In 1976, Roger Allen Jaske was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison by the Superior Court of St. Joseph County in South Bend, Indiana. According to Jaske, he and another man had gotten into an argument, prompting the other man to pull a knife. Jaske claimed that he disarmed the man, then used the knife to stab him in the struggle which ensued. Court records note that Jaske also choked the man, tied him up, and left him to die in the woods, but upon returning for the ropes, discovered him still alive. Jaske stabbed the man several more times, discarded the knife, and stole his wallet to make the incident appear to be a robbery.

A decade later, in March of 1986, eight men were charged with conspiring to help Jaske escape from Indiana Reformatory, a state prison. According to authorities, some of the men were recruited through an advertisement in Soldier of Fortune magazine, which had offered them $10,000 each, as well as reimbursement at double the cost of their expenses, plus connections to more “contracting” work in the future. Defense lawyers argued that, yes, the men were lured to Indiana from as far away as New York, Alabama, Texas, and Colorado with promises of wealth and adventure, but they did not realize that they were being enlisted to break a murderer out of prison.

To me, at least, that was the truth. I know, because I was one of the defendants.

***

In 1986, I was 21 years old and serving in the US Marine Corps Reserve in New York. I grew up in Long Island and enlisted after high school simply to face the challenge of becoming a Marine. I had initially enjoyed serving, but my experience in the reserves was becoming monotonous. At the time, I had been regularly purchasing Soldier of Fortune for about a year. Founded by a former Vietnam veteran, the magazine included reviews of various weapons and military gear, along with classifieds that occasionally offered contracting opportunities for individuals with prior military or police training. I was paging through the latest edition when I came across the ad:

Mercenary looking for male Caucasian partner, age 18-25. Willing to accept risk. Must have guts, be able to travel, and start work immediately. No special skills required. High pay guaranteed. Ask for Sundance.

Contacting the number listed put me in touch with Richard Alery. Our first discussion was surprisingly reassuring. I was skeptical and had a lot of questions, but Alery was very polite and said all the right things. He and I spoke a few more times over the phone, during which I expressed my interest in abduction recovery scenarios, contracting and bounty hunting work. A year earlier, religious fanatics poisoned more than 700 people in Oregon, bringing my attention to the plight of children trapped in cults, whom I hoped to help. I felt that it would be a noble calling, helping children, and Alery assured me that plenty of opportunities were available. He invited me to meet with him to discuss things further in person, at a Motel 6 in Anderson, Indiana, where I was supposed to ask for the “Tom Johnson” party.

I planned to stop at home to change out of my uniform, then take the Long Island Rail Road to Penn Station in Manhattan, Amtrak to Indianapolis, and a taxi to Anderson. In my excitement, I had brought a fellow Marine into the fold, who was set to come but had to back out last minute due to another obligation. That Friday, I coincidentally received a promotion in the Marines; a few hours later, I left for Indiana.

***

Anderson is a small city in central Indiana, just northeast of Indianapolis. I checked into the Motel 6 there at 9 PM under the “Tom Johnson” party and immediately began to feel uneasy. All I could think of was how it didn’t feel right to be there. I called Amtrak to find out when the next train back to New York was leaving from Indianapolis and learned that it would be the following day, at 11 AM. I set my alarm for 6:30 AM and went to bed.

Not long after, there was a knock at the door. I let two men into my room, one balding and wearing a tie dye T-shirt with jeans, the other dressed more casually, with dark hair and a mustache. The first asked if I had a weapon and whether it was loaded (I did, unloaded, legal, and packed away), while the second laid a crudely drawn map of a courtroom out on my bed. They said “it” would go down in the morning and asked if I was in. I was exhausted from traveling, nervous, and considering my options to get out of there safely. I wanted to stall, make up a story about needing to do a dry run. I was hoping that if I could put everything off, I would still be able to catch the 11 AM train back to New York and pretend like I had never even seen the ad in Soldier of Fortune.

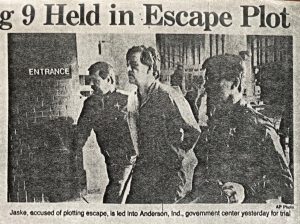

But before I had the chance, one of the men was pointing a gun at my face, telling me that I was under arrest. They were both officers with Anderson Police Department, and I was being accused of conspiring to break a man out of prison whom I had never even heard of: Roger Allen Jaske.

