I love the 1920s. I love the decade’s wild, willful, sensuality, its relentless search for modernity, its ecstatic embrace of political and social change and how it channelled war trauma into incessant partying. I love watching movies about the 1920s, I love dressing up in flapper garb and doing the Charleston and of course, I love reading about the decade (and the 1930s, and the wars that bookended the decades, the entire period.) In fact, if it wasn’t for my obsessive reading about the 1920s then I would never have written my first novel, April in Paris, 1921. What I love about crime novels from in and about this decade (and, to be honest, about crime novels in general) is the way they can address the daily consequences of political and social change. In this decade, it means books react to World War One, aka the Great War, and its long emotional aftermath. They react to the rapidly changing political scene in Europe, with the establishment of Communism in Russia and the rise of Fascism in Germany and Italy. They can address daily preoccupations with the changing—and therefore unstable—place of women, the working class, and race relations. Novels of the period define the genre and show the mechanisms of the mystery. Contemporary novels written about the period explore our current preoccupations through their counterpoints in the past. It makes for compulsive reading.

Here is a very brief, extremely brief, read-it-on-your-morning-commute brief selection of crime novels from or about the 1920s. I’ve divided them into two sections—the Masters, who wrote at the time and set the tone, and the Modern Masters, who’ve carried on their tradition.

__________________________________

The Masters

__________________________________

The British Master: Agatha Christie

Christie is the best-selling novelist of all time. Her play, The Mousetrap, has been playing in London continuously since it opened in 1952. Her two detectives, Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, have delighted readers—and viewers—for almost a century. If you want to know how to write a mystery, Christie is the woman to show you how. Christie has the best plots. Poirot is the detective of her 1920s publications. A former chief of police, he arrives in London as a Belgian refugee from World War One. In order to solve his mysteries, not only does he have a deep knowledge of how people of his time behave, but of the political and social forces that make them behave so. People’s attitudes to money, sex, and social position are different to now, so Poirot’s always-correct analysis is also a great analysis of the time the book was written.

The American Master: Dashiell Hammett

He is the Noah of noir, the cook of hard-boiled, the prince of the pared-back sentence. Hammett wrote the book on noir detective fiction (literally) that all others operating up and down the Californian coast have copied and built upon, from the lyrical brilliance of Raymond Chandler to the postmodern staccato of James Ellroy. Hammett’s Continental Op works in and around San Francisco during the 1920s, a time when California seemed to have only just shaken off the gold dust for the glitter of Hollywood. The Continental Op is almost brutal in the way that he seems to disappear into the mystery; his thoughts and feelings are nobody’s business but his, and that includes the reader. The puzzle, and how it talks about the political and social milieu of 1920s California, is everything. The one I read most recently had a rich young woman abducted by a cult, drugged, and framed for murder—a true window into the past.

Dorothy L. Sayers

Sayers is a wonderful writer, of detective fiction and everything else she put her pen to. Along with Christie, she created the British version of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction (along with Ngaio Marsh and Margery Allingham). Unlike Christie’s Poirot, Sayers’ hero Lord Peter Wimsey is an amateur detective, who she described as being part Fred Astaire and part Bertie Wooster (from the novels by P G Wodehouse)—a whimsical counterpoint to the serious Poirot and the serious content of her mysteries. Sayers was more explicit in her reaction to the political climate of her time, including Great War veterans, advertising, and feminism in her plots. But it’s Wimsey and his relationship with Harriet Vane, and the way she writes, that has kept readers coming back for more.

Margery Allingham

Margery Allingham wrote more than detective fiction, like Sayers, but was chiefly known for her detective, Albert Campion, introduced to readers in 1929. Campion is aristocratic and eventually works for British intelligence. His class and his career meant he can span the full spectrum of British society, from the almost-Royals to the shady slum-dwellers. The series progresses through his life and addresses the issues of the time—through World War two, Campion is with MI6, the same branch of the secret service as James Bond, but in the late 1920s the locked-room mystery spoke of class tensions and cultural preoccupations with ancient history and the occult.

