An hour and forty minutes into The Irishman, we witness the brutal shooting of 48-year-old mobster, Joe Colombo Sr., at the hands of a Black man on June 28, 1971 in the summertime streets of New York City. Seconds before the three shots were fired, Colombo walked towards the Columbus Circle stage to deliver a speech at the Italian-American Civil Rights League rally. As the founder and leader of the organization and event, The Unity Day gathering was a massive occasion decorated with green, white and red banners that represented the Flag of Italy, while actual flags were waved by proud Italians of every age and class. It looked as though the Feast of San Gennaro had moved uptown for a day. There were numerous vendors selling food and souvenirs as entertainers performed in front of a crowd of thousands. Across the street was Central Park and, a few feet away, the Paramount Theater was showing The Hellstorm Chronicle, a documentary about insects and the end of mankind.

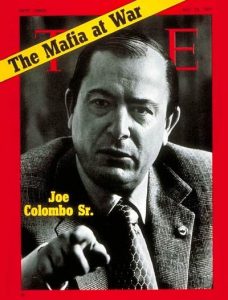

The festivities kicked off at noon and the place was packed. Some say there were 150,000 people present while other claim it was more like 5,000. Still, whatever the amount, there were a lot of New Yorkers gathered near Central Park to hear Colombo’s message about the supposed mistreatment of Italian-Americans at the hand of the federal government and the entertainment companies that, he believed, viewed the decedents of the boot-shaped country to be Cosa Nostra or Mafioso. Never mind the fact that Colombo was the head of a powerful crime family, one of the Five Families that ran New York, he wanted the rest of the world to think that it didn’t exist. In 1971, he even had The Godfather producer Albert S. Ruddy remove the words “Mafia, Cosa Nostra and Mafioso” from Francis Ford Coppola’s breakthrough feature before giving the film the Italian-American Civil Rights League seal of approval.

Joe Colombo had already made enemies within the other crime families, because the league was bringing too much public scrutiny to their business. Colombo relished his role as well as a public figure, and gave numerous interviews which included an appearance on The Dick Cavett Show two months before the shooting. Still, as we see in The Irishman, the attempt on his life was the beginning of the end for a lot mob guys. “I don’t believe that crazy bastard thought he could do that right there in front of 5,000 people and get away with in,” Russell Bufalino (as played by Joe Pesci in The Irishman) says to Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro). “That is a total piece of shit, that’s a piece of shit.”

Watching the scene, I wasn’t sure if Bufalino was referring Crazy Joe Gallo, the gangster, who in The Irishman was played by Sebastian Maniscalco, many thought responsible for the hit, or the shooter, a young Black male with a medium-length Afro wearing a light colored shirt and holding a 7.65 automatic inches from his intended victim. In the Martin Scorsese flick, the director filmed the scene in slow motion as the young Black man who blasted Colombo as blood sprayed from his head and chest as people screamed.

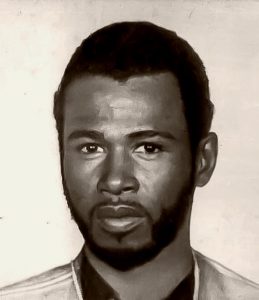

According to an overwrought Life magazine story, “Colombo collapsed at the foot of the statue of Christopher Columbus, grievously wounded with three bullets in his neck and head.” The same piece referred the shooter as having been “arrested at least seven times, had been known to terrorize women, to fawn over guns and machetes and to save photographs of Adolf Hitler.” However, unlike many of the other bad men depicted in the shoot’em up The Irishman, the gunman’s name, 24-year-old Jerome A. Johnson, was never mentioned.

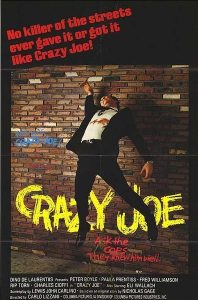

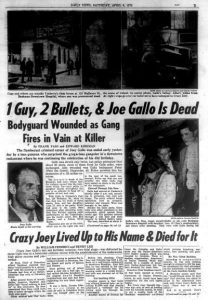

Because the shooter was Black it was assumed that Joe (Crazy Joe) Gallo, who had become chummy with Harlem hood Nicky Barnes and other African Americans gangsters when he was locked-up Green Haven Correctional Facility, set-up the hit. Crazy Joe, who was slain on his birthday (April 2) the following year, was a well-read gangster who favored Camus and Sartre, had had a song written about him by Bob Dylan and, two years after his death was played by Peter Boyle in the 1974 movie based on his rise and fall; a character based on Nicky Barnes was named Willy Bates and played with swagger by Fred Williamson.

