When I fell in love with crime fiction, one of the first things I noticed was how crime writers love to evoke an exceptionally rich sense of place. Raymond Chandler’s mean-streeted LA. John D. MacDonald’s cynically despoiled Florida. James Lee Burke’s lush, lyrical, fallen Louisiana. The heroes’ worldviews in these books were so tightly wrapped up in their environments, it was impossible to imagine them being transplanted anywhere else.

What really got my attention, though, were certain stories in which very specific environments became something more—not simply expressions of their hero’s persona, but full-throated characters in their own right. Du Maurier’s malevolent Manderley, Stephen King’s accursed Overlook Hotel, or the brooding moor in The Hound of the Baskervilles.

I (like a few billion others) got hooked on Tana French in the first few pages of her debut novel, In the Woods. The dark Irish forest that opens the story hovers over it throughout, “all flicker and murmur and illusion … its silence a pointillist conspiracy.” Within a handful of pages we move to an archeological dig where the forest used to be, and from there into town and civilization—but the hero never really leaves the woods, and neither do we. When we finally meet the story’s villain, one of the creepiest sociopaths you’ll ever read, we get the queasy sense we’ve just come face to face with the forest itself, or its human incarnation. A slew of readers protested the story’s cryptic ending. I thought it was perfect—and that French had given us fair warning. All flicker and murmur and illusion.

Book #14 in the Reacher canon, 61 Hours, unfolds in a town called “Bolton,” a place bolted shut by a blizzard. A thick blanket of snow seems to suffocate not only Bolton but the story itself. Reacher develops an extraordinary relationship with a fascinating woman … that never escapes the confines of the telephone. He ends up in an underground maze of tunnels that transforms his enormous size, normally an unbeatable advantage, into a crippling defect. The story ends, uniquely among Reacher books, on a cliffhanger—our view of the actual concluding events obscured by that blinding snow.

I loved this stuff. Wanted to know, how do they do that?

And of course, like any magician’s apprentice, I wanted to try it myself.

A Ship that Bites

In Steel Fear, my coauthor and I threw our hero, the psychologically damaged Navy SEAL Finn (last name unknown), onto an aircraft carrier at sea with a serial killer on board. Our novel would be about what happens to people when they’re sealed up together in a tight, enclosed space. The USS Abraham Lincoln itself would be an agent of claustrophobia, a 90,000-ton “locked room.”

At least, that was the plan. But like human characters, I soon learned, these environments talk back. You start writing them thinking you’re in charge. You’re not. They are.

Our ship turned into a monster.

For most of the story, you don’t know who the killer is. All you know is that someone is taking the lives of the crew, one by one. And so it happened that the ship itself came to embody that malevolent force. Right in the story’s opening, you encounter the belly of the beast:

[Monica] began threading her way through the labyrinth. The nighttime safety lights provided her just enough illumination to see her way, their faint red glow giving the painted steel passageways an even more claustrophobic feel than usual. A lattice of wires, exposed pipes, and conduit brushed by overhead, like strands of web in a giant spider’s lair.

Gradually the Lincoln becomes more threatening. Here is a jet pilot’s view as she attempts to land her F/A-18 Hornet on the flight deck at midnight:

The boat heaved, bobbing up and down in forty-foot swells, the enormous brass propellers visible for a few seconds at a time, the monster baring its teeth.

The AC system fails, is fixed, fails again. An outbreak of food-borne bacterial illness sweeps the ship, sending sailors by the hundreds through sick bay and back to their racks. Nerves are stretched. Fights break out. In the climactic sequence, the ship’s entire lighting system goes on the fritz, plunging the scene into darkness.

It’s possible, just possible, that at some point in the story those brass teeth will actually eat someone.

A Conflicted Personality

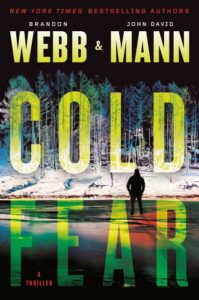

For the sequel, Cold Fear, we put Finn in Iceland—cold, gorgeous, violent, majestic. In the prologue a young woman steps into a pond at the center of Reykjavík, slides under the ice, and drowns. Why, no one knows, and that great sheet of ice and rock that is Iceland ain’t saying.

“Today the city was a ghost of itself,” Finn observes, “streets deserted, its buildings like bones of the long departed.”

But Iceland, too, refused to sit still for its portrait. On the page it soon began revealing not its silent grandeur but its inherently contradictory, torn nature.

It was an eerie mix of old and new, a mash-up of Heidelberg or Prague or some other quaint European burg with a futuristic scene out of Final Fantasy … a medieval village on an LSD trip.

And it is a self-conflicted nature that goes bone-deep:

Sitting astride a seismic fissure between the two tectonic plates that held North America and Eurasia, the entire country was split in half along the diagonal, like a cut lunchbox sandwich, its two halves pulling apart by another inch every year.

“Iceland,” as the dour cop Krista Kristjánsdóttir notes, “had the broadest social net in the world, the most generous health-care system. A paragon of equal rights and social justice, rated the safest country on earth. So why did so many Icelandic men still beat their women?”

Late in the story another character explains it this way:

Iceland is a child who has reached the age of majority and come suddenly into a trust fund. Yesterday she was playing with trolls and sheep-bone toys, today she is driving her friends in a Maserati at 150 kilometers per hour. But she is still a child, trying to grasp what it means to be an adult.

Finn, too, is being pulled apart “like a cut lunchbox sandwich.” Is he a hero or a villain? He has a memory of saving his first life, a drowning boy, at the age of 15 … but now he questions that memory. Did he actually let the boy die?

Iceland may hold the answer—but if so, it’s in no hurry to tell.

***