John Buchan

Buchan makes his way here for the two Richard Hannay novels that were published in the 1920s—The Three Hostages and The Courts of the Morning. In 1915, Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps was a hugely successful spy novel and a favorite of soldiers at the front. Hannay is essentially an amateur spy, and one with a strong imperialist mindset, not unlike that of his creator. This is why this book is so interesting—it shows the mores and morals of 19th century colonizers in a post-WWI setting. In spy novels, politics is everything, and as Buchan also became Governor-General of Canada and worked for British Military Intelligence, his books are a good example of old-school political thinking.

__________________________________

A Brief Sidebar

__________________________________

I also wanted to include two writers of the 1930s here: Ngaio Marsh and George Simenon.

Ngaio Marsh was a New Zealander who wrote in and from 1930s London. Her gentlemen detective Roderick Alleyn works for the London Metropolitan Police (“the Met”) Marsh’s stories are short but great little puzzles, perfectly tightly structured and wryly funny. As Alleyn is a policeman, then the cross-section of politics and social mores that occurs around a crime scene is the focus of the mystery.

__________________________________

Read Ngaio Marsh: A Crime Reader’s Guide to the Classics on CrimeReads

__________________________________

George Simenon is a Belgian Master. He moved to Paris in 1922 and his detective, Maigret, knows the back alleys of Paris as well as his bohemian author. Maigret is a police commissioner and features in 75 novels (Simenon was prolific; he wrote 200 novels plus stories and more). The style is tough and clear-eyed, and gives a very different portrait of the interwar Europe to the novels of Christie and company – one sleazier, dirtier and altogether more French. They have recently been reissued by Penguin.

__________________________________

The Modern Masters

__________________________________

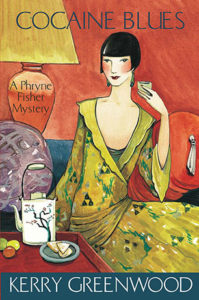

Kerry Greenwood: The Phryne Fisher books

The Honourable Miss Phryne Fisher is a brilliant creation. Tough, beautiful, smart, and wealthy, she loves all the sensual pleasures of life and pursues them without an ounce of guilt – all in-between solving numerous murders. Set in Melbourne, Australia, in the late 1920s, they’re a delicious picture of the type of city Melbourne was becoming after the Great War. Greenwood is explicit about the history of Melbourne, making the changing social milieu the catalyst for many of Phryne’s mysteries. The writing is lots of fun too; in fact, everything about Phryne is fun, from her naughty sex scenes, the luscious descriptions of food and clothes, the period voices—she was, and remains, and inspiration for my heroine, Kiki Button.

Volker Kutscher: The Babylon Berlin series

I found out about Kutscher from the Netflix series Babylon Berlin. The series is named after his first book, which is set in Berlin in 1929. This is a city hounded by change—the end of the war reduced the population to tatters, hyperinflation of the Weimar years and reparations reduced many to ever-worsening poverty, and in 1929 the fascists were lining up to seize power. Berlin is the place where the powerful come to play and the playful indulge in cocaine and kidnapping. Detective Gereon Rath is transferred to Berlin after he accidentally shoots a man dead in his hometown of Cologne. He’s a stranger in a strange city and he takes the reader on a wild ride through the sleaziest and sexiest parts of the city.

Jacqueline Winspear: The Maisie Dobbs series

Jacqueline Winspear explicitly addresses the long aftermath of World War One in her Maisie Dobbs series, set in London at the end of the 1920s and early 1930s. Dobbs was a nurse during the war, lost her beloved, and returns to England to study at Cambridge. She’s a working class girl who, through luck and high intelligence, works with a Poirot-type of investigator to become a professional investigator herself. Everything Dobbs does is in relation to the war which, even in 1929, still feels alarmingly close to all the characters. The mysteries, too, constantly speak about the way in which people feel alien in their own lives, cast adrift by the war’s catastrophe. Dobbs is thorough and determined and the style suits the character; I’ve read several.

Nicola Upson: The Josephine Tey series

This is set in 1930s London, so doesn’t really belong here, but I enjoyed the metafictional aspects of the series. Upson’s main character and amateur detective is Josephine Tey, the real detective writer of the 1930s. A crime writer writing about a crime writer who solves crimes—too delicious, as are the descriptions of sophisticated 1930s London, especially its theatre scene (both the fictional and real Tey are playwrights) and the fraught almost-romance with the handsome Roland.

***

This is such a small selection, so please tell me – which are your favorites? My shelves are bulging but I always need more books. Let me know!