It was never proven that Jerome Johnson was connected to Gallo, but someone on the inside got him the press pass that enabled Johnson to pose as a reporter at the Unity Day celebration. Carrying a 16 mm Bolex film camera that he’d rented in Cambridge, Massachusetts the weekend before, he explained to friends in New England the he was going to make a documentary about America after the Vietnam War. He left Cambridge on Sunday, June 27th, a day before the shooting, with a white woman, the camera and a monkey in a carrying cage. He’d supposedly bought the monkey on the street as a present for his Massachusetts hostess, but when she rejected the gift, Johnson brought the hairy beast back to New York.

Some news outlets reported that Johnson was a “crazed, lone gunman,” but there were people that saw a Black woman accomplice working with him. To pull off the reporter ruse, Johnson was equipped with both film and still cameras. New York Times reporter William E. Farrell interviewed Carl Cecora, a 30‐year‐old rally captain, who told him, “I was standing by the fence and Joe was talking to everybody. This colored girl came up to him and said, ‘Hello, Joe.’ And he smiled and said, ‘Hi ya.’” “She was with a guy, a colored guy taking pictures, and they asked Joe to pose and everyone to spread out, and before you know it, the shooting started.”

Although the camera was in his hand and the gun was in the case, according to New York Times reporter Barbara Campbell wrote in a story published on August 2, 1971, “The police have not explained how Johnson got rid of the movie camera in those final seconds, while Colombo was moving away, and then shot him.” Moments after Johnson fired on Colombo, he was gunned down even though he was already in police custody and surrounded by the cops. Both the unnamed woman and Johnson’s shooter somehow fled the scene, and neither was ever found.

The camera case was retrieved and inside were four certificates from the National Rifle Association attesting he was “a marksman and sharpshooter.” Chief Albert Seedman later told reporter Fred Ferretti, that he thought Johnson took the certificates along with him as credentials “to convince those who hired him that he could do the job.”

The day after the incident, The New York Times reported: “One of the policemen near Colombo was Deputy Chief Inspector Thomas Reid, who said he heard “two shots—maybe three,” and along with other policemen pounced on “a black man with a gun.” “It was all over in a matter of seconds,” Inspector Reid said. “I saw a hand sticking out with a gun and I jumped for the gun.” “A shot went off,” Inspector Reid said, “we were holding on to his hand—I don’t know who shot the black man.”

In 2016, Joe’s son Anthony Colombo told Mafia aficionado and author Ed Scarpo (Inside the Last Great Mafia Empire), he believed the F.B.I., not gangsters, were responsible for trying to kill his father. “Would (Jerome) Johnson or anyone else believe that the Gallos had the influence to get Johnson out (of Columbus Circle)? It’s not plausible. Who would Johnson believe could slip him away and cover it up? The Gallos or law enforcement?” Johnson’s killer was never caught or identified, though the F.B.I. suspected Colombo bodyguard Philip Rossillo as the killer. He was later brought in for questioning and released.

After the shootings, Colombo was rushed a few blocks away to Roosevelt Hospital. After several operations and a stint in a coma, Colombo was brain damaged, but he lived for another seven years. He finally expired on May 22, 1978. The Italian-American Civil Rights League, however, died that day at the marbled feet of Columbus.

In Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires author Selwyn Raab wrote, “Four hours after the assassination attempt, a caller to the Associated Press, identifying himself as a spokesman for the Black Revolutionary Attack Team (BRAT) said Colombo had been shot in retaliation for violent acts committed by the white power structure against African-Americans. Detectives soon determined that the group was fictitious.”

Two weeks later, Jet magazine debunked further the Black radical story. “A close friend of Johnson’s who identified himself to New York police as “Ken,” denied that Johnson had any militant contacts. He claimed that Johnson was scheduled to leave the country for the islands after he made a big score.”

The same article showed a photo of Sammy Davis Jr. and his wife Altovise leaving Joe Colombo’s hospital room. What Jet failed to mention was that Johnson, according to writer Raab, “mixed mostly with whites and detectives were unable to find a single black friend of his.” Including the woman that was supposedly with him the day of the shootings.