I was booked at the Madison County Jail in Anderson and interrogated into the early hours of the morning. I cooperated fully, though I still didn’t understand why I was being held. I wasn’t given a phone call, didn’t ask for an attorney, voluntarily submitted to a handwriting analysis, and even offered to take a lie detector test. Afterwards, I was escorted to H block, cell 261. The walk felt like it was in slow motion, my only sense that of hearing my footsteps against the commercial-grade linoleum tiles and the hum of the fluorescent lights. The sound of the door locking behind me after I entered my one-man cell was surreal.

I just sat there, handcuffed. Eventually an inmate from another cell asked, “What the hell did you do? They never left anybody in their cells with the cuffs on before.”

***

The details of what I had become wrapped up in only became clear to me over the following weeks:

In 1983, while serving his life sentence at Indiana Reformatory for his 1976 murder conviction, Roger Allen Jaske killed again. Court records describe Jaske subjecting a fellow inmate to an “initiation” by tying his hands and feet, blindfolding him, and punching him repeatedly in the stomach, eventually knocking him unconscious. Jaske attempted mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, but refused to seek medical attention. Instead, he buried the man’s body on the grounds of the Reformatory, where it was eventually discovered. Medical testimony found the cause of death to be “blunt force injury to the abdomen with tearing of major vessels and hemorrhaging.” Jaske was charged with manslaughter and scheduled to be tried in March of 1986 at the Madison County Circuit Court. The courthouse was only a 10-minute drive from the Motel 6 where I was arrested.

According to law enforcement, Jaske and Richard Alery—the man whom I had first spoken to on the phone—concocted a plan to break him out of prison during that trial. Alery was to storm the courthouse and hold its employees hostage, but needed help, hence the ad in Soldier of Fortune. Jaske’s aunt unknowingly took 50 calls responding to the ad, which she forwarded to Alery. After learning that the ad was in reference to a prison break, one respondent tipped off the Indiana Reformatory, leading to my arrest, along with six other men who had arrived at the Motel 6 on Alery’s instruction. Alery testified during the trial that he backed out after learning the plot involved the taking of hostages. Court records state he left an envelope, which included plans for the escape at the motel’s front desk and returned to Minnesota where he was arrested the following day. Some had experience tangential to the military, like the Army helicopter instructor, but others were just loners, one arriving in Anderson with the car he lived out of, two BB guns in tow. Altogether, nine people—Jaske, Alery, myself, and the six others—were charged with conspiracy to commit escape. We were all to be tried together.

My family first learned of my arrest the following day, when a fellow inmate called them on my behalf. Their initial reaction was one of shock and disbelief, but they just wanted me home. They hired a private investigator and a lawyer for the trial, which would begin in July. Until then, I just had to hold strong in Madison County Jail.

***

Throughout most of my time at Madison County, I was in H block, cell 261. The jail itself was run well, the guards fair and professional, and the inmates generally agreeable. There was only one significant incident that I had with a fellow inmate, who kept trying to get me into his cell during lockdown to “read the Bible.” He didn’t come across as a Bible-reading man and was, in fact, serving 40 years for rape, deviant conduct, and confinement. One day, this inmate stepped on the big toe of my left foot, which had been severed and reattached after an accident with a lawn mower when I was 16 years old. Instinctually, and before the guards could react, I slammed the man to the floor. From then on, he left me alone.

My first months at Madison County were the most psychologically trying. I did not, nor would I ever, willfully be part of the things that I was being accused of, yet I was being charged, held, and tried for just that. I felt wrongfully imprisoned and increasingly hopeless as the months dragged on. My desperation peaked when, after collecting 22 pain relief pills, I contemplated swallowing them altogether to attempt suicide. Thankfully the notion passed, and I flushed them all. I was mortified of the situation I had stumbled into, but I was going to see it through.

After that, jail became as easy as I suppose it can ever be. I threw myself into physical exercise, my work assignments, and the eccentricities of incarcerated life, such as learning to tattoo with a wire and a burnt paper cup, and making “pruno,” or prison wine. I adjusted well enough that the warden asked me, for a second time, to become a “trustee,” which came with privileges that my cellmates encouraged me to accept. I worked in the laundry and then the kitchen. Along with the chaplain, I delivered Bibles to local parishes on two occasions. I was even granted two eight-hour unsupervised releases to spend with my family, who took me to a local state park, a gym, and, unbelievably, Red Lobster.

