You’ve got your large Coca-Cola in the cupholder affixed to the chair and your bucket of popcorn overflows into your lap. The lights go down and the movie begins. Cue the hero: some grizzled ex-special forces vet or former assassin with an ax to grind. This isn’t just any hero, though. This person is godlike, superhuman, the best in their field. No punch or kick will derail them. Maybe they’ll break a rib or two, or take a knife to the arm, but they will not stop kicking ass. Similarly, no bullet will take them down. There will be hundreds of bullets—thousands—fired at them over the course of the movie, and not one of them, not a single one, will be lethal. The bullets that do hit always find some noncritical part of the body: our hero’s shoulder, perhaps, or the three or four inches of expendable tissue between their ribcage and pelvis. Maybe they’ll cauterize the wound with something and carry on. And they have to carry on, because there are more bad guys to eliminate in a variety of spectacular ways. They are all around, flocking through the doors, through the windows, and our favorite badass is about to take them all out. Every last one of them. We watch with wide eyes, clawing popcorn into our mouths, totally absorbed. This is why we go to the movies—to be thrilled, to be entertained. It doesn’t matter that what we are watching is unrealistic, completely over-the-top fantasy action. We know exactly what we are going to get—a one-person-army—and we are all in.

John Wick is a great and extremely popular example of this action hero—the poster child for the one-person-army subgenre, although audiences have long been captivated by this explosive brand of cinema. I remember, as a kid, watching Max Rockatansky bring carnage to the parched Australian wildlands in Mad Max, and Bruce Lee going to a rival martial arts school and laying a beatdown on an entire dojo full of students in Fists of Fury. Kick after kick, punch after punch, Bruce dropped them to the mat (and usually, one punch or kick was all it took). I watched with huge eyes, thinking, I want to be that guy, I want to kick ass like that. My twelve-year-old mind was enthralled by the idea of taking those kung fu skills to school with me, and putting a hurt on all the bullies (and teachers) that caused me grief on a daily basis.

Which is, of course, a big part of what these movies offer us: a vicarious thrill. We can’t be that badass hero, because he or she doesn’t exist in the real world. But in the movies, we can shoot and kick alongside them for a couple of hours, albeit while shoveling popcorn into our mouths.

There are badass heroes in fiction, of course—Jason Bourne, Jane Hawk, Jack Reacher, to name just a few—and all pack a vicarious and entertaining punch. As a reader, I respond to these with great enthusiasm. As a novelist, I am interested in chaos, and the challenge it offers, and have always wanted to bring movie-level, balls-to-the-wall action into the pages of a novel. (Someone once told me that you should avoid writing car chases in fiction, so I put two in The Forgotten Girl.) Such ambition is perhaps imprudent, given that contemporary fiction and cinema—while both seeking to entertain—are governed by different rules. A thriller novel needs to be grounded in reality, whereas many action movies are encouraged to wallow in the outrageous.

Take Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill for instance. Our avenging hero, Beatrix Kiddo, arrives at the House of Blue Leaves with one job: to eliminate O-Ren Ishii, the queen of the Tokyo crime council. It’s a great setup—the plot has been established and the stakes couldn’t be higher—and it could work beautifully in a novel. But as soon as Beatrix disposes of O-Ren’s personal army (the Crazy 88), Tarantino puts his foot on the cinematic gas. He ups the ante, bringing in reinforcements, not just a handful of Yakuza henchmen, but dozens of them. They rush the House of Blue Leaves and completely surround our hero, dressed in identical black suits and brandishing lethal katanas. What follows is cinematic ballet—a visually poetic bloodbath—as Beatrix kicks, stabs, and slashes her way through the entire room. It’s stylistic, brilliant, and completely over-the-top. It does nothing to advance the character, however, or the plot. This is Tarantino indulging in his Japanese movie influences, and having one hell of a lot of fun in the process.

As chaotic and appealing as this style of action is, it’s really not workable in contemporary fiction—not to the same extent. The connection between a reader and a novel is cerebral, and a modern thriller needs to exist in a world with boundaries. The moment the author veers away from what is plausible, he or she risks losing the reader.

There are also issues in regard to repetition and flow. Think about John Wick and how many times he pulls the trigger over the course of the first movie (the answer is 153, by the way). How would that look on the page? You can tell and not show to a limited degree, but really, how many variations of, “he pulled the trigger,” can the author come up with before the reader wants to take a gun to the book herself?

Knowing this, I still felt impelled to rise to the challenge, and to answer a question that could tie me in literary knots: How do you take the daft square bullet of a Hollywood movie, and fire it down the smooth round barrel of fiction’s pistol?

Ultimately (and unsurprisingly), the answer is not in the bullets—whatever shape they may be—or in the action, but in emotion the author elicits in the reader. And from here the landscape looks more familiar. It’s one of characterization and plot. The former has always been something I work hard at, and take seriously—to create strong, believable personalities, for them to breathe on the page and to feel like true companions to the reader. Having characters that are robust enough to bear the weight of the story gives the author room to flex their muscle in other areas. They can stretch the bounds of reality just a little. They can chamber a few of those unwieldy square bullets.

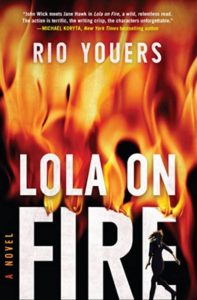

My new novel, Lola on Fire, is about a former mafia enforcer—a total badass—who is lured out of hiding by the mob boss she tried to kill 26 years before. She’s obviously older, and slower, her reactions aren’t what they used to be, she’s not as strong, and she has to overcome these physical and emotional obstacles if she hopes to not only save herself, but save her family, too.

This is the setup, and it lends itself to explosive, Hollywood-style action. Indeed, every review so far has commented on the book’s pacing and nonstop action, and New York Times bestselling authors have drawn comparisons to John Wick, Jane Hawk, Killing Eve, Elmore Leonard, Lisa Gardner, and Kill Bill. I’m obviously humbled by this (“Mission accomplished,” you might say), but it’s the characters that do most of the heavy lifting. It’s the emotions the reader experiences that lend the action scenes credibility, and make the novel work.

There are scores of fantastic action novels out there, and a dauntless army of fictional badasses. I salute them all, and thank their authors for raising the bar. I tried to do something a little different with Lola on Fire, though. This was my attempt to bring cinema’s brazen, full-throttle action style into the pages of a book. Yes, the cover is wrapped in flames and the body count begins on page one, but beneath all of this—beneath the flamethrowers, the .45s, and the entry wounds—are the fundamentals of storytelling.

Make no mistake, Lola on Fire is a novel, through and through.

Even so, bring your popcorn.

*