In the forty-eight years since Johnson’s death, I’ve revisited the story of the New Brunswick, N. J. native that, in addition to being a son and brother, he was a rapist, con man, bad check passer, woman beater, pornographer, pimp and movie producer.

There were several layers of crime stories woven in the bloody Joe Colombo/Jerome Johnson scenario, but, for many folks watching the footage on the six o’clock news, the main mystery became, who was “the colored guy” and why did he try to kill Colombo? Certainly, I can remember being an eight-year-old New York City boy watching channel 7 anchorman Roger Grimsby report the incident on Eyewitness News and, as a fan of every cop show on television, was also curious, though it would be years before research led me to the tangled web life of Jerome Johnson.

In the forty-eight years since Johnson’s death, I’ve revisited the story of the New Brunswick, N. J. native that, in addition to being a son and brother, he was a rapist, con man, bad check passer, woman beater, pornographer, pimp and movie producer. Over the years I’d thought about adapting his short, sordid life into a novel length text called Soul Assassin, but each time I abandoned the idea. However, watching The Irishman brought the memories of those New York mob days rushing back as well the small role Johnson played in the drama.

* * *

Jerome A. Johnson has been described as “emotionally disturbed” by Life magazine, “slow-witted” by authors Bert Randolph Sugar, C. N. Richardson and a “black street hustler” by The Villager journalist Lorenzo Ligato. While I have no idea how any of these sources came to their conclusions, based on my own research he did have serious issues that included rabid misogyny and an admiration of Adolf Hitler.

In his lifetime, Johnson unsuccessfully tried to procure women and become a pimp, and was also involved in gay pornography with Michael Umber who operated at mob run homosexual bar that Johnson frequented called Christopher’s End that was “controlled by Paul Di Bella, a soldier in the Gambino family.” In a July 20, 1971 New York Times article Police Chief Albert Seedman said, “Johnson frequented the Christopher’s End in the weeks immediately preceding the shooting.”

The bar, located on Christopher Street and the West Side Highway, was a few blocks away from the legendary Stonewall and shared the same address with Christopher Hotel, a five‐story building for transients that was also owned by Paul Di Bella. It was initially believed that the hotel was Johnson’s last residence; the police announced that his last known address was a dilapidated storefront in an Italian section of lower Manhattan at 176 Elizabeth Street.

At the police news conference on July 1, the police said they had found the monkey Johnson brought back from Cambridge, Massachusetts at the Elizabeth Street address, along with some of Johnson’s possessions, including a box containing cartridges that fit a 7.65‐mm. automatic pistol. Though Johnson used his mother’s (Mrs. Ethel Johnson Smith) home at 88 Throop Street in New Brunswick as a mailing address, he sometimes stayed at that Greenwich Village hotel.

Chief Seedman believed it was the Gambino’s, not the Gallo’s, who were behind the Colombo hit, but brought in the leaders of both families, Carlo Gambino and Joe Gallo, for questioning. In J. R. de Szigethy’s brilliant and detailed AmericanMafia.com article Who Shot Godfather Colombo? A Special Report: On the 40th Anniversary of an Historic Mafia Milestone, he went deep into the case revealing that Umber also pimped underage boys to wealthy pedophiles and had originally hired Johnson as a cameraman for gay porn movies.

While The New York Times articles made no mention of Johnson’s debauched and illegal activities with Umber, on June 30, 1971 they reported his deviant behavior towards women that began with the self-proclaimed “Pisces Man” who used to hang on the Rutgers University’s campus in New Brunswick. Campus detective James Wolfe described Johnson as a “spellbinding conversationalist” who constantly talked about astrology and cameras, focusing his attention mostly on young white women. Described as a natty dresser, Johnson was charming until he wasn’t.

When Johnson began to display his creepy true colors, his behavior scared the coeds. One woman, who refused to give her name, told a journalist that Johnson passed himself off as a lawyer, tried to help her with a minor police matter and then moved himself into her home: “One day he showed up at her apartment, she said, and that was the start of ‘three months of torture.’ From time to time, she was beaten and raped, the woman said, and threatened with an ax, machete or sword. The woman, who said detectives had interviewed her, told of Johnson’s talking into the night, contending he was God and admiring Italians.”

