyants.

In March 1912, police in Anderson, Indiana, began an investigation into “Professor” Andrew Larkins, a clairvoyant who was alleged to have swindled “more than a score” of people out of $20 dollar gold pieces.

Larkins had told his clients that it was necessary for him to clutch a gold coin during a séance “and the larger the piece of money the better.”

On the day he was to have returned the gold pieces, his clients went to his office and found a sign on the door that read, “Out of city, back in a few days.”

It was a development Larkins’ clients could not have foreseen.

___________________________________

Keith Roysdon is a lifelong reporter and writer whose experience dates to his days in high school. During his career, he interviewed Arnold Schwarzenegger, directors George A. Romero and John Carpenter as well as politicians and crooks galore, although his best conversation with a celebrity was one with Vincent Price just a few months before Price’s “rap” appeared on Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.” Roysdon has won dozens of first place awards in state and national journalism contests. He’s the co-author of three true crime books, the latest being “The Westside Park Murders,” and for CrimeReads he’s written about two dozen articles, including some about juvenile mystery books, author Dennis Lehane, noir films and true crime authors over the decades. He’s active on Twitter, although he’s often not happy about it.