Things were more bearable, but I was still in prison. One day I came across an inmate who had sliced his wrists with a blade that he had secretly removed from a shaving razor. Blood was everywhere. I couldn’t tell if he was alive or dead.

With each passing day, my own court date was approaching, which would determine how much longer I would still be there.

***

At Madison County Circuit Court, it felt like some of us were being thrown under the bus, at least initially. Even after accounting for public safety, those of us without prior histories should have had an opportunity to post bail. Alery had actually been transferred into my cellblock at Madison County Jail, but I ignored him completely. Just like on the phone, in person he was very polite, almost submissive, and actually apologetic for misleading me. Jaske, on the other hand, I saw only in court. He appeared to be cold blooded, completely institutionalized. The rest of my co-defendants were all modest, unfitting of the crimes we stood accused of.

The entirety of the trial lasted three weeks. Each day, I would be brought into the courtroom and just sit there, riddled with anxiety, disbelief, and embarrassment. Due to my state of mind, I don’t even recall the judge who presided over my case or the jurors who were to decide my fate. The prosecutor, on the other hand, stood out as being overly invested in the case and trying desperately to make the absurd charges stick. Thankfully my defense lawyer was both charismatic and thorough.

Despite all of us defendants being tried together, it was plain that we were not equally complicit. Alery and Jaske were directly implicated by the person who had tipped off Indiana Reformatory, leading to our arrests, as well as another former inmate whom Jaske had tried to enlist, but who instead turned informant. Alery implicated one of the other defendants, saying the man knew about the prison break, but otherwise testified that he and Jaske had recruited the rest of us without ever divulging their plans. In the end, there was little tying me to Jaske’s plot besides my answering the ad in Soldier of Fortune.

Notwithstanding my innocence, I was having intense anxiety. Truth be told I was extremely shy at that age and just the thought of having to testify on my own behalf was terrifying. I was ultimately spared that ordeal, but just the fear of it was taking a toll. One day I had to be rushed out of court to the hospital, as I was experiencing crippling abdominal pain that turned out to be induced by anxiety.

After the closing arguments, the jury deliberated the case over three days. I sat in my cell and felt overwhelmed to the point of becoming completely detached. I didn’t consider the possibilities, one way or the other. I didn’t think of my family, though I’m sure they would have supported me in an appeal, if necessary.

On Saturday, August 9, the 12-person jury handed down their verdicts. Jaske, Alery, and one other defendant were found guilty of conspiring to commit escape. Three other defendants were found guilty of carrying handguns without permits. And the three final defendants—myself and two others—were found innocent of all charges.

***

I was released from Madison County Jail the following day. The guards walked me from my cell to collect my personal belongings and say goodbye to the people on my cell block and some of the staff. The first person I saw was my mother, who was ecstatic. We walked out of the jail together to meet the early morning sun. We went to breakfast with my father, brother, sister, lawyer and private investigator, who invited us to his lake house, where we spent a day before returning to New York.

Altogether, my release had the air of a joke about it. My family had greeted me with a commemorative T-shirt that they had made reading, “I Survived Anderson 8-9-86.” Some of my co-defendants autographed other specially printed T-shirts for the sheriff’s deputies and inmates which read, “I Survived the Courthouse Commandos.” The front page of The Indianapolis Star described my co-defendants and I as “mercenaries”—with the quotation marks.

Early on my parents hired a private investigator who reached out to my friend (the fellow Marine and who had to bail last minute). This person knew of my desire to obtain legitimate contracting work. He had spoken to Alery on the phone at one point and could have corroborated the fact that we had no idea in regard to a planned escape or anything illegal for that matter. My mother arranged to have a court stenographer come to our house to record his testimony, but he never showed. Mind you, this person was my friend, he’s been to my house before, and my family was fond of him.

I didn’t find out until after my release, but it turns out that my friend had been accepted into Army warrant officer school and was reserved a spot in the Apache helicopter pilot program. A close mutual friend told me that his father pressured him to stand down to avoid possible complications.

Soon enough I was on a flight back to New York, where I looked forward to piecing my life back together and to my commitment with the Marines. My mother had kept my commanding officer filled in about my situation, so while there were of course some question and the initial wall of embarrassment, life otherwise continued as if nothing at all had happened.

A week after my release, I decided to meet a friend for a celebratory drink. I arrived at the bar to find him with a producer, who wanted me to sell him the rights to my story. He had a contract on hand and was offering me, once again, $10,000. Thankfully, this time I had the good sense to pass.