In 2011, B-movie/television director Guy Magar wrote in his autobiography Kiss Me Quick Before I Shoot that he met Jerome Johnson, whom he refers to as JJ, during his last semester at Rutgers in the spring of 1971. Magar had recently finished his first film when a friend introduced him to Johnson who told the student he was going to hire him to direct a feature starring his “good friend Diana Ross.” Magar, who shared an apartment with his roommate Theo, didn’t suspect anything even when the producer began crashing on his couch, puffing up all the pot and eating his food.

“One day,” Megar wrote, “JJ announced that he was setting up a press conference to launch ‘our movie’ and that he was going to have the star of ‘our film’ fly in on a private helicopter to attend this media event. Stunningly, he then announced this star was none other than his good friend Diana Ross! Yup, the legendary diva star of The Supremes. It don’t get better than that! Our Jerome then talked the city of New Brunswick into providing a meeting hall to hold this media bash, and he made a deal with a caterer to provide an elaborate food spread for the event. He even hired a pianist to create an elegant mood. Jerome used my typewriter (remember those?) to write his press release to local and state media folks to announce the launch of a new movie…it was certainly a day I will never forget.

“Jerome looked sharp in a tan suit and tie, and was expertly blah-blah-blahing a mile a minute to all the entertainment reporters who showed up with video cameramen in tow. There were about 50 people at the press conference and JJ went on and on about the movie, its unprecedented commercial potential, and his beaming new director discovered from—of all places—the Rutgers philosophy department! He just kept talking while checking his watch, wondering what could be keeping his dear friend Diana from arriving.” Of course, Ms. Ross never showed-up and Megar realized he was being used. He cut ties with Johnson, who left promptly and without a fight, but two months after the great feature film fiasco, Johnson shot Colombo.

“The next day,” Megar noted, “as I sipped my morning coffee, I read the front-page article about the shooting. The newspaper featured a mug shot of the dead assassin, and later the police photo was broadcast on every TV newscast. To my shock and amazement, I saw that Colombo’s assassin was a black man (unusual in an Italian mob hit) and I instantly recognized him! It was my very own couch moocher, my angel film producer, the now-revealed ex-con hired by some mob boss to assassinate another mob boss! He was the best movie hustler I ever met. And the dumbest assassin ever born.”

* * *

Forty-eight years later, through the mythology machinery that produced Martin Scorsese’s latest gang bang, I was reminded of bad man Jerome Johnson as I wondered what wild ideas went through his young mind when he accepted the suicide gig to kill Joe Colombo. Did he really think he would escape and zoom to the islands or, did was he paid in advance and gave the money to his mother for a new house. The friend he stayed with in Cambridge, Massachusetts told The Times Johnson wrote a lot of checks, and seemed “to have money and not have money.”

Six days later, a hundred people, including his weeping mother and Air Force serviceman brother Myron, were gathered at Anderson Funeral Home in New Brunswick for his homegoing.

Returning to the city that Sunday, Johnson contacted another friend who told reporters that the usually “easygoing” man seemed nervous. Six days later, a hundred people, including his weeping mother and Air Force serviceman brother Myron, were gathered at Anderson Funeral Home in New Brunswick for his homegoing. Lying inside a simple gray coffin, The Times wrote, “…on the top was a spray of flowers—carnations, chrysanthemums and gladioluses. More flowers were at each end of the coffin.”

Having known Johnson since he was a kid, Rev. William Bynes of the Bethel Church of God in Christ preached over the funeral. He later told a reporter, “I could only talk about him in generalities, you know. When he got above the teen‐age, he was not around us.” Outside of the chapel of the funeral home…a few black policemen in civilian clothes and one in uniform stood near the door. ‘To make sure there are no disturbances,’ one of them said when asked why they were there.”

There were a 100 people in attendance, though the funeral director thought there would be more. “A 29‐car procession led by a New Brunswick police car went to Franklin Memorial Park, in North Brunswick, for the burial,” The Times reported. “The coffin was not lowered into the grave while the mourners were present.” In a story published earlier that week, the paper had acquired a bank statement from the National Bank of New Jersey in New Brunswick that indicated that in January of that year the dead man’s balance was $2.05. On Saturday, July 3, 1971, the day of Jerome Johnson’s funeral, it might’ve